It’s been a while since the hard economic and inflation data delivered unequivocal good news for traders and investors. True, one might quibble as to whether a spike in applications for jobless benefits qualifies as “good news”. But for a Federal Reserve that has been on a long quest to tame inflation without causing a severe disruption in the job market, the modest lengthening of the unemployment lines hardly qualifies as a discordant note. Besides, there is reason to suspect the one-week reading as it comes right after the Memorial Day holiday, which can lead to noisy data. Even if the higher level of first-time claims is genuine, it is still lower than last year’s total and comfortably below the break-even level where layoffs would exceed hiring, resulting in a drop in aggregate employment.

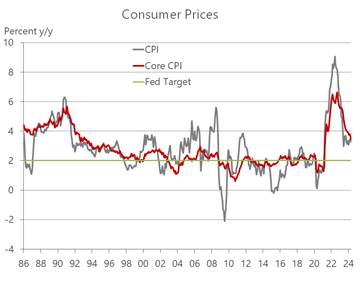

While softer labor market conditions are a positive omen of easing wage and price pressures, the immediate inflation landscape also took a turn for the better. The widely followed monthly report on consumer prices revealed a slower pace of inflation last month than expected, a welcome respite from the upside surprises in previous months. The tamer price increases quelled, at least for now, the heightened concern that inflation was reaccelerating following the encouraging retreat last year. It’s premature to say that the hotter inflation readings earlier this year was nothing more than a bump in the road to the Fed’s 2 percent target. But the downside surprise was enough to stifle the inflation-driven climb in market interest rates stoked by the stronger-than-expected jobs report last week.

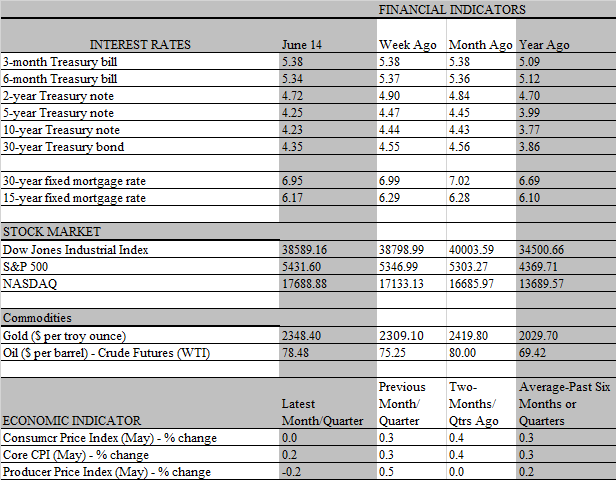

Indeed, the 10-year Treasury yield completed a round trip journey since that release, erasing all of the increase and then some. As of this writing on Friday, the yield sits at the lowest level since late March when hawkish comments from Fed officials sent market rates surging. The policy-sensitive 2-year Treasury yield has traveled a similar roller-coaster ride. Interestingly, while the FOMC meeting that concluded on March 20 set the stage for the subsequent rate climb, Fed officials still projected three rate cuts at the time. That median forecast was revised dramatically at this week’s policy meeting, as Fed officials penciled in only one reduction. Just as traders refused to believe the Fed’s previous rate forecast, responding more to the higher for longer narrative espoused by Fed Chair Powell at his post-meeting presser, they now believe that more than one rate cut is in the cards this year.

It’s no surprise that the benign inflation reading this week failed to coax the Fed into a more dovish posture. As Chair Powell reiterated in the post-meeting press conference, the CPI report was a step in the right direction, but more than one month’s data is needed to convince the Fed that inflation is moving sustainably towards the 2 percent target. To be fair, it was a close call at the meeting regarding rate projections. Of the 19 members of the committee, four penciled in no cuts at all this year, eight expected one reduction and seven anticipated two reductions. Hence, if one member switched sides to the two-cut camp, the median forecast would also have shifted to two rate reductions, and chatter about the Fed’s plans in the financial media might have sounded a more dovish tone.

