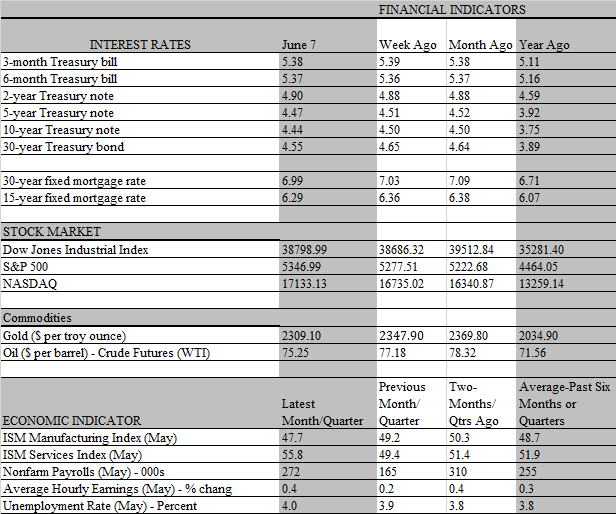

Friday’s robust monthly employment report silenced a nascent whisper campaign that a July rate cut by the Fed was on the table. That notion was spurred by a string of incoming data revealing a softening job market, cooling inflation, and signs of slower growth in the broader economy, underpinned by a pullback in consumer spending. While those trends have not been upended, in our view, the stronger than expected job growth in May is an upside surprise that should defuse any dovish sentiment that might have appeared at next week’s FOMC meeting. Indeed, the fraction of hawkish Fed officials who believe that policy is not restrictive enough may well be emboldened by the latest jobs report.

But while the data-dependent Fed is likely to stick with its “wait and see” stance, the latest jobs report is not expected to sway it to the more hawkish camp. Admittedly, the attention-getting headlines suggest that the labor market is on fire. Nonfarm payrolls surged by 272 thousand in May, about 100 thousand more than the markets expected and far stronger than the 165 thousand gain in April. More telling from an inflation perspective is that wage growth was also hotter than expected, as average hourly earnings increased 0.4 percent, the strongest since January’s 0.5 percent gain and double 0.2 percent increase in April. That increase lifted the gain over the past year to 4.1 percent from 4.0 percent in April. Robust hiring and reaccelerating wage increases is not a combination that would further the Fed’s conviction inflation is moving sustainably towards its 2 percent target.

That said, it would be a mistake to place too much emphasis on these headline data. For one, they run counter to other reports that, as noted above, depict slowing activity and cooler inflation. A true sense of the underlying trend will require more time and data on all fronts. Importantly, the Fed will receive a key inflation report just before the conclusion of next week’s policy-setting meeting, as the CPI data is due to come out on Tuesday. For another, the jobs report itself contains internal inconsistencies, including details that depict more weakness than strength. For example, the unemployment rate inched up from 3.9 percent to 4 percent, breaking a string of 27 consecutive months in which it stayed below that threshold, the longest since the 1960s.

That increase, in turn, was derived from the household survey that revealed a whopping 404 thousand plunge in employment last month. To be sure, the sample size in the household survey is much smaller than in the establishment survey, which generates the headline payroll data considered to be a more accurate measure of labor market conditions. However, over time the two measures should align more closely whereas that has not been the case this time. Over the past year, employment in the establishment survey has increased by 2.7 million, including the 272 thousand increase in May. By contrast, employment in the household survey grew by a much smaller 400 thousand over the past twelve months, including the 404 thousand drop last month. Again, the payroll increase more accurately reflects labor market conditions, but the extent and length of time the household survey has underperformed sends a cautionary signal that things may not be as robust as they seem.

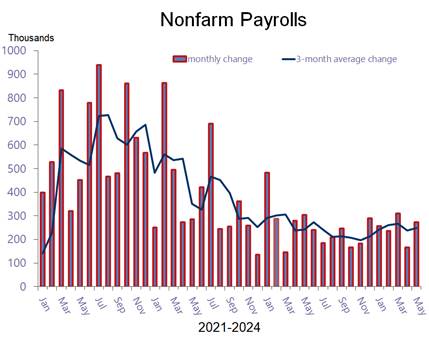

A key reason the torrid job growth last year did not prevent wage growth from slowing is that the supply of workers also expanded considerably, matching demand. In May, however, the labor force participation rate fell back to 62.5 percent from 62.7 percent in April. But the decline was entirely among older workers, those 55 and up. Their participation fell for the second consecutive month, to 38.2 percent from 38.4 percent in April and 38.6 percent in March. Indeed, you would have to go back to August 2006 to find a lower participation rate among seniors.

It’s unclear if this represents the start of another wave of early retirements, and if so, why? If the exodus of older workers from the labor force is a sign of reduced demand for their services, reflecting perhaps cost cutting measures by employers, that would be a sign of weakness. Alternatively, if the older cohort is leaving the labor force voluntarily because of improved finances, that would suggest strength. Keep in mind that retirement plans have enjoyed a major boost from the powerful stock market rally last year, which continued into the early months of this year. What’s more, the runup of interest rates engineered by the Fed has delivered a nice boost to the income revenue received by bondholders, who are more likely to skew older.

Putting aside the issue of older workers, other details in the jobs report suggest a cooling trend. We are keeping an eye on the drop in temporary help, which has been considered a leading indicator for future job growth. Temporary help employment has fallen by 36,000 since the end of last year and is down by 453,000 from its recent peak. A good chunk of the weakness has been in transportation/warehousing. This could be attributed to a weakening in consumer spending on goods as well as businesses overstaffing during the boom in online spending. However, some temporary help positions have been turned into permanent positions, so we are not overly concerned yet.

Another sign of potential weakness is that unemployed workers are taking longer to find a job. The median duration of unemployment rose from 8.7 weeks to 8.9 weeks last month. The level is still historically low but merits watching as a steady climb in longer-term unemployment would at some point enter the mindset of employed workers, stoking job insecurity. That, in turn, would influence spending behavior and set in motion the forces that typically saps economic momentum. To be sure, we are a ways from that point. Despite the nagging details that dilute the headline strength in the latest jobs report, the overriding fact is that the economy is still generating a healthy number of jobs, unemployment remains historically low and, importantly, worker pay is rising. Depending on what we see in next week’s CPI report, the May increase in average hourly earnings indicates that wage growth continues to outpace inflation.

Hence, while the latest job numbers should not derail a Fed rate cut later this year, they do support the view that there is no rush for policy makers to make the move. We still expect inflation to cool in coming months alongside a loosening up of the job market, but the trend may not be convincing enough for Fed officials until the fall. The risk always is that the Fed waits too long before it starts unwinding the steep rate hikes it put into effect since the spring of 2022. But those hikes are proving less damaging than previously thought, and there’s a good chance that keeping rates higher for longer than the doves would prefer will not lead the economy into a recession.