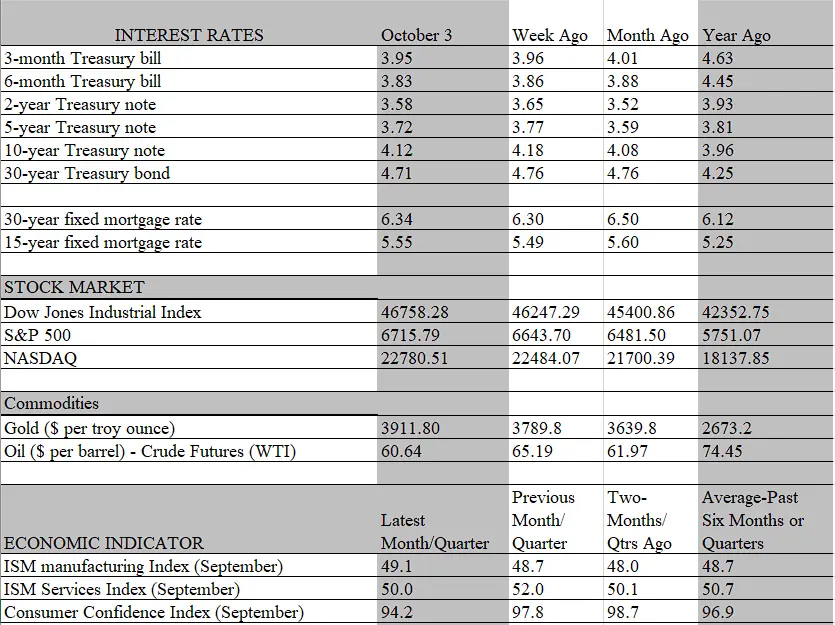

We thoroughly expected to delve into the all-important September jobs report this morning but, of course, the BLS, the agency responsible for releasing the report, is shut down along with most of the rest of the government. How long this lasts remains to be seen. But a few things regarding the link between shutdowns, the financial markets, the economy and monetary policy are worth noting. It’s also important to note that economists – and policy makers—are not exactly “flying blind” as some headlines purport. The private sector provides some valuable information to process and the financial markets, of course, are influenced by myriad forces beyond government data. Indeed, government shutdowns rarely happen without advance notice, and this one has been telegraphed for some time. Unsurprisingly, investors had priced in the impact long before the doors closed, and the aftermath so far has seen little ripple effects. Stocks continued to race to new highs and interest rates have barely budged.

But in the absence of government reports there is always the risk that policy makers will over rely on private data and anecdotal information to guide decisions. We suspect that the Federal Reserve, which has publicly stated it is taking a risk management approach to policy decisions, is more fearful of what it can’t see than what’s visible. The quarter- point rate cut taken at the September FOMC meeting was not based on compelling evidence that the economy needed a boost. Indeed, top-line data on growth suggested the economy retained far more strength than thought. GDP growth for the second quarter was revised higher, from 3.3 percent to 3.8 percent, and available data for the first two months of the third quarter is tracking a similar robust pace; the Atlanta Federal Reserve’s GDPNow gauge is tracking another 3.8 percent increase for the period as of October 1.

But cracks in the job market were becoming more evident prior to the meeting and the Fed opted to take an insurance rate cut to get ahead of a possible collapse in labor conditions. Recall that job growth had virtually stalled out over the three months through August, and the final BLS report before the shutdown (the Jobs Openings and Turnover report or JOLTS) showed that the hiring rate, at 3.2 percent in August, matched the lowest since May 2013 outside of the pandemic. While inflation is still running above the 2 percent target, the Fed believes that it is being temporarily held up by tariffs not by underlying cyclical forces. A deteriorating job market, however, is more worrisome because once it gains traction it is difficult to reverse. Hence, the rate cut was viewed as more of a preventive measure than a need to stimulate growth.

The collection of data needed for the jobs report has already been completed, so the report will be released as soon as the shutdown ends. If the legislative impasse lasts through the middle of October, however, when the data collection for the September jobs report is undertaken, the Fed will again be shrouded in uncertainty regarding labor conditions when its policy-setting committee meets at the end of the month. From our lens, that would just about guarantee a rate cut, as the Fed would have no idea if the floor under jobs had collapsed. Of course, it would also be missing fresh inflation data, but the odds of an inflation flareup amid a collapsing job market is very low.