From our lens, the prospect of two rate cuts beginning in September is very much in play. True, it would be a mistake to read too much into a single CPI report. But for a change, the headlines and most of the underlining details aligned to portray a broadly based easing of price pressures. The headline CPI was unchanged for the month, thanks in large part to a drag from declining gasoline prices, but the more influential story came from the slower rise in the core CPI, which excludes volatile food and energy prices and is a more accurate measure of inflation trends. The 0.2 percent advance in the core index was the weakest monthly change since August 2021 and lowered the increase over the past year from 3.6 percent to 3.4 percent, the slowest annual gain since April 2021.

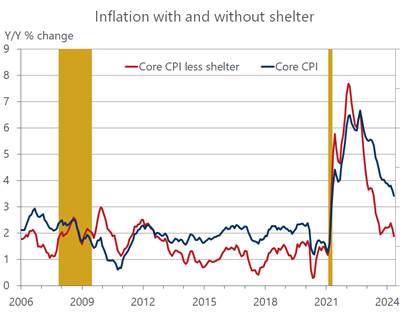

Encouragingly, the super core measure -core service prices excluding shelter- that the Fed is closely monitoring because it is linked to labor costs and cyclical forces fell in May for the first time since September 2021. The -.04 percent drop is barely noticeable, but it contrasts sharply with 0.6 percent average increase over the previous four months. Still, this measure is running 4.7 percent above year-earlier levels so the Fed would need to see more improvement in coming months. What’s more, the main sticky price that is preventing a faster decline in overall inflation showed little improvement last month. Shelter costs rose 0.4 percent for the fourth consecutive month in May and are up 5.4 percent over the past year. The influence of this component on inflation cannot be underestimated; take shelter out of the calculation, and core CPI is up only 1.9 percent from a year ago. The good news is that the slower rent increases on new leases should soon start to feed into the housing component and reinforce other influences that will speed up the disinflationary trend.

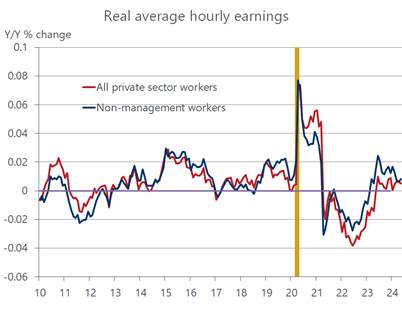

One key influence is the cost of labor, which, like broader inflation measures, has only grudgingly decelerated. But that too may be on the cusp of speeding up, particularly if the job market shows more signs of cooling. As noted earlier, jobless claims are rising, punctuated by a spike in the first week of June that lifted total first-time applications for jobless benefits to the highest level since last August. Odds are, the increase does not reflect a wave of layoffs by employers, which is not supported by other data, nor would it offset the increase in hiring that is still running at a solid pace. More likely, it reflects the reduction of job openings being posted by companies, which is lengthening the time it takes for laid-off workers to find new positions, driving them to unemployment offices to claim benefits that tides them over.

What’s more a big chunk of the increase in claims came from California, which may be a one-time outlier. However, there could be a more substantive reason for the spike that bears watching. The minimum wage in California went up from $16 to $20 on April 1st, which spurred a number of fast-food restaurants to lay off workers and at least one major chain ” Rubio’s ” to file for chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, citing significant increases in labor costs as the reason. Other fast-food restaurants are lifting prices to cover the wage hike, but if customers rebel against the increases more workers could be scuttled. The silver lining is that wages rose faster than prices in May. Indeed, real average hourly earnings matched the strongest monthly increase in ten years, except for a brief two-month period during the teeth of the pandemic recession when low-wage workers were purged from payrolls, boosting the average wage. Importantly, with a nod to the minimum wage increase, low-wage workers are catching up; for the first time this year, real average hourly earnings of nonmanagement workers increased faster than for all private sector workers in May.

We expect the cooling of wage growth to continue in coming months amid a gradual easing of labor market conditions. And, while the benign consumer price report this week grabbed most of the headlines, it was followed by an equally tame reading on wholesale prices. Importantly, the components of both these reports that feed into the personal consumption deflator points to a slower rise in that Fed’s preferred inflation measure as well. The ingredients for a resumption of last years disinflationary trend are falling into place, which should become significant enough for the Fed to start lowering rates by late this summer or fall.