With the courts echoing President Trump’s on-again, off-again tariff decrees, the only sure thing the markets can count on is that the prolonged period of uncertainty is poised to continue. For now, Trump’s latest iteration of tariffs remains in effect thanks to the appeals court ruling on Thursday pausing a lower court order that would have disallowed most tariffs imposed under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act. More legal wrangling is on the radar, which is likely to cause more confusion among households and businesses, not to mention the Federal Reserve, which has put policy on hold until it receives more clarity on the tariff front.

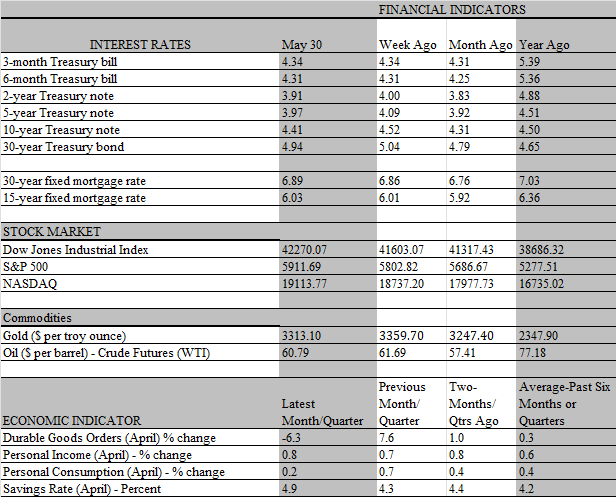

That said, the Fed is data driven and incoming reports provide no reason for it to move off the sidelines. Indeed, the balance of risks between inflation and employment is closer to equilibrium than any time since the pandemic recovery got underway. The job market retains enough strength to keep the unemployment rate near its historical low of roundly 4 percent while inflation is steadily retreating towards the Fed’s 2 percent target. Importantly, the latest personal income and spending report for April reveals that one of the Fed’s preferred inflation gauges, the personal consumption deflator, has virtually closed the gap, rising 2.1 percent over the past twelve months. That’s the closest to the 2 percent target since February 2021.

The Fed’s other preferred measure, the core PCE deflator is still half-percent above target, rising 2.5 percent, but that too has been trending lower and is the closest to 2 percent since March of 2021. Both measures notched a slim 0.1 percent increase over March. To be sure, the tariff impact has yet to seep through to these inflation measures, as most of the goods sold were from inventories imported at pre-tariff prices. As stockpiles are drawn down and replenished with the higher costs linked to tariffs, the pass-through effects will be visible. How much of the higher costs will be eaten by the sellers remains to be seen, but what is not reflected in reduced profits will be seen in higher inflation.

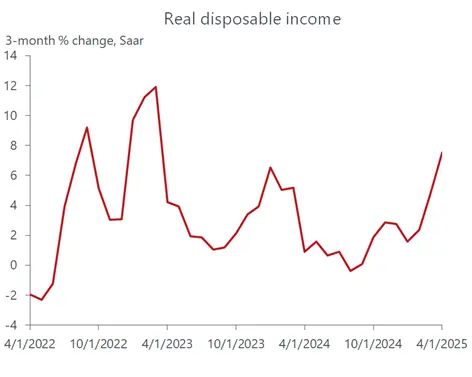

Then the focus will be on how consumers respond. The good news is that household purchasing power is holding up. Wages and salaries increased by a formidable 0.5 percent last month, contributing to a sturdy 0.8 percent increase in personal incomes. That translates into a healthy 0.7 percent increase in real disposable income after subtracting inflation and taxes, Over the past three months, real DPI has increased at an annual rate of 7.5 percent, a pace not seen since early 2023 when copious stimulus payments and tax breaks were bloating household bank accounts. Clearly, this pace will not be sustained. For one, a temporary spike in government social security payments boosted income in April. For another, the job market is softening, pointing to slower wage growth in coming months. Still, we do not expect a meaningful deterioration in labor conditions that would severely undercut wage growth, particularly with labor supply being constrained by tightened immigration policies and large-scale deportations.

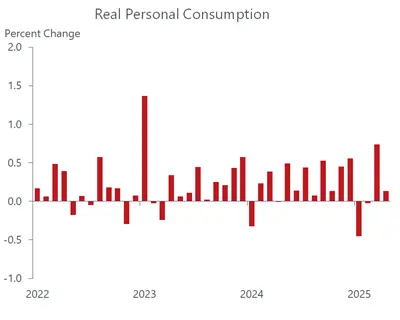

The bad news is that households are not unleashing their purchasing power. Even as incomes staged a healthy increase, spending was sickly in April, edging up by a slim 0.2 percent. In real terms, the gain was a miserly 0.1 percent. True, the April print follows a robust 0.7 percent increase in March, when consumers pulled forward purchases to beat tariff-induced price increases. But that spike does not compensate for the overall sluggish spending trend in the first quarter highlighted by the revised GDP data released this week. Critically, real personal consumption was revised lower from a 1.8 percent growth rate in the preliminary estimate to sluggish 1.2 percent. To put that in perspective, real PCE growth averaged 2.8 percent over the previous three years, and 2.3 percent over the 2010-2019 expansion.

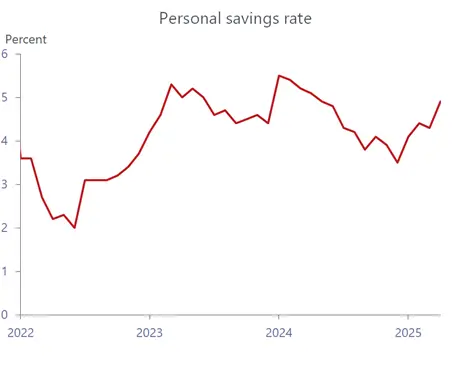

Clearly the recent spending data suggest that households are turning more cautious, which would align with the dismal household sentiment readings. It’s also likely that tariff uncertainty is wreaking havoc with household psychology, causing a gloomy mindset when tariffs are imposed and stoking a rebound in optimism when they are rescinded. So, the question is whether the surge in the savings rate in April, to a one year high of 4.9 percent, reflects a sustained precautionary move by households or a temporary spike fueled partly by social security payments that were not yet spent during the month. We suspect that it reflects a combination of the two but do expect the government transfer payments to enter the spending stream quickly, as lower-income households depend on these payments to maintain living standards.

The Fed will have the latest inflation and spending data when it meets in two weeks, as well as the May employment report. As was the case in recent meetings, it is not expected to make any rate changes, although attention will focus on the updated quarterly Summary of Economic Projections. No doubt, the benign inflation readings combined with consumer caution might nudge some policy makers to the dovish side, portending rate cuts sooner rather than later. But prospective tariff hikes and their inflationary ramifications will have the opposite influence on other officials while the ongoing lack of clarity on tariff policy will keep most of them in a wait-and-see mindset.