The headline-grabbing presidential election took center stage this week, and the outcome is still reverberating through the financial markets. Stocks continued to stage an unprecedented post-election rally through Friday although the immediate spike in bond yields was entirely erased towards the end of the week. Commentators and pundits will spend weeks on end debating what the incoming presidents policy proposals will mean for investors. The prospect of higher tariffs, lower taxes and more deregulations appears to be on the way and the consensus view is that the mix points to faster growth and, possibly more inflation than otherwise. The stronger growth prospect and looser regulation added fuel to the stock market rally, while the bond market struggled to understand the inflationary ramifications that might evolve from a Trump administration.

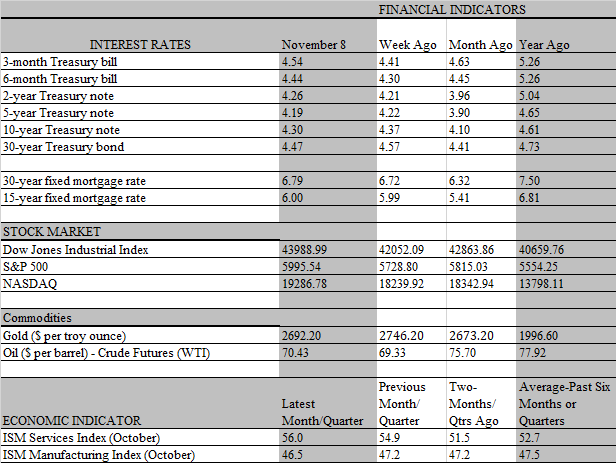

While not nearly as much of a market mover, another critical vote also took place this week, as members of the Federal Reserve rate-setting policy committee elected to cut interest rates by a quarter-percentage point. The move, on the heels of the jumbo half point cut in September, was widely expected and, hence, elicited a muted response in the markets. What is up in the air is what comes next. At its September meeting, the Fed projected another quarter point reduction in rates before the end of the year, a well as a full percentage point of cuts in 2025. However, that projected course of action is now shrouded in uncertainty. In his post-meeting press conference this week, Fed Chair Powell was noncommittal about what would take place at the December meeting, noting that policy is not on a preset course. Unsurprisingly, the markets dialed back expectations regarding another rate cut at that confab, as well as the full point reduction in 2025 that were projected at the September FOMC meeting.

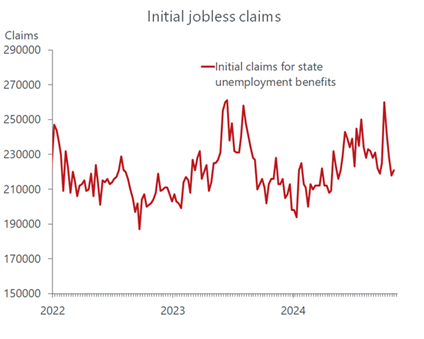

Clearly, the case for another rate cut in December is less compelling than in September, when the economy seemed to be buckling and the job market poised to fall off a cliff. Since then, the economic landscape has turned considerably brighter, notwithstanding the disruptions caused by two hurricanes and a now-settled Boeing strike. Consumers are still spending freely, business investment is strong, particularly for productivity-enhancing equipment and, importantly, the job market remains on a solid footing. Hiring is slowing, but employers continue to hold on to workers, keeping unemployment near historically low levels and a lid on first-time claims for jobless benefits. That said, rates remain in restrictive territory and there is no question that the Fed intends to bring them down to normal levels. The question is, where is the landing spot or the so-called neutral rate the one that neither juices nor curbs activity in a stable inflation environment and how fast should the Fed get there.

Powell confirmed that these questions are still unresolved. As he said previously, the neutral rate is a moving target and not measurable in real time. The only acknowledgment is that it is lower than the current level of rates, confirming that policy is still viewed as being restrictive. Hence, more easing is in the cards as Fed officials strive to normalize policy. That said, the pace of easing may not be as aggressive as expected at the September meeting. Indeed, the policy statement following the meeting tweaked the September statement in a significant way, removing the phrase the Committee has gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainable towards 2 percent.That tweak is likely a subtle acknowledgement of the heightened uncertainty in the inflation outlook because of the election, without explicitly saying it.

