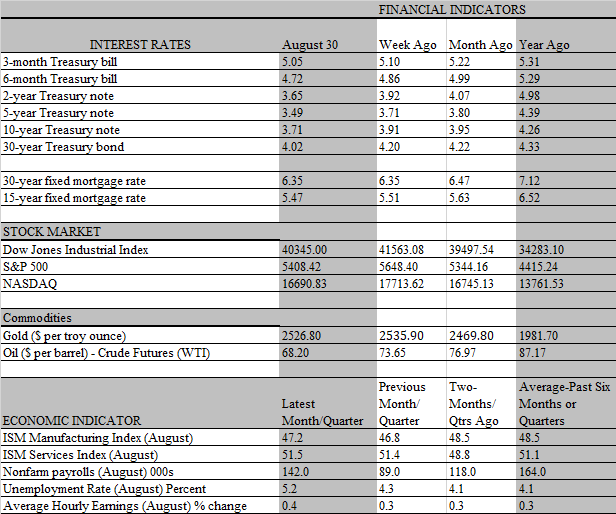

Amid this summers sweltering heat, a cooling trend is wafting through the labor market. The chilling effect is just what the Fed ordered as long as it doesn’t result in a freeze. As Fed Chair Powell noted in a recent speech, we don’t seek or welcome a further cooling in labor market conditions. The August jobs report meets that criterion, although it does not settle the question of whether policy makers will cut rates by a normal quarter of a point of a more aggressive half point at the upcoming FOMC meeting on September 17-18.

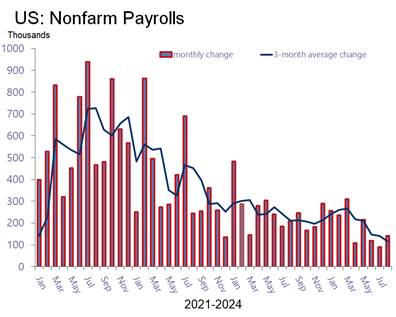

Overall, the report was a mixed bag, but there is nothing alarming in it that should push the Fed towards the larger cut. The economy did generate fewer jobs than expected during the month, with the 142 thousand increase in nonfarm payrolls falling short of the consensus estimate of 165 thousand. But the increase was an improvement over the sluggish 87 thousand increase in July, which was revised down from 114 thousand, and the 118 thousand increase in June, revised down from 189 thousand. The downward revisions are typical in a slowing economy, just as upward revisions tend to occur when the economy is heating up. This pattern would suggest another downward revision next month; its worth noting, however, that the initial August estimate by the Labor Department has been revised up in ten of the last thirteen years.

Even with the modest improvement in August, job growth averaged 116 thousand over the past three months, the slowest pace since the depths of the Covid-19 recession in mid-2020, when companies purged a massive 22 million workers from payrolls over a two-month period. But the modest rebound in August confirms that the job market is not falling off a cliff. Importantly, the unemployment rate ticked down to 4.2 percent following a rise to a near four-year high of 4.3 percent in July that stoked recession fears. That worrisome spike reflected a wave of layoffs of temporary workers, many of which were rehired in August. Had companies continued to slash their temporary staff, there would be more cause for worry, as that typically portends an increase in permanent layoffs.

But as Richmond Fed President Barkin recently commented, we are in a low hiring, low firing mode and there was little in the August jobs report to dispel that notion. Companies are still holding on to workers, as evidenced by the historically low level of claims for unemployment insurance. Just as the temporary slump in job gains was arrested in August, so too was the brief spike in initial claims for jobless benefits in July reversed last month. The July increase in claims (as well as the sluggish payroll increase) received some confirmation from the JOLTS report released earlier in the week, which showed that layoffs and discharges rose during the month even as job openings fell. The latest employment report as well as the trend in unemployment claims suggest that conditions firmed up a bit in August.

