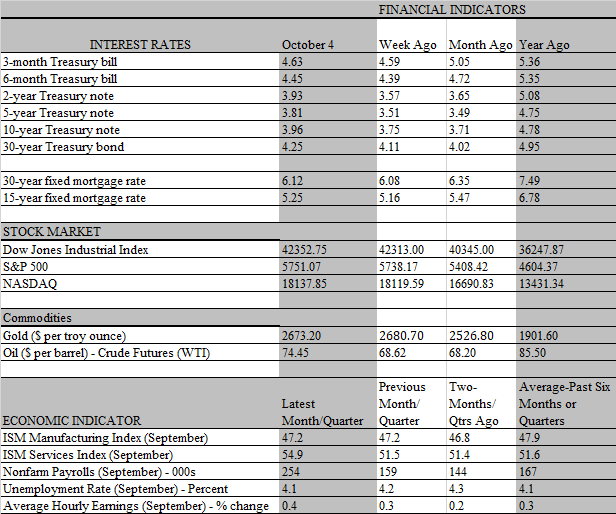

One big external shock was taken off the table late Thursday, when the longshoremen agreed to suspend their strike until January, allowing negotiations to continue. With the ports reopening, the prospect of pandemic-era supply disruptions, steep price hikes on many goods and widespread furloughs have been derailed, at least for several months. Even so, the economy, not to mention the financial markets, is not exactly residing in calm waters. Two other shocks are still injecting considerable uncertainty into the near-term outlook. Mother Nature is always a potentially disruptive influence, and Hurricane Helene dealt one of the more devastating weather-related blows to the economy since Hurricane Katrina. The economic fallout from the destruction of property and cleanup is still being tabulated but could exceed $150 billion.

As is the case with most past hurricanes Helene will cause distortions in some upcoming data but its net impact on macro conditions for the fourth quarter is likely to be mild. What’s destroyed will be rebuilt and the immediate drag on activity will be recouped when weather conditions normalize. That said, the Atlantic hurricane season lasts until the end of November, so there is still the potential for further mischief in the months ahead. Indeed, the National Hurricane Center is reporting that two more storms are gaining strength in the Atlantic and heading towards the U.S. East Coast.

But while the impact of weather-related shocks is transitory, the intensifying geopolitical tensions in the Middle East can have longer lasting and more pervasive consequences for the U.S. as well as the global economy. The price of crude oil has already shot up by more than 10 percent this week and some industry analysts believe that under the worst-case scenario (attacks on Iran’s energy infrastructure or Iran’s closing of the Hormuz Strait) could drive the price up to over $100 a barrel from the current $74-$75 although the price shock could be diluted if Saudi Arabia releases some of its abundant spare capacity. That, in turn, would boost gasoline prices, which acts as both an inflation driver as well as a tax on consumers.

Not surprisingly, the ramped-up hostilities in the Middle East are heightening uncertainty and volatility in the financial markets. But the Federal Reserve is less concerned with exogenous developments and instead laser focused on organic conditions in the U.S. At its last FOMC meeting, which featured an aggressive half- point cut in the federal funds rate, Fed Chair Powell noted that any further weakness in the labor market would not be welcomed. Expectations of another unconventional half point cut at the November 5-6 policy meeting immediately shot up and priced into the financial markets. Once again, however, it appears that the markets raced ahead of actual developments.

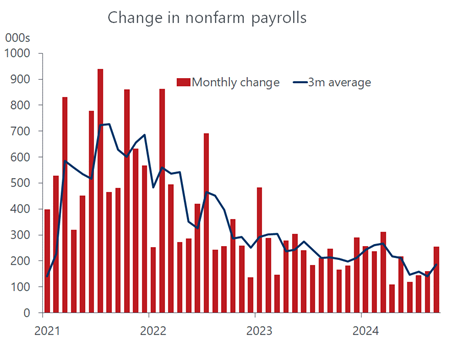

The September jobs report released on Friday strongly suggests that Powell has less reason to fret over labor market conditions than indicated by his earlier comments. At the same time, the prospect of another aggressive half-point rate cut at the November meeting now seems highly unlikely. Simply put, the latest employment report undercuts fears that the job market is poised to fall off a cliff. On the surface it points to just the opposite, that the demand for workers is picking up. Overall, job growth blew past expectations last month, with nonfarm payrolls staging the strongest increase in six months; the 254 thousand gain dwarfed consensus expectations of a 150 thousand increase. What’s more, the estimates for the previous two months were revised up by a combined 72 thousand, which makes the recent trend look much sturdier than before. Prior to revisions, the three-month average increase slipped to a tepid 116 thousand through August from 225 thousand over the previous five months. Following the revisions and including the September gain, the three-month average increase in jobs shoots up to 186 thousand.

