While the Fed dithers over whether preventing job losses or hotter inflation should receive more attention, it may get help from an unexpected source. The Supreme Court is currently hearing arguments over the legality of the Trump administration’s tariff blitz, having to decide whether it is justified by the International Emergency Economic Powers Act. If it upholds lower court rulings that it is not, there is a real chance that about $90 billion of the roughly $200 billion of tariffs collected this year will be returned to companies that had to pony up the levies. No doubt, if SCOTUS rules against the administration, President Trump will vigorously pursue other legal avenues to keep the revenues on the books, and he may well meet with some success.

At the very least things will get messy and generate a trail of heightened uncertainty into an already volatile tariff landscape. However, the direction of travel would change. Until now, the uncertainty created by the chaotic pattern of tariff announcements focused on whether the outcome would be a one-time boost to the price level after all trade agreements were in place, or whether President Trump would find reasons to impose additional tariffs down the road, resulting in a series of increments that drives up the inflation rate. However, an adverse ruling by SCOTUS could change the compass, reversing the cost-inflating influence that is fueling higher prices.

To be sure, if that were to occur, there could be a wide range of outcomes. The most desirable from a macro perspective — and for consumer wallets — would be that businesses decide to return the funds to the public, lowering prices by the amount they were raised due to tariffs. That would be a win-win for the records, ushering in a temporary bout of deflation without causing damage to the economy. Keep in mind that deflation is usually viewed as anathema by economists. It discourages people from spending because they expect prices to go even lower. When that becomes contagious and aggregate demand collapses, businesses lay off workers and curtail investment spending. That, in turn, feeds a self-reinforcing cycle, known as a deflationary spiral, a condition that is difficult to stop and is associated with steep downturns. None of those negative impulses would surface in this case.

Such a benign outcome, however, would compete with other ways that companies could use the returned tariff revenues. The path of least resistance is that they just replenish their coffers, boosting balance sheets and, perhaps, lifting stock prices. However, the tariff refunds would also reduce government revenues, resulting in more Treasury borrowing and higher market yields that could offset the positive wealth effect on spending from stock market gains. Still, this option removes the tariff-linked cost pressure to raise prices, providing a modest check on inflation.

Alternatively, companies could use the tariff refunds to boost investment spending and/or keep more workers on payrolls. This option would be the least favorable for inflation as it imparts more vigor into aggregate demand, enhancing the economy’s ability to accommodate higher prices. But to the extent the funds are used to bolster investment spending, it would also lead to productivity gains that are a time-honored curb on inflation. From the Fed’s perspective, a ruling by SCOTUS that would diminish the influence of tariffs on inflation would allow it to focus on the forces impacting jobs and inflation that it can control, reducing the risk of a policy error.

