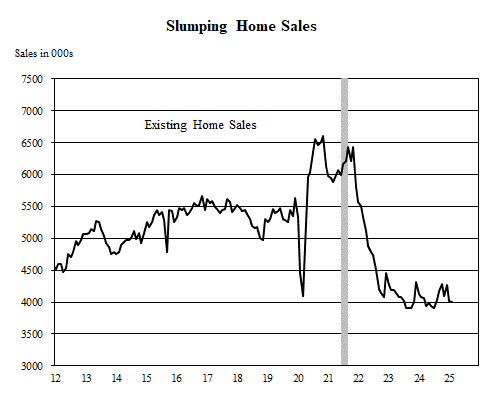

The highlight of the week once again came out of Washington, and this time it did not only involve tariffs. On Thursday, House Republicans narrowly passed a major reconciliation bill to deliver President Donald Trump’s economic agenda. However, it’s up to Senate Republicans to craft their own version, which will likely differ from the House bill on substantive issues. Hence, it is premature to judge just how fiscal policy will influence the economy in 2026 and beyond.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) is a sweeping piece of fiscal legislation, of which a large chunk is dedicated toward extending the expiring provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017. Such tax-cut extensions keep current fiscal policy settings stable, but what matters for financial markets and the real economy are the other potential changes to current tax and spending policy that ultimately comes out of Congress and is signed off by President Trump.

On paper, the OBBBA will reduce the deficit as soon as it’s passed, presumably in the current fiscal year. However, the reduction is mainly a statistical exercise rather than real savings. Simply put, it reflects the lifetime savings of proposed changes to student loans, which are recorded up front on a present-value basis. Lower student loan benefits under the OBBBA will affect the federal debt and the economy over a longer period by increasing monthly cash flows into the Treasury as borrowers make larger payments to the Education Department than would otherwise occur. But the actual savings will be spread out over years while the budget document will compress it into year one.

Take out the statistical legerdemain from changes to student loans and the OBBBA will provide a modest boost to growth early on. That support will only grow over the next few years as tax incentives for business investment, expansions of certain TCJA provisions, and tax proposals from the 2024 presidential campaign take full effect. The budgetary savings from cuts to Medicaid and SNAP and recissions of the Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) clean energy policies work in the opposite direction, but the OBBBA supports the economy through fiscal year 2028, when many of the tax changes expire.

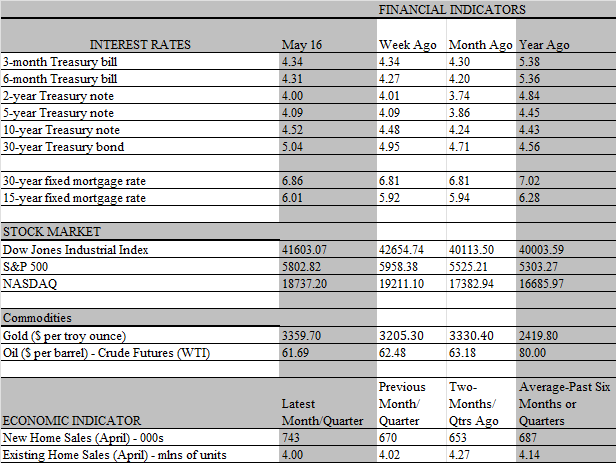

Once President Trump’s second term ends, the net fiscal impulse from the House bill turns decidedly negative. At that time, the tax cuts expire, and the spending increases on defense and border security begin to unwind, all while the cost savings squeezed from social benefit programs and the IRA remain in place. The bill will add trillions to the national debt and that prospect is already unnerving the financial markets, where the 30-year treasury yield staged an unusually big upward move this week. To be sure, other influences played a role, including soft demand for the Treasury’s 20-year bond auction this week and the lingering inflationary implications from tariffs.

Speaking of which, it appears that the good vibes associated with the de-escalation of trade tensions may be waning. On Friday, news that President Trump is once again ramping up the tariff threats, announcing a 50% tariff rate on the EU beginning June 1 and 25% on imported I Phones as part of a campaign to get Apple to manufacture the phones in the U.S. The news did little to calm the nerves of investors, and stock prices ended the week on a down note. We will see where this goes when the markets reopen following the three-day respite provided by the Memorial Day holiday.

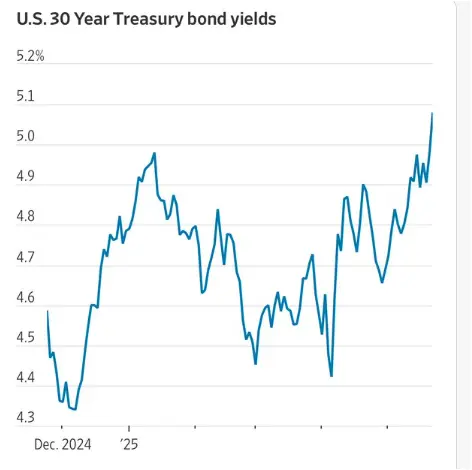

As it is, the combination of surging budget deficits and a resumption of tariff threats can only be bad news for interest rates, which, as noted, have already moved significantly higher over the past month. This poses the biggest threat to the housing sector, which is highly sensitive to financial conditions. Mortgage rates are heavily influenced by changes in the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield and are poised to hit 7 percent on 30-year mortgages for the first time since January if the recent moves in Treasuries hold. The rate climbed to 6.86 percent this week according to Freddie Mac.

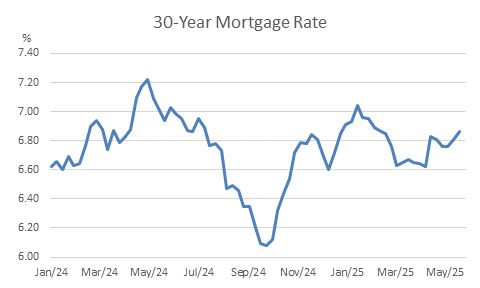

Unsurprisingly, the increase in mortgage rates has arrested the modest recovery in home sales that took place over the second half of last year in response to the sharp decline in rates that occurred earlier in the year. In April, sales of existing homes which account for the lion’s share of home sales slipped a half-percent to an annual rate of 4 million units. Keep in mind that these sales reflect contracts that were signed back in February and March when mortgage rates were lower than they are now.

Indeed, the slippage in April’s sales is an ominous sign as the spring sales season gets underway. Not only was it 2 percent below the year-earlier level, but it was also the weakest sales pace for the month of April since 2009 amid an historic meltdown in the housing market. And while existing home sales do not directly affect GDP (since they represent a transfer of assets), they do indirectly. That’s because the purchase of goods and services linked to a sale i.e. furniture, appliances, carpeting, renovations, moving expenses are integral components of personal consumption that is the economy’s main growth driver. Keep in mind too that a slumping housing activity is a time-honored leading indicator of recessions. All the more reason to keep an eye on interest rates and whether a yippy bond market will once again cause President Trump to retract his latest tariff threats.