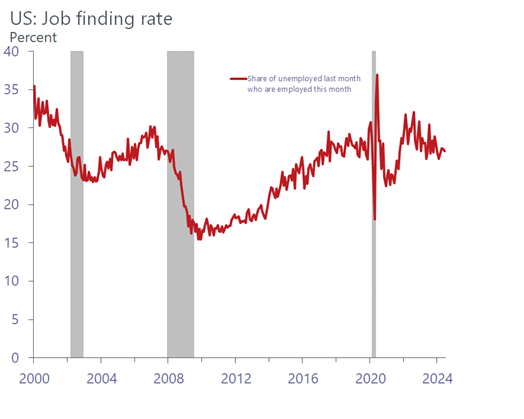

Simply put, the August employment report confirms that the labor market has downshifted into a slower lane but is far from the stall speed that would indicate a recession is just around the corner. Indeed, there were several bright spots in the report in addition to the drop in the unemployment rate. The 80.9 percent share of the prime age population (age 25-54) holding jobs equaled the highest since 2001. Meanwhile, unemployed workers are still able to find a new position reasonably quickly, which is one reason new filings for unemployment claims have not picked up significantly. In August, the job finding rate ticked up although it is trending erratically lower. If unemployed workers were confident about getting rehired quickly, they are not likely to apply for unemployment benefits. The opposite, of course, is also the case. In recent months there has been a modest, but not significant, increase in the share of workers who are unemployed for more than 15 weeks. At 21.3 percent, it is not much above the year-earlier share of 20.6 percent and mirrors the erratic climb in first-time claims for jobless benefits.

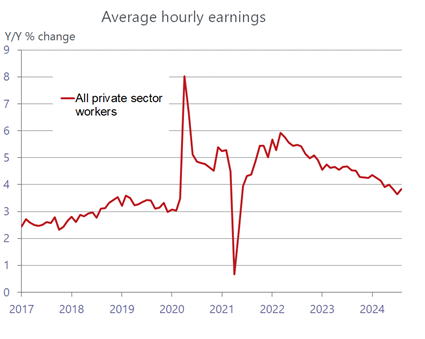

What’s more, worker pay continues to increase at a solid pace, as average hourly earnings advanced 0.4 percent in August following a 0.3 percent increase in July. That lifted the year-over- year increase to 3.8 percent from 3.6 percent. On the surface, that would seem to be bad news for the inflation-fighting Fed striving to curb rising labor costs. But the annual increase in wages has been trending decisively lower for the past two years and is only a tad above the pace consistent with the Feds 2 percent inflation target, after adjusting for the trend-like 1.5 percent increase in productivity. Importantly, productivity has recently surged, rising by 2.7 percent over the past year. By this metric, worker pay is already rising below the pace consistent with a 2 percent inflation rate (2.7 percent productivity plus 2.0 percent inflation could support 4.7 percent wage growth).

To be sure, the monthly data on average hourly earnings are noisy and heavily influenced by changes in the composition of job gains. Odds are the declining trend in wage growth will resume as labor conditions continue to soften. From our lens, the labor market will not be a source of inflation going forward, although some potential catalysts from a looming dockworkers strike or supply disruptions from geopolitical tensions could become greater factors. However, the Fed no longer needs to lean on the economy or the job market to pursue its 2 percent inflation target. Instead, its focus will shift towards staving off a further weakening in labor conditions, which would heighten the risk of a recession.

The financial markets consider it a coin flip as to whether the Fed will cut rates by 25 or 50 basis points at its upcoming meeting. The downshifting of job growth over the past three months has clearly raised the odds of a half-point reduction but we still believe the urgency for the more aggressive move is not warranted. For one, it might signal to the markets that the Fed sees more weakness in the economy than the data currently reveal and stoke unnecessary recession fears. For another, most incoming data on the real activity continue to be solid. Consumers are still spending, buoyed by sturdy income growth, healthy balance sheets and, more recently, improving sentiment. If conditions weaken more dramatically than expected, the Fed could always step on the monetary accelerator in its meetings in November and December. Indeed, there is a higher probability that the Fed will cut rates in both months, instead of just December, than we thought a few weeks ago. With the labor market in far better balance and the disinflation trend firmly entrenched, the stage is set for the Fed to abandon its highly restrictive stance and normalize policy is quickly as possible.