Following the blockbuster jobs report last week, there was extra scrutiny placed on this weeks inflation reports. The overriding question is whether the data would validate or undercut the Feds rebalancing of risks, from worrying about elevated inflation to concern over a deteriorating job market. The jumbo half-point rate cut taken at the mid-September policy meeting clearly reflected growing angst over weakening labor conditions that officials hoped to curb before it was too late. But the surprisingly muscular job growth in September, reported two weeks after the meeting, made that decision seem questionable. As it turned out, the minutes from that meeting, also released this week, revealed that there was broader sentiment among committee members for a conventional quarter point cut than thought, suggesting that some arm-twisting may have occurred at the confab.

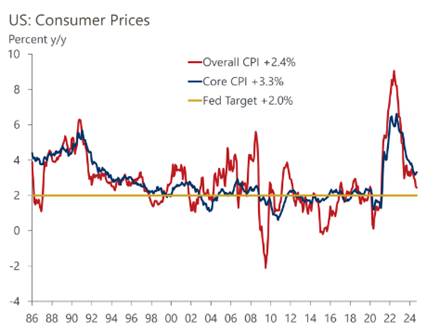

At first glance, the consumer price report released this week bolsters the case of officials who preferred the more gradual approach. Overall inflation did tick down again in September, but not as much as expected. The 2.4 percent year-over-year increase in the CPI slipped 0.1 percent from the annual increase in August and was the lowest since February 2021. The consensus, however, expected a bigger drop and if not for a sizable fall in gasoline prices, the direction of change would have been higher. Excluding the 1.9 percent drop in energy prices during the month, weighed down by a 4.1 percent decline in prices at the pump, the CPI increased 3.3 percent from a year earlier, up from 3.0 percent in August. A big influence on the nonenergy rise was food prices, which rose by 4.1 percent, matching the strongest gain since January 2023.

To be sure, food and energy prices are noisy from month to month, but the core inflation rate, which strips out those items, was also somewhat disappointing. The core CPI rose 0.3 percent in September, the same as in August, and the increase from a year earlier ticked up to 3.3 percent from 3.2 percent. Simply put, the road to the Feds promised land of a 2 percent inflation rate is turning out to be as advertised bumpy with twists and turns in its path. The latest detour, however, is not alarming and should not impede the disinflation process. The journey may take a bit longer than the Fed would like, but officials are prepared to modify its reaction function. If inflation proves to be stickier than expected, the policy response will adjust accordingly. Unsurprisingly, the latest CPI report solidified the shift in market expectations that followed the muscular jobs report. The odds of another jumbo 50 basis point reduction at the upcoming November policy meeting have been reduced to near zero, and there is a nontrivial expectation that the Fed will skip a rate cut entirely at the meeting.

While the Fed may move to the sideline next month, we still believe the mindset to continue normalizing rates will remain intact. Some officials may have wanted a smaller cut at the September meeting, but none expressed a desire to delay the normalization process. Even after the September move, short-term rates remain restrictive, and it is unclear how much firepower the economy has to withstand a sustained growth-retarding stance. The headline job growth did surprise on the upside last month, but labor conditions are trending softer. External shocks from Hurricanes Helene and Milton as well as escalating uncertainty linked to Middle East hostilities and the looming presidential election pose a downside threat to the job market over the near term. The Fed may want to provide a stabilizing force amid a swirl of disruptive events that could send the economy reeling.

What’s more, the somewhat disappointing headlines in the CPI report masks some encouraging features underneath the hood. Most notably, shelter prices a major source of sticky service inflation downshifted markedly in September, rising only 0.2 percent following a dispiriting 0.5 percent increase in August. This lagging CPI component may finally be capturing the slowdown in market rents that industry sources have been reporting for months. Unfortunately, that bit of good news was offset by another sharp increase in insurance and repair costs on motor vehicles. But these increases are still catching up to the steep rise in auto prices in 2021 and 2022, which have since been arrested. Service prices also came under pressure from a surprising leap in medical care costs; but that followed two consecutive months of negative readings and should not be sustained.

Its also important to remember that the Feds preferred inflation gauge is not the CPI but the personal consumption deflator. That measure, which will be released later this month, should mirror the trend in the CPI report, revealing slow, albeit bumpy, progress towards the 2 percent target. We expect the headline PCE deflator to increase just a hair above 2 percent in September compared to a year ago, and the core PCE to slow a tad from 2.7 percent to 2.6 percent. Because of the high base against which it will be measured, the year-over-year progress in the core PCE will be harder to come by over the remainder of the year, supporting a more cautious easing policy by the Fed. The wildcard in the near-term outlook for policy is how badly the hurricanes and the ongoing Boeing strike will impact the upcoming jobs report, and how patient would the Fed be in the face of a more dismal reading than expected. The October data will come out just days before the next FOMC meeting on November 5-6.

Our sense is that it would look past the jobs report and focus on the larger picture, which still looks promising for a soft landing. Labor costs should not be a source of upward pressure on inflation, as wage gains are being offset by strong productivity growth. Meanwhile, price-conscious consumers, who are becoming much more selective shoppers, are also keeping price increases in check. Importantly, workers are staying ahead of inflation, as wages are outpacing price gains. That was evident again in September, as real average hourly earnings continued to rise, paced by sturdy gains among blue-collar workers. Hence, even with expected slowing in job growth next year, consumer purchasing power should provide solid support for spending.

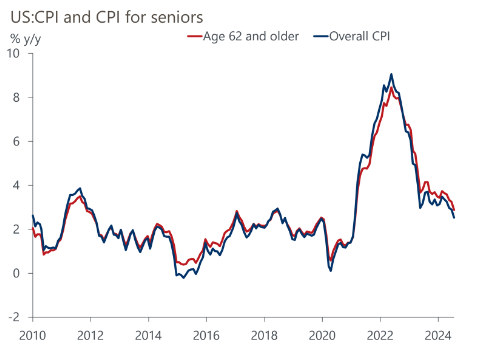

As a footnote to the usual CPI report for October, the government reveals the cost-of-living adjustment that seniors will receive in their Social Security checks next year. For 2025, the increase will come to 2.5 percent, which is less than the 2.9 percent inflation rate for seniors over year through August, as measured by an experimental alternative measure the Government has been calculating since the 1980s. The senior measure comes out with a one-month lag, but its doubtful that the gap was closed in September. Indeed, the spike In medical care costs in September suggests just the opposite is the case.

For most of the past two years, seniors have seen prices for the goods and services they buy rise faster than for the general public. Perhaps not coincidentally, they have either been rejoining or staying longer in the labor force over the period to maintain purchasing power. From early 2021 to late 2022, seniors fully participated in the so-called Great Resignation as the labor force participation rate for people 65 and over fell from 20.8 percent to 18.3 percent. Since then, however, the trend has reversed, with the elderly participation rate shooting up to 20.0 percent in September. That’s a stronger increase than the overall participation rate, which has been pumped up by an influx of younger migrants. Keep in mind that the elevated level of interest rates in recent years benefited older people, as there are more savers than borrowers in this population cohort. It will be interesting to see if the rate cutting campaign of the Fed drives more of them into the labor force.