The window of economic news opened a crack on Friday, as the government recalled statisticians from the Labor Department to produce the September consumer price report, a necessary action to calculate the COLA adjustment for next year’s social security benefits. This might be a case of “enjoy it while you can”, because the government shutdown shows no sign of ending and data collection for the October report is already in jeopardy. That said, the report released on Friday morning was viewed as a welcome relief by the markets, as it portrayed a benign inflation picture during the shutdown so far, which opens the door wider for a Federal Reserve rate cut next week. To be sure, that prospect was already baked into expectations and well telegraphed by Fed officials. It’s unlikely that the CPI report would have swayed the Fed’s decision under a different outcome.

Still, the key headline inflation indicators came in more subdued than expected, which should keep inflation expectations anchored and validate the Fed’s pending rate cut. It’s important to remember, however, that the Fed is not stepping on the accelerator to jump start the economy’s growth engine. Instead, it would be easing up on the brake, moving the short-term policy rate slightly closer to neutral, where it would neither stoke nor impede activity. That landing spot would put the federal funds rate at about 3 percent, slightly more than 1 percent lower than the current level. How fast it gets there remains to be seen. At its last policy meeting, officials expected to make two quarter point cuts this year, leaving it in a range of 3.50-3.75 percent heading into 2026.

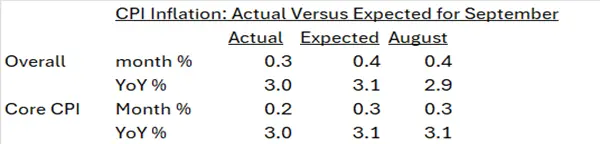

The path to the neutral level depends on how prices behave and how well the economy performs. With the shutdown still underway, there is little fresh information on the economy’s current performance. The CPI report at least raises the curtain somewhat on the inflation front. The good news is that the overall level of consumer prices rose by less than expected, something shown in the following table that includes expected outcomes based on Bloomberg surveys. As can be seen, both the monthly and yearly results fell a tad short of expectations with both the headline and core CPI, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, increasing by 3.0 percent over the past year.

The bad news is that 3.0 percent is still a hefty margin above the Fed’s 2 percent target, confirming the sticky nature of the inflation trend that prevents the Fed from moving more aggressively to counter a weakening labor market. It also means that social security recipients will be getting a cost-of-living bump of 2.8 percent starting in January, based on a separate measure for the July-September period. While that’s a welcome development for seniors, it doesn’t quite keep up with the higher costs that this cohort incurs, as it fails to fully capture the above trend rise in prices on the goods and services that these citizens tend to buy, most notably for medical care. The Labor Department compiles a separate experimental measure designed to better represent the cost-of-living for people over 62, but it was not released at the time of this writing. When it is, we will have more to say on this issue.

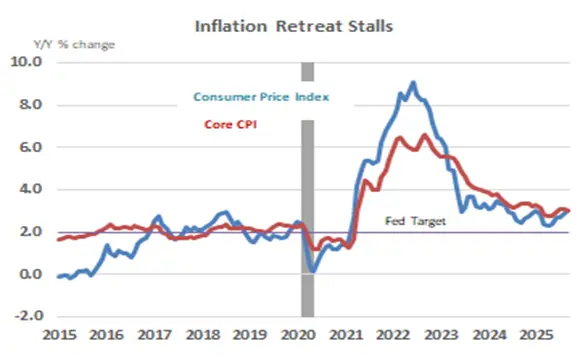

As the following chart shows, inflation has fallen sharply since the pandemic peak in the summer of 2022. But it has been moving in the wrong direction since this spring. The key reason for the mild uptrend is not difficult to find, tariffs. Admittedly, the levies imposed since the liberation day tariff blitz have not generated as much of an inflation boost as expected. By our calculations, about two-thirds of the tariffs have been passed on to consumers, contributing about 0.4 percent to inflation. Hence, absent the tariffs, inflation would be running about 2.5 percent, not 3 percent. We caution, however, that the pass through is poised to increase, as the ability of importers – the chain of suppliers from manufacturers to wholesalers to retailers – to absorb the higher costs of imported goods is weakening due to the squeeze on profit margins.

Another boost to inflation last month came from higher gasoline prices, which is likely to continue in coming weeks thanks to the latest sanctions on Russian oil announced this week. Actually, the increase in September was more of a statistical artifact than an outright increase. Simply put, gasoline prices fell by less than is usual at the end of driving season, so after applying the usual seasonal adjustment prices rose by an outsized 4.1 percent for the month. If the jump in crude prices in recent days following the announced sanctions stick, look for an even steeper gasoline price increase for October, whenever that report is released.

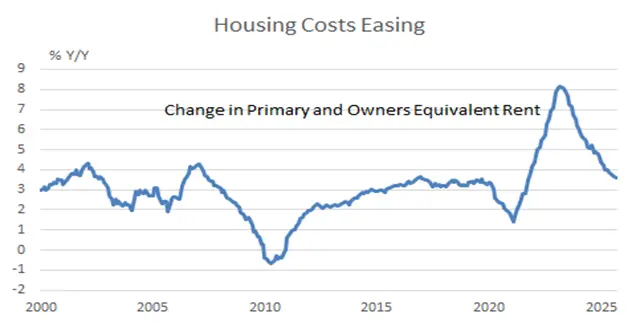

But the leap in gasoline prices did not have a major impact on the overall index because it was offset by declines elsewhere. Most notably, housing costs – which has a 40 percent weight in the core CPI – subsided last month. The overall increase in shelter costs slowed to 0.2 percent, lowering the increase over the past year to 3.6 percent. That’s the slimmest annual increase since October 2021, and industry indicators of market rents point to continued declines in coming months. Services prices outside of housing rose a touch more than in August, with notable gains in hotel prices (+1.7% m/m) and airfares (+2.7% m/m). The latter will have gotten a lift from jet fuel prices, but the turnaround in prices of travel-related categories speaks to the sharp rebound in discretionary spending in the second half of the year, driven by high-income households.

Still, the easing of housing costs is a welcome development for budget-strained middle-to-lower income households, who spend a higher fraction of income on housing than their wealthier counterparts. The easing of rents will go a long ways towards increasing housing affordability, as homeowners and builders compete with apartments for people looking for shelter. Lower rents put pressure on home sellers to lower prices to make a sale. But home sales are also getting help from another source – lower mortgage rates. Thanks to benign inflation readings, Fed rate cuts and signs of a weakening labor market, market yields have fallen considerably in recent months, with the 10-year Treasury yield falling through 4 percent this week for only the second time in two years.

Mortgage rates are heavily influenced by this yield and, not surprisingly, have also been falling. In the latest week, the 30-year mortgage rate slipped to 6.19 percent, the lowest since September 2024. Importantly, the decline may be starting to lure home buyers off the sidelines, as sales of previously owed homes increased in September. However, a bigger impact on the broader economy would occur through refinancings, particularly if mortgage rates fall through 6 percent. That would free up a huge amount of housing equity built up in recent years, which would enter the spending stream and partly offset the drag from tariffs.