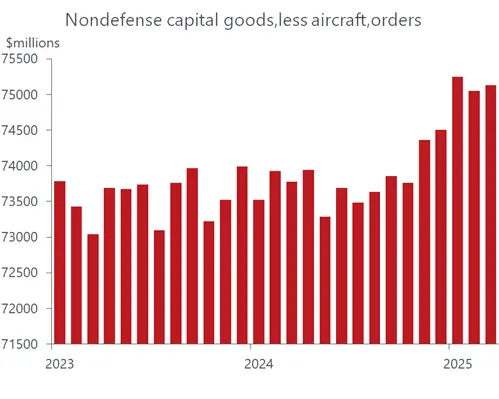

By recent standards it was a relatively calm week on the policy front as President Trump dialed down his tariff threats, hinting at a de-escalation of tensions with China, and walked back his attacks on Fed chair Powell. Nothing concrete was put on the books, but the tamer messages emanating from the White House was instrumental in arresting a free-fall in the financial markets this week. Stock prices staged a solid recovery, bond yields retreated, slipping well below the nearby 4.5 percent peak reached two weeks ago, and even the beleaguered U.S. dollar reversed its extended decline, bouncing off its thee-year low.

How long the respite lasts is up in the air, as policy uncertainty remains elevated and traders skittish. The economic calendar was light this week, providing little guidance as to what the Fed might do next. For sure, the holding pattern on rates will remain in effect at the upcoming May 6-7 policy meeting. But June has come under more scrutiny as the hard data should start to reflect the impact of tariffs by the time the FOMC meets on June 17. Whether the impact falls more squarely on growth or inflation is the question, but Fed officials will have two more jobs and inflation reports to digest.

Despite this week’s hiatus of anxiety-producing policy news, households remain as nervous and jumpy as ever. The April University of Michigan survey of household sentiment, released on Friday, put the finishing touches on the preliminary survey taken in the middle of the month. Unsurprisingly, people’s nerves remained unsettled, albeit a bit less so over the second half of the month following the announced 90-day pause of the more extreme tariffs and the positive response of the markets. Still, the full-month reading was anything but comforting; if the hard data resembles household sentiment revealed for April, the economy is in for some rough sledding.

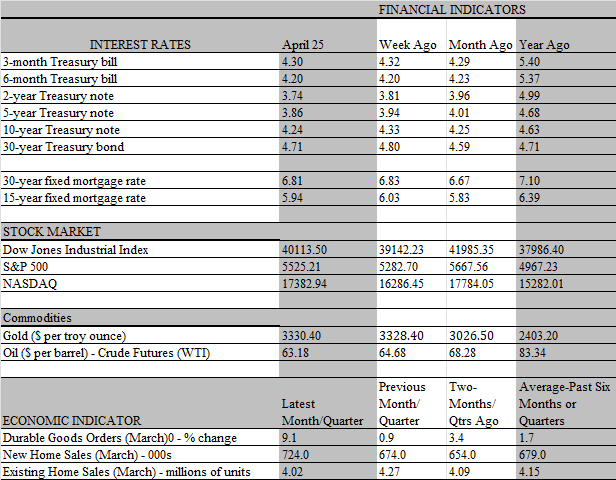

The overall sentiment index fell for the fourth consecutive month, but the real story is what households expect over the foreseeable future. The survey’s expectations for the economy suffered the steepest three-month decline since the 1990s recession. Inflationary expectations were even worse. Households expect inflation over the next year to soar to 6.5 percent, the highest since 1981, and to 4.4 percent over the next 5-10 years, the highest since 1991. Keep in mind that the Fed’s main concern is that inflation expectations are becoming unanchored, something that could become a self-fulfilling prophecy. The silver lining is that market pricing of inflation expectations has remained relatively subdued, with the 10-year breakeven inflation rate at 2.30 percent and the five-year, five-year forward breakeven inflation rate at 2.25 percent. Both are below the levels seen at the start of the month, but both have risen noticeably over the past week.

To be sure, the link between household expectations and their actual behavior is loose and has become weaker in recent years. That’s an important point to remember, as household expectations are being heavily influenced by tariff announcements, which have proven to be chaotic and subject to change at any moment. Should a truce on the tariff front surface and appear sustainable, odds are household sentiment would turn more upbeat. So too would the financial markets, and any sustained wealth-building rally in the stock market would bolster the outlook for spending. Likewise, any retreat in policy uncertainty would brighten the spirits of businesses, where tariffs already on the books have put a crimp on investment spending plans and are wreaking havoc on inventory management.

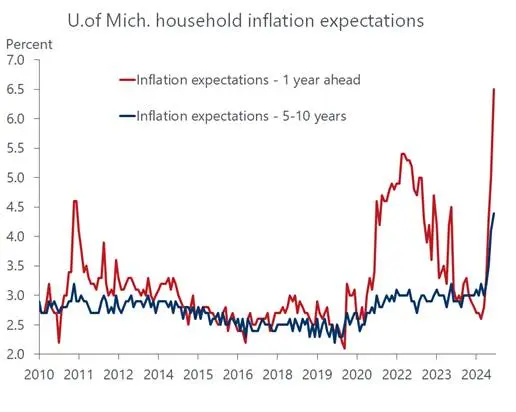

Many business leaders have been vocal about their distaste for tariffs, as they portend higher input costs, stifle global trade and growth, and invite retaliation by trading partners that weakens exports and, hence, revenues from overseas sales. So far, the business angst has not resulted in widespread layoffs, in part because trade tensions might de-escalate and render those dire prospects moot. Companies do not want to be put in the position of firing workers and then struggle to rehire them if pessimistic forecasts are not realized. However, given the risk of earmarking new funds on expensive capital equipment outlays, they are understandably turning more cautious until there is more clarity on the policy front.

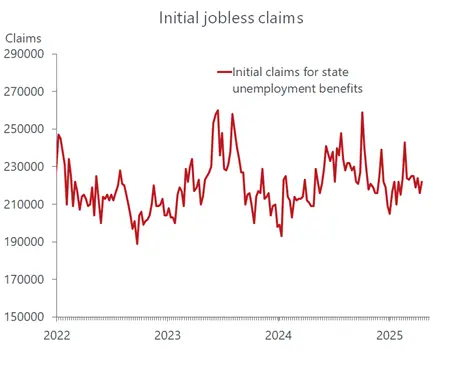

Hence, new orders for nondefense capital goods slipped in February and March following three months of solid gains. What’s more, the reading would have been considerably softer if not for the boost from transportation orders, which were propelled by the front-loading of bookings for autos and parts to beat tariffs scheduled to take effect in April. We expect that capital spending will show a decent gain in the first quarter but turn softer later on unless trade tensions abate significantly and sentiment turns brighter. On a positive note, corporate earnings are holding up, and credit spreads have not blown out, so capital spending should not be weighed down by financial considerations.

Next week will provide important hard data on the economy’s performance, including personal income and spending for March and, critically, the employment report for April. We suspect that once again, the hard data will reveal a brighter picture of the economy than the soft data. As noted, the Fed is not likely to make any rate changes in response to the latest data at its policy meeting the following week. But the meeting will include updated quarterly projections on the economy, inflation, and the federal funds rate. A lot has happened since the previous quarterly projections were made in December, and all eyes will focus on whether the tumultuous events of the past three months have influenced the Fed’s thinking.