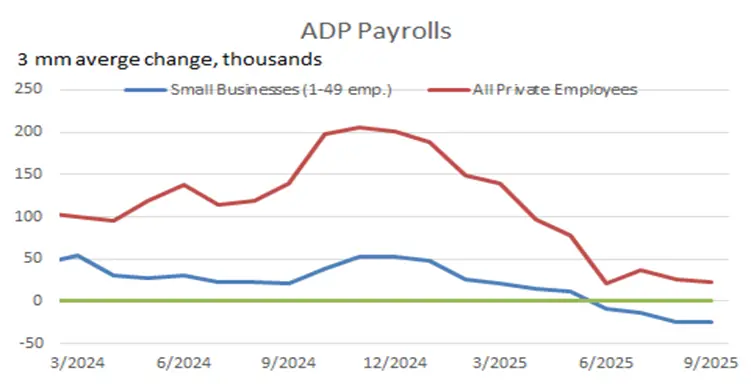

As it is, the data available through private sources is anything but encouraging on the jobs front. On Wednesday, ADP, the payroll processing firm, released its monthly data that revealed a 32 thousand decline in private payrolls in September. This report tends to be very noisy, and the monthly data does not correlate very tightly with the Government’s jobs report. But it does provide an important signal, particularly when the monthly data is smoothed out over a longer period. A look at the three-month moving average tells much the same story as the government report: job growth remains very weak among private companies, with the 23 thousand average increase remarkably close to the 27 thousand average in the BLS data through August.

Additionally, the ADP report provides important detail into hiring behavior by firm size. What the September reading confirms is that smaller firms are having a hard time. Employment by firms with less than 50 workers declined by 40,000 in September, while firms with more than 500 employees added 33,000 jobs. Small businesses are under pressure from a weakening in sales, elevated input costs thanks to tariffs, and high interest rates. Tariffs are widening the gap between small and large businesses, as larger firms have the financial wherewithal to front-load imports and have more pricing power. Conversely, small businesses have less muscle to renegotiate contracts with foreign manufacturers and it’s more difficult to pass tariffs onto the consumer.

Keep in mind that the ADP report, as well as others such as from Challenger and Gray, only tells one side of the story – the hiring side. It says nothing about the supply side – i.e. what is happening to the labor force due to immigration, retirements, drop-outs, new entrants, etc. Hence, it provides no information about the unemployment rate, or how much slack is building up in the labor market. That said, the JOLTS report, as well as layoff announcements, confirm that businesses are still hoarding labor, eschewing widespread firings that would clearly drive the jobless rate up and heighten the risk that a recession is looming. All that can be said at this juncture is that the “low hiring/low firing” narrative remains firmly in place.

As long as this condition continues, some believe it conveys more positive than negative news for the markets, particularly if it coexists with strong top-line growth in GDP. For one, it implies that growth is being powered by productivity gains, something that augurs well for profits and wages. Others are not so sanguine, believing that productivity-driven growth leads to more income and wealth inequality that poses a host of risks to the economy via political and social turbulence as well as heightened uncertainty. But the more immediate unknown that is vexing policy makers is the uncertain health of the job market. Most forecasts for September are that more jobs were created than lost in September and that the outright decline that occurred in June – the only one since the pandemic – was an outlier.

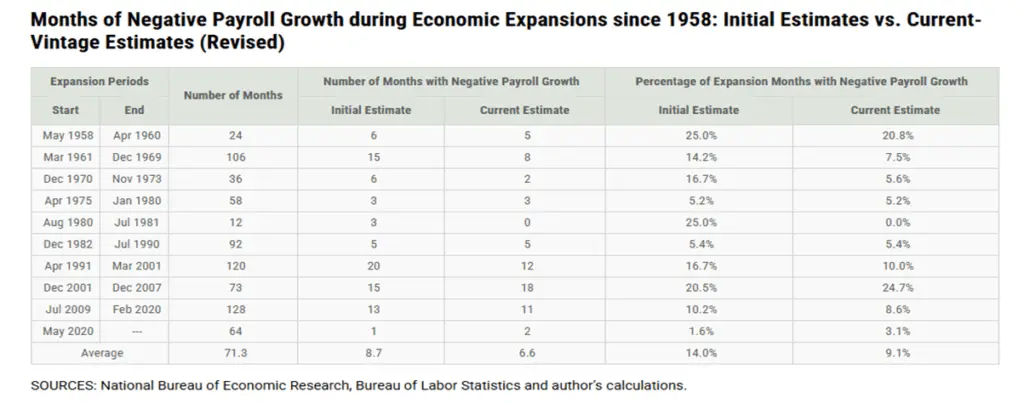

On this score, it’s important to remember that even if September turns out to be weaker than forecast and shows another drop in payrolls when the report is ultimately released, it would not be unusual during an expansion. Nor would it mean that a recession is just around the corner. We came across an interesting research note by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis that shows how common monthly declines in employment are during expansions. In fact, the one decline during the current expansion stands out as the outlier among the ten previous upturns. On average, the economy suffered about 9 monthly job losses during expansions, according to the initial employment reports, and about 7 after the initial estimates were revised. It’s possible that future revisions will deliver more job losses than the 1 seen so far this time, but as of now, the labor market is exhibiting more resilience than in past expansions.