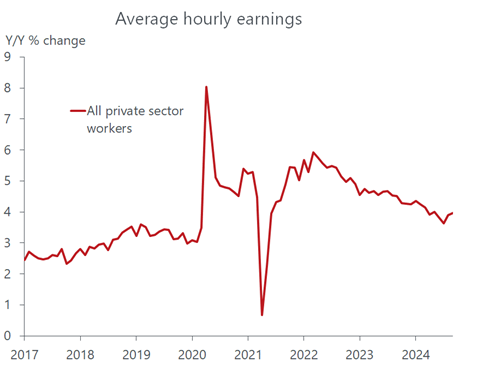

Other aspects of the jobs report also portrays more strength than weakness. The unemployment rate slipped from 4.2 percent to 4.1 percent. That’s still up from a 55-year low of 3.4 percent hit In April of last year, but low by historical standards. Meanwhile, average hourly earnings increased by a solid 0.4 percent, lifting the annual increase to 4.0 percent from 3.9 percent in August. Nor was the strength in the jobs report narrowly based, as 57.6 percent of private industries expanded payrolls in September, the broadest since January and up from less than 50 percent in July when recession fears were understandably running higher. The upside surprise in the headline readings in the jobs report had an immediate impact on the financial markets. Stocks rallied and yields jumped, with the policy-sensitive 2-year Treasury yield leaping by more than 20 basis points, reflecting newfound expectations that the Fed will scale back rate cuts in coming months. The prospect of another half-point cut in both November and December has been fully priced out of the market on Friday.

While the headline metrics in the jobs report may vanquish fears that the economy is in for a hard landing, it would be a mistake to think that it is off to the races. Nor should it imply that labor costs will be a greater source of inflation pressure. The increase in average hourly earnings is not what the Fed would like to see, but it is unlikely to derail its rate-cutting campaign. For one, monthly changes can be noisy, depending on the composition of job changes from month to month. For another, wage increases of roundly 4 percent is not inconsistent with the Feds 2 percent target given the recent strength in productivity. Nonfarm productivity increased 2.7 percent over the past year which would accommodate a 4.7 percent increase in labor costs at a 2 percent inflation rate. However, neither the recent productivity nor the wage gains implied by the average hourly earnings is likely to be sustained.

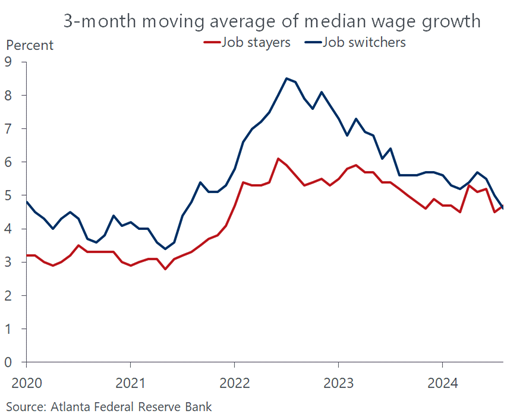

Looking under the hood of the jobs report uncovers some weaknesses that are more consistent with anecdotal evidence on labor market conditions. Individuals are reporting that jobs are harder to get in the latest Conference Board survey. While household surveys do not always align with hard data, that grimmer mindset is supported by some key underlying details in the jobs report as well as the more comprehensive measures of churn in the Labor Departments JOLTS report. The latter, for example, reveals that fewer workers are quitting their jobs, a sign that confidence in landing a new position has slipped, and the wage incentive to do so has narrowed. According to the Atlanta Federal Reserve wage tracker, job switchers received a lower wage increase than job stayers in August for the first time since 2010.

The rise in worker insecurity is also validated in the monthly jobs report, which shows that it is taking longer for unemployed workers to get rehired. The percent of unemployed workers out of a job for more than 6 months has increased to the highest level since January 2022. A similar climb occurred for workers unemployed for 15 weeks or longer. This may be keeping more workers on the sidelines, as reentrants to the labor force fell for the second consecutive month in September. Meanwhile, even the upside surprise in average hourly earnings comes with a caveat, as the increase was offset by a drop in the workweek. Hence, weekly earnings were virtually unchanged during the month.

On balance, it would be hard to deny that the September jobs report featured more strength than weaknesses, particularly coming on the heels of sizeable upward revisions to payrolls in the previous two months. But the headline strength masks some underlying fragility that should become more visible in coming months. Importantly, it should not alter the path of disinflation underway nor deter the Fed from cutting rates. Even with the upside surprise in payrolls last month, the labor market is softening; job growth over the last six months has averaged 167 thousand compared to 251 thousand in 2023. That said, the muscular payroll increase in September does reduce the need for another aggressive rate cut at its November policy meeting. We look for cuts of 25 basis points in both November ad December.