The latest spate of Fed speakers did little to squelch market concerns that interest rates would be held at elevated levels for the foreseeable future. Indeed, market sentiment of late is that the long-awaited cuts will be pushed back even further than thought a few weeks ago. Stubborn inflation amid a still muscular- though modestly slowing- economy continues to be the key hurdle blocking the initial move. Recent economic reports, including this week’s batch of data, provided no reason for traders to change their view. A common theme underscoring the Fed’s persistence in keeping rates steady is that they have yet to materially tame the drivers of inflation. Consumers are still spending, the job market continues to chug along and even residential construction, historically the most rate-sensitive sector of the economy, is booming. While price increases are slowing, punctuated by Friday’s mildly encouraging report on the PCE deflator for April, they are doing so far too gradually for the Fed’s comfort. What’s more, the public still frets more over the high level of prices relative to three years ago than the slower monthly inflation rate over the past year.

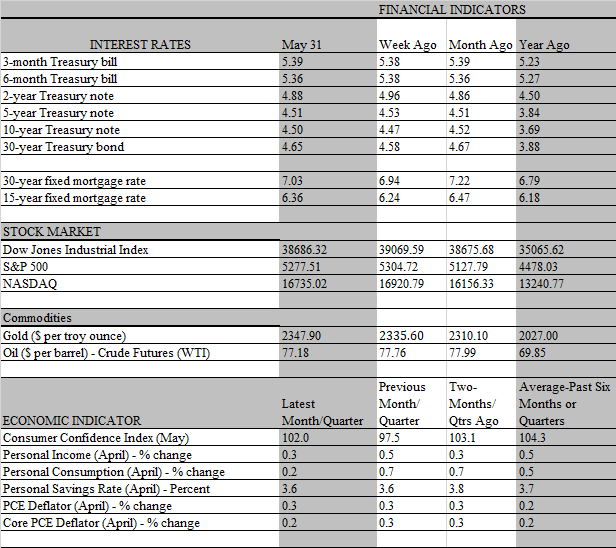

Several explanations have been given as to why the Fed’s steep rate hikes have not had more of an impact on economic activity. The most notable is that the economy has a cushion of protection from the low-rate environment that prevailed for decades prior to the rate-hiking campaign. That allowed households and business to lock in low borrowing costs, which insulates them from the current higher level of rates. The poster child among the beneficiaries is the homeowner that obtained a 30-year mortgage at a fixed rate that is less than half the roughly 7 percent a borrower would currently pay to finance a home purchase. Not only is the higher prevailing rate irrelevant for millions of homeowners that locked in a lower rate and plan to stay put, but the vast appreciation in home values in recent years imparted a big jolt into their net worth.

To be sure, this is not a win-win for all concerned. These very homeowners may also be locked out of selling their homes and trading up to new ones, as the transaction would involve giving up their low-rate mortgage. That, in turn, limits the supply of homes for sale — a real problem in the existing housing market — which sustains upward pressure on home prices and reinforces the affordability problem that shuts first-time homebuyers out of the market. Still, the current high level of mortgage rates does not impair the spending capacity of homeowners. Indeed, the wealth boost from appreciating housing equity may well encourage them to save less and spend more than otherwise. However, there is an offsetting – though indeterminate – drag on spending as erstwhile home buyers are forced into the rental market, driving up rents, which are taking an ever-increasing slice of lower-income household budgets.

