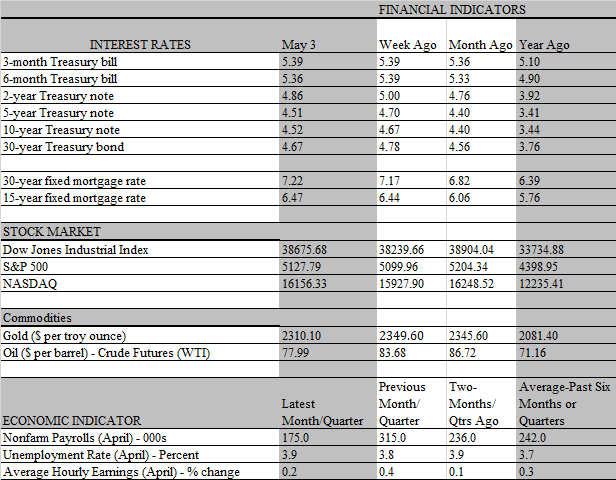

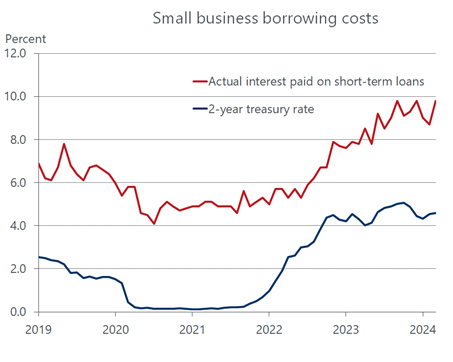

April’s employment report is about as good as it gets. Moderating job growth, looser labor market conditions and slower wage gains, just what the Fed doctor ordered to tame inflation. What’s more, there were few if any devils in the details. The unemployment rate did tick up to 3.9 percent from 3.8 percent in March, but remained under 4 percent for the 27th consecutive month, equaling the longest stretch of time under the 4 handle since the 27-month period ending January 1970. If it stretches for another month under 4 percent, it would be the longest since the Korean conflict in the early 1950s. And, while the payroll gain continued to be dominated by a handful of occupations, most notably health care and social services, which accounted for half of the 175 thousand increase last month, fully 60 percent of industries expanded staff, a healthy swath of the workforce.

Unsurprisingly, the Goldilocks outcome spurred a joyous reaction in the financial markets. Stocks rallied and market yields tumbled immediately following the report’s release on Friday. Actually, investors sounded a positive tone following Fed Chair Powell’s post-FOMC comments on Wednesday, which many thought would be more hawkish than it turned out to be. While he reinforced the narrative that rates would remain higher for longer, there was no indication that a rate hike was in the offing, defusing speculation that such a prospect was being discussed. At his presser, Powell noted: There are paths that the economy can take that would involve cuts, and there are paths that wouldn’t, he said. Note that he did not mention that there was any path that would involve a rate hike.

No doubt, Fed officials welcomed a report that was not too hot, nor too cold. To be sure, a 175 thousand increase in nonfarm payrolls is nothing to scoff at, as it almost spot-on with the average monthly gain in 2019, the last full year of expansion before the pandemic recession struck. But it follows a disconcerting sequence of monthly upside surprises that inflamed concerns the economy was generating too much heat – and outsized wage increases – to wrestle inflation down to the Fed’s 2 percent target. Not only did the report fail to deliver another upside surprise, but it also refreshingly came in under expectations, as the consensus forecast was for a 240 thousand increase in payrolls.

True, it would be a mistake to place too much emphasis on one month, which is subject to revision in the following months. A modest upward revision to the initial March estimate was more than offset by a downward revision to the February data, resulting in a net 22 thousand reduction in payrolls for those two months. That said, the 242 thousand average increase over the past three months represents a model of consistency, matching the 242 thousand average increase over the past six months and 234 thousand over the past 12 months. These trends still exceed the growth in the working age population; but the moderation in April and the downward revision over the previous two months suggest that the labor market is gradually coming into a better balance.