At this juncture, we still see the odds of another quarter-point cut at the December meeting as a coin toss. Keep in mind that there will be two more inflation and another jobs report leading up to that meeting, which should have a decisive influence on what the Fed does. No doubt, job growth will bounce back from the dismal October reading, which was hugely depressed by hurricanes and strikes. The Fed will need to decide how much of the rebound merely recaptures the shock-related losses in October versus genuine ongoing strength in the U.S. economy. If the latter, the case for skipping a rate cut in December would be bolstered, particularly if a strong rebound in job growth is accompanied by sizeable wage increases.

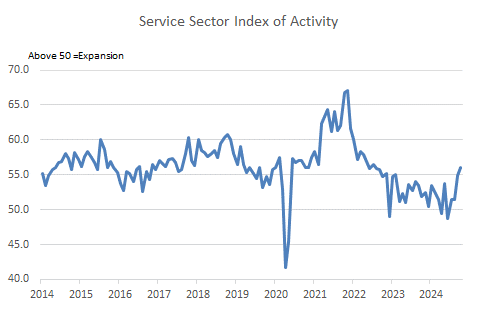

Although this weeks economic calendar was very light, at least one report suggests that the economy still has considerable support from the all-important service sector. The Institute for Supply Management (ISM) reported that its index of service sector activity jumped 1.1 points to 56 in October, which was well above expectations and the highest since July 2022. Notably, the employment component also surprised on the upside, surging 4.9 points to 53, reaffirming that the weakness in the October jobs report was due to special factors rather than weak demand for workers by service providers. If anything, the index may have been held back due to election uncertainty, with one respondent to the ISM survey noting that “business is in a steady state, with everyone holding an even keel awaiting U.S. election results. Its unclear how the election results will impact sentiment in the business community, but there are anecdotal signs that the prospect of higher tariffs is spurring demand for imported goods before the tariffs kick in, which could give a near-term lift to activity.

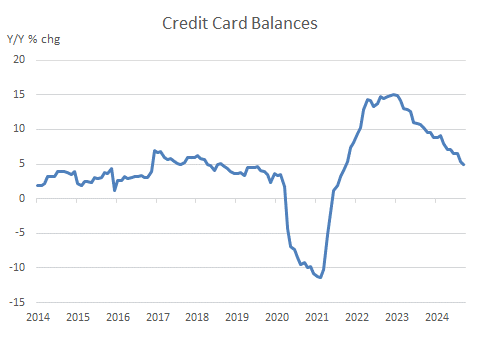

That said, the strength in the service sector comes against ongoing weakness in manufacturing activity, where the ISM Index has remained in contractionary territory for most of the past two years. Unsurprisingly, manufacturers are also downsizing their workforces, cutting 44 thousand jobs over the past four months. Nor are factories the only sector exhibiting weakness. Within the vast household sector, those with lower incomes continue to struggle, having exhausted their pandemic savings and deterred from borrowing by high rates and tightened bank lending standards. Credit card borrowing has stagnated over the past two months, and outstanding balances are growing at the slowest pace since September 2021. The rate cuts by the Federal Reserve may spur some borrowing but that impetus is constrained by the fact that an increasing share of low-income borrowers have reached their credit limits, according to Federal Reserve data.

Simply put, it will not be clear sailing for the economy in coming months. Activity over the near term will receive a substantial boost from reconstruction efforts following the hurricanes and a catch-up in production of airplanes and parts following the settlement of the Boeing strike. The return of more than 40 thousand striking and strike-effected workers will also goose employment in November. But the slowing in job growth prior to these temporary shocks should resume, as the lagged impact of high rates will continue to wend its way through the economy. What’s more, the supply of labor will also come under downward pressure, owing to tightened immigration policies that will almost certainly continue under the incoming administration.

The good news is that the Fed is likely to focus more on shoring up the job market in its rate-setting decisions going forward, as inflation has retreated close to the 2 percent target. The annual increase in Its preferred price gauge, the overall personal consumption deflator, is down to 2.1 percent while the core PCE that strips out volatile food and fuel prices is running a bit higher at 2.7 percent, but cooling. Unless there are stunning upside surprises on the inflation and jobs fronts over the next month, our sense is that the Fed is leaning towards cutting rates by another quarter point at its December meeting. Whether it does or not, perhaps the most interesting reveal at that meeting will be the release of the quarterly set of economic projections That should give us the first post-election clue as to how fast or slow the Fed plans to normalize policy in 2025.