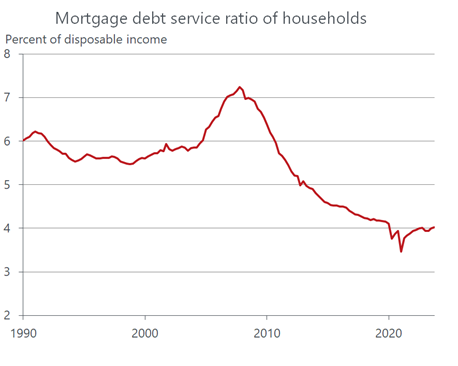

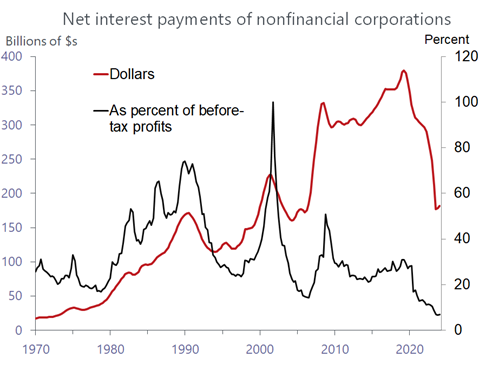

A similar insulating effect can be seen in the business sector, where corporations have either refinanced high-yielding debt or tapped into the capital markets for billions of new funds at rates significantly below current levels during the pre-pandemic years. Hence, despite the spike in short-term borrowing costs on bank loans and commercial paper over the past two years, debt servicing charges have not made a dent on corporate balance sheets. Indeed, interest payments by nonfinancial corporations are hovering near the lowest levels in nearly two decades. What’s more, you would have to go back to 1957 to find a lower fraction of before-tax profits taken by debt-servicing payments. According to the second estimate of GDP released this week, net interest payments in the first quarter are about one-half the level of a year earlier.

That said, the legacy of low rates has delayed, but not derailed, the full impact of the Fed’s tightening campaign. The lags may be longer, but higher rates are steadily taking some steam out of the economy’s growth engine and cooling the inflation embers. Households and businesses still rely on credit to spend, invest and to sustain operations, including financing payrolls. Moreover, the increasing use of credit cards by consumers is taking a toll on a broad swath of lower income households. Delinquency rates are climbing as this cohort is struggling to meet the skyrocketing rates on both credit cards and auto loans. The spillover effect on spending is muted by the still solid job market, which is sustaining wage growth. But here too, the trend is turning weaker.

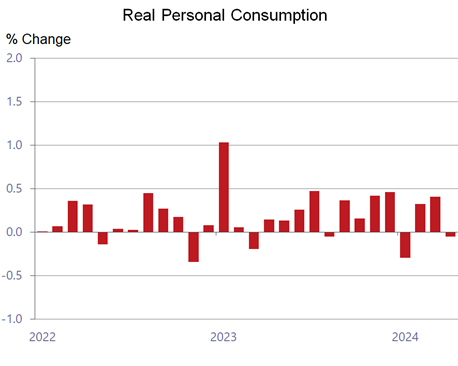

In April, income after taxes failed to keep up with inflation for the second time this year and is steadily losing ground. Over the past year, real disposable income has increased by just 1.0 percent, well below the 5.3 percent pace seen last summer, which stoked an above-trend 3.2 percent increase in real consumption over the second half of 2023. Unsurprisingly, the slowdown in real income growth is now pulling down spending growth. Real personal consumption slipped to a 2 percent growth rate in the first quarter. Importantly, the second quarter started on a weak footing, as real consumer spending fell by 0.1 percent. Admittedly, some of that weakness reflects a payback from the strength in March, as some spending, particularly for goods, was likely pulled forward by an early Easter holiday and a Prime Day sales event by Amazon.

But consumers are running on less fuel than earlier this year and much less than in 2023. For one, the savings rate is hovering near historic lows of 3.6 percent compared to a 4.5 percent average in 2023. As noted earlier, strong aggregate balance sheets underpinned by surging home prices and equity portfolios, likely encouraged households to save less than otherwise. But lower-income households have exhausted their savings and are living paycheck to paycheck; for them, sustaining wage growth is critical to their spending behavior going forward. The good news is that the job market remains solid, and layoffs are low, with most job losses apparently concentrated in the higher-paying tech sector. The bad news is that job openings are falling and wage as well as payroll growth is slowing.

We expect this trend to continue and set the stage for the Fed to start cutting rates before the end of the year. The main barrier would be stubborn inflation, but some encouraging signs appeared in Friday’s income and spending report that included the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge. As was the case with the earlier consumer price report, the personal consumption deflators for April did not come in hotter than expected, short-circuiting the upside surprises that occurred over the first three months of the year. The headline PCE deflator increased 2.8 percent from a year ago and the core inflation rate rose 2.7 percent, both unchanged from the previous month and both increases just as expected.

To be sure, the Fed’s 2 percent target is still a distance away and is not likely to be reached this year if only because rates over the second half of this year will be compared with slower inflation rates over the second half of 2023. However, further progress should become more visible in 2025 when housing costs -a major inflation driver- will be slowing appreciably. Keep in mind that the Fed will not wait for inflation to hit 2 percent to start cutting rates, only that it is moving sustainably towards that target. That trend, combined with a softening economy, should become apparent over the second half of this year.