That, in turn, also suggests wage pressures will ease, giving the Fed more confidence that inflation will follow suit and allow it to follow through with its rate-cutting plans later this year. Prior to the jobs report, market expectations for the first rate cut had been pushed back to December, underpinned by a growing sentiment that no rate cuts at all would take place this year. But following the report, that mindset turned more favorable towards an earlier cut, with the futures market pricing in nearly a 50 percent chance that the Fed will pull the trigger in September. While the slowdown in job growth contributed to that shift in thinking, a downside surprise in wages played a key role. Average hourly earnings increased by 0.2 percent in April, a tick lower than the 0.3 percent expected, reducing the year-over-year increase to 3.9 percent from 4.1 percent in March. That’s the smallest annual increase since June 2021. Earnings for blue-collar workers also downshifted, rising by a slim 0.2 percent for the third consecutive months, lowering the annual advance to 4.0 percent from 4.2 percent in March.

The Fed would like to see wage growth slow to 3.5 percent, which would be more consistent with a 2 percent inflation rate after accounting for productivity growth. Average hourly earnings are not the Fed’s preferred wage measure, as it can be noisy and influenced by the mix of job changes. But other indicators point to easing wage pressures, including a decline in the voluntary quits rate to below prepandemic levels. The competition for workers is also slackening, as reflected in the decline in both the level of job openings and its ratio to unemployed workers. Importantly, the more rapid wage gains last year did not short-circuit the retreat in inflation because of the offset from strong productivity growth. That offset is not sustainable, as the productivity boost from the headline-grabbing AI technology is not expected to kick in for at least another year or two.

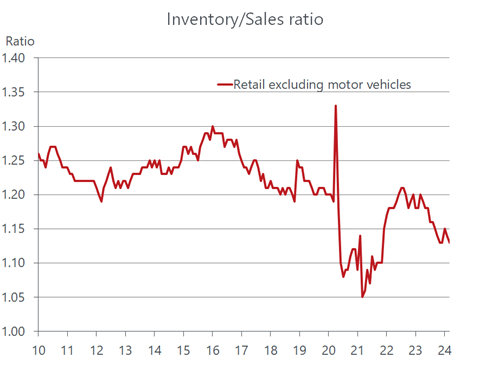

We expect job growth to continue to slow in coming months, thanks to softer demand and the reduced propensity of companies to hoard workers amidst a tapering off of profits. The nascent downshifting of the job-creating engine last month may be a sign that the lagged effects of the Fed’s restrictive policy are kicking in more forcefully. Keep in mind that just as high borrowing costs have a disproportionate impact on low-income households, they also harm small businesses more than large corporations that have access to the broader capital markets to finance operations. Small businesses, in turn, account for the bulk of job creation, including start-ups that rely heavily on credit cards and home equity loans, where rates have skyrocketed even as credit availability has become more restricted.

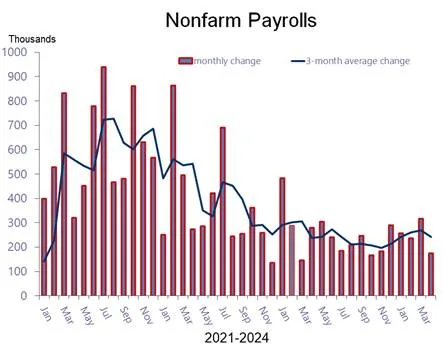

It’s possible that the financial restraints on small businesses have contributed to the inventory drag on GDP in the first quarter. Except for the pandemic related supply disruptions in 2020 and 2021, retailers, many of which fall in the mom-and-pop category, saw their inventories fall to historically low levels relative to sales in the first quarter. One reason could be that it has become prohibitively expensive to keep merchandise on shelves. According to the latest Fed data, the net percentage of banks increasing spreads on loan rates to small businesses over their cost of funds is at recession levels, topped only during the Great Financial Crisis.

Meanwhile, small businesses are paying the price. According to the National Association of Independent businesses (NFIB), borrowing costs on loans to these firms have risen sharply since the Fed paused its rate-hiking campaign last July. Since then, market rates have hardly budged while the actual rate paid by small businesses has increased by 1.3 percentage points. Ironically, the reluctance of these firms to stockpile inventory may be contributing to higher prices than otherwise, as demand for goods has held up surprisingly well over the past year, reflecting the shift towards remote working at home. In a narrow sense, therefore, a Fed rate cut that would help small businesses finance a higher level of inventories, and boost the supply of goods, would contribute to the Fed’s inflation-fighting efforts.