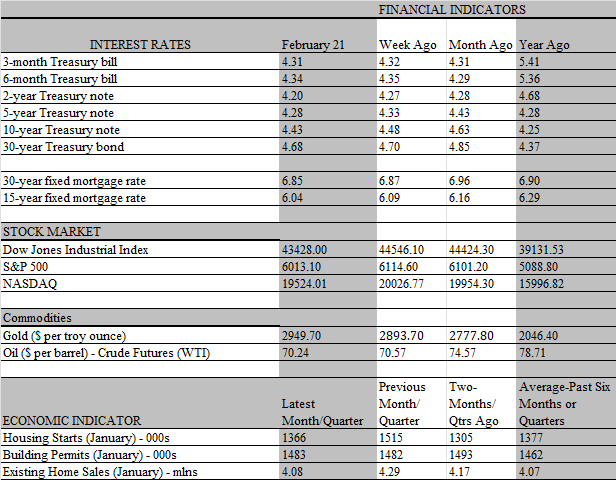

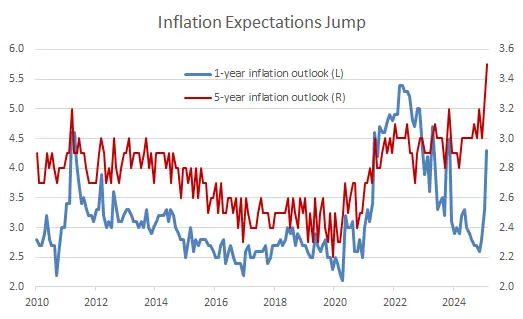

Amid a light calendar of economic data, uncertainty continued to escalate among investors and traders this week. The elephant in the markets, of course, is the topsy-turvy world of tariff threats by the Trump administration, which was further expanded this week to include lumber and encompass more trading partners under the tariff umbrella. It is still unclear what will be put into effect or used mainly as a negotiating tool to gain concessions from trading partners. So far, only the 10 percent tariffs on China have been implemented. But the prospect of an extensive rollout and a possible all-out trade war is infiltrating public sentiment; it remains to be seen if real changes in behavior will follow. One thing is clear there has been a meaningful uptick in inflationary expectations as well as a downbeat move in household sentiment regarding the economy and inflation.

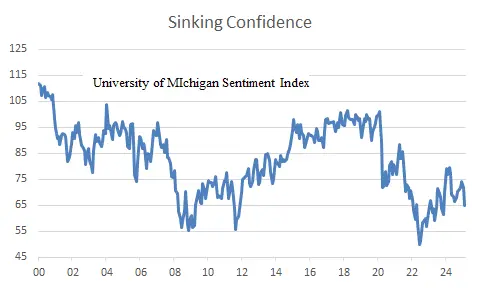

The latest evidence of the mood shift came from the University of Michigan on Friday, which released updated results of its February survey of households. The final consumer sentiment index was revised lower from its preliminary reading taken earlier in the month, declining to 64.7 from 67.8. This was more pessimistic than consensus expectations for the index to be unchanged and is down from its January reading of 71.1. The overall index is now lower than it was before the election.

Most notably, the drop in sentiment was driven by fears over the inflationary impacts of tariffs although higher fuel prices and a rockier performance in the equity markets also contributed. Details from the press release showed that the decline was pervasive, with sentiment falling across all age and income groups. However, the survey continued to retain a strong political bias as sentiment was unchanged for Republicans but lower for Democrats and Independents. That split reflects deeply rooted disagreements over the consequences of Trump’s economic policies.

Importantly, the final reading confirmed the massive jump in consumers’ inflation expectations this month. Consumers’ year-ahead inflation expectations shot up to 4.3% from 3.3%, reaching their highest level since November 2023 and leaving expectations significantly above the pre-pandemic range. Long-term inflation expectations also rose to 3.5% from 3.2%, their highest level in 30 years. Clearly consumers are becoming more concerned about the inflationary repercussions of tariffs after President Trump began making a slew of announcements this month, targeting China, Canada, Mexico, and an expanding list of various commodities.

The question is, will the seismic change in expectations have implications for the real economy? That, of course, is where the rubber meets the road and, again, will depend on what actually is implemented. From our lens, the overall impact on the broader economy should be relatively modest both for inflation and growth. For one, we believe that the scale of tariffs will ultimately be watered down, as concessions will be made through negotiations with trading partners. For another, consumers will not feel the full brunt of the tariffs, as businesses will absorb some of the costs. Hence, while there would be one-time upward adjustment in the price level from the tariffs, the overall inflation rate should not receive a significantly boost.

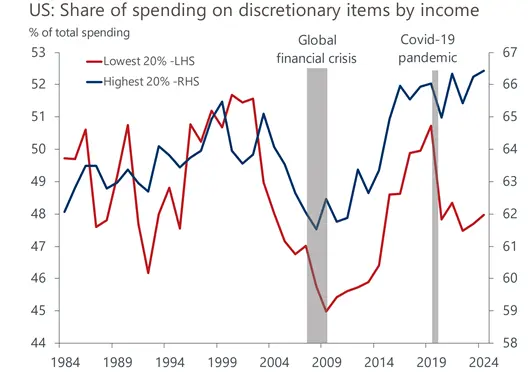

Likewise, higher tariffs assuming they are watered down from the aggressive levels being proposed should not make a meaningful dent in growth prospects. That’s because upper-middle and high-income households account for more than 90 percent of aggregate consumer spending, and this cohort of the population is fiscally equipped to handle modestly higher prices coming from tariffs. Their balance sheets are in healthy shape, thanks to the vast appreciation in stocks and home prices in recent years, as well as the solid growth in incomes from a robust job market. What’s more, they also have a sizeable savings cushion to tap into if their earnings lag the rising cost of items they normally buy, particularly for discretionary items.

However, lower-income households are likely to be more exposed to the impact of tariffs, partly because they spend a disproportionate share of their income on the goods most likely to be affected, but also because they have smaller savings buffers to withstand the hit to real incomes. Keep in mind too that they did not benefit as much from the gains in asset prices since the pandemic and their balance sheets are burdened with a sizeable increase in debt. Hence, beyond their macro impact on the economy, higher tariffs would widen the gulf between low- and upper-income households that has been opening up in recent years. One way to assess that gap is to look at the share of spending that each group devotes to discretionary goods and services.

As the chart shows, in the decade leading up to the pandemic, low-income households spent an increasing share of their purchases on discretionary items, a sign they were fully participating in the economic expansion of the period. However, during the post-pandemic recovery the share has dropped sharply for the lowest-income households, or those earning less than $30,000, whereas the highest-income households, or those earning more than $150,000, have continued to increase discretionary spending as a share of their total spending. To be sure, the aggressive rate hikes by the Federal Reserve in 2022 and 2023 played a key role in this development, as borrowing to finance big-ticket goods and services, such as cars and vacations, became prohibitively expensive for low-income households.

While the Fed provided some relief by lowering rates a full percentage point since September, it has now hit the pause button on the rate-cutting campaign and is not likely to resume cutting for the foreseeable future. That message was conveyed at the last policy meeting in January and validated by the minutes of that meeting released this week. In it, policy makers were united in the view that inflation was remaining stubbornly high; until it shows more evidence of slowing the wisest course of action is to remain on the sidelines. Importantly, some officials have begun to incorporate tariffs into their thinking about inflation. Like everyone else, however, they do not know how the plethora of tariff options will play out. Hence, as is the case in the private sector, the fog of uncertainty is throwing a wrench in the decision-making process at the Fed.