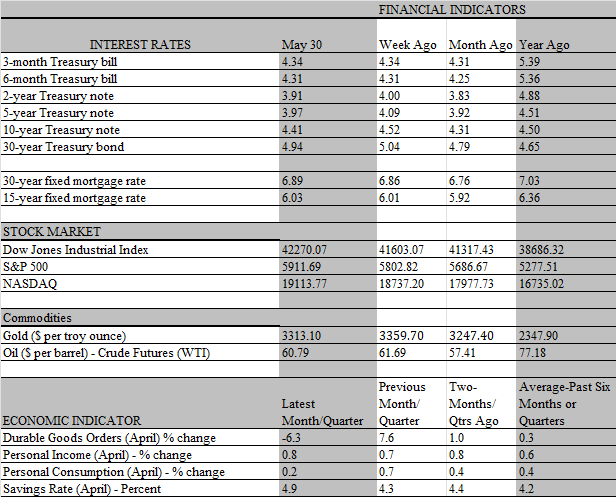

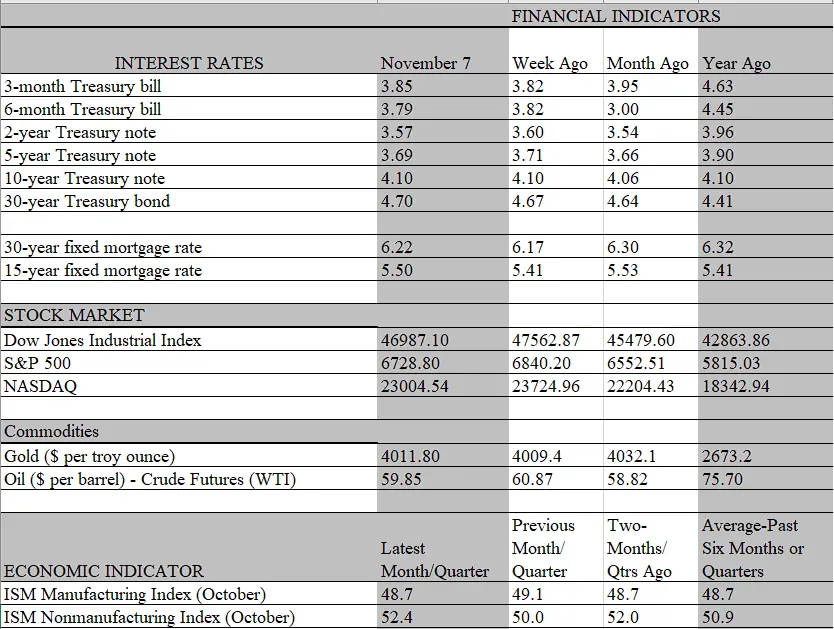

That said, it will be at least several weeks before a court ruling is made, and the government shutdown is providing more than enough uncertainty for the Fed to deal with. In the absence of official data on jobs and inflation heading into the policy meeting next month, the Fed – like the rest of us – is relying more on private sources for guidance on the economy’s performance. The mix of information available tells us more about consumer behavior and labor conditions than inflation. Still, the downbeat mood on Main Street captured in surveys continues to be heavily influenced by high prices, which are eating into incomes and putting ever-more stress on the budgets of low and middle-income households. The University of Michigan consumer sentiment index, released on Friday, fell to the lowest level in more than three years in early November, just a tad above the record low hit during the peak of the inflation spiral in June 2022.

To be sure, the government shutdown was the biggest drag on the index, as households mentioned it more frequently than any other dispiriting event in the survey. We expect that sentiment slump to be reversed when the government reopens, furloughed workers receive their back pay and the threat of spillover effects on the broader economy from the shutdown recedes. Importantly, the link between consumer sentiment and behavior has weakened in recent years, so the Fed will be more focused on what households do rather than what they say. At this juncture, there is little evidence that they are going into hibernation. Spending is holding up, thanks mainly to the profligacy of upper income households whose appreciating equity portfolios has, until this week, provided critical support to purchases. However, the market jitters stoked by the government shutdown this week is a reminder of the economy’s vulnerability to a negative wealth effect.

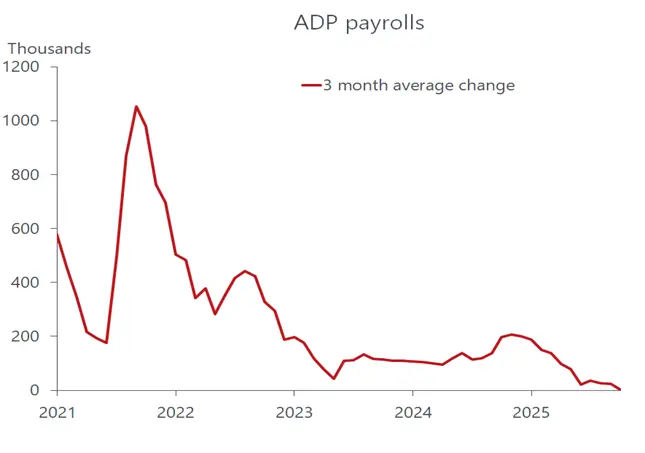

The biggest unknown centers on the job market, where conflicting evidence continues to prevail. By all accounts, the low hiring/low firing narrative in effect for several months has not been upended. Some private sources, notably Challenger, Gray & Christmas, revealed a startling increase in layoff announcements last month, but that reading is not confirmed elsewhere. State unemployment offices continue to report a relatively low level of initial claims for unemployment benefits. But while employers are holding on to workers, they are also not adding to staff, as hiring has slowed to a crawl. That was evident in the official payroll data before the government shutdown and confirmed by more recent data provided by the payroll processing firm, ADP. It is interesting to note, however, that while the headline-grabbing layoff announcements may not be nudging overall unemployment higher, they are occurring mainly in white-collar industries. This raises the question of how much longer high-income earners can do the heavy lifting of driving the economy.