The good news is bad news narrative roiled the financial markets this week. It’s no secret that traders are looking for signs that the economy is cooling off, taking the heat off inflation and providing the Fed with the necessary incentive to start cutting interest rates. While the ingredients for this scenario fell into place late last year, they have appeared on and off over the first four months of this year, launching a roller coaster ride for stocks and bonds. This week was no exception. To be sure, the odds are still in favor of a Fed rate cut before the end of the year. But incoming data and signals from the Fed indicate that those odds are becoming slimmer by the week.

A glimmer of hope was provided by the April consumer price report released last week, which did not surprise on the upside for the first time this year. But the optimism that report fueled fizzled this week for a number of reasons. First the release of the minutes of the last policy-setting meeting revealed that not all Fed officials are on board for a rate cut, with some suggesting that policy may not even be restrictive enough to wrestle inflation down to the 2 percent target. Most other officials were not as hawkish and still believed that the next move in rates would be down, not up. However, they expressed uncertainty over the timing, leaving the impression that rates would stay higher for longer a sign that traders viewed as meaning no rate cuts this year.

We still believe that a September rate cut is on the table but, like the Fed, would like to see more evidence that inflationary pressures are easing. Not only was this week’s light calendar of data a mixed bag, it reflected the uneven impact that the elevated level of rates is having on the economy. The “good news” that sent stock prices reeling on Thursday and bond yields sharply higher was a report from S&P global that its PMI index of economic activity in the U.S. came in much stronger than expected. The report was released on the heels of the FOMC minutes, which hardly instilled confidence that high interest rates were doing the job or that the Fed had any incentive to cut rates anytime soon. Adding fuel to the “good news” narrative is that the labor market shows no sign of rolling over.

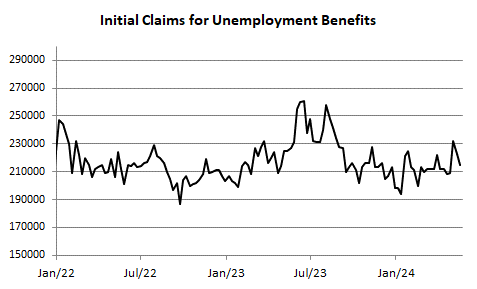

The 8,000 decline in initial jobless claims to 215,000 last week was better than the little change anticipated by Wall Street. After spiking to 232,000 a few weeks ago, thanks to a jump in claims in New York State linked to the timing of spring break, claims are now in line with the 213,000 average seen since the beginning of the year. The low level of jobless claims underlines the continued strength of the labor market, which is still characterized by very few layoffs. The volatility in initial jobless claims due to the timing of school spring breaks is now firmly in the rear-view mirror. Simply put, companies are continuing to hoard labor even amid signs of slowing sales and revenues. Until – and if – employers get over their fear of labor shortages that would hobble rehiring efforts during the next upturn in activity, the job market is not about to roll over, or lead the economy into a recession.

That said, households are not as confident that the job market will remain as sturdy in the months ahead. Indeed, growing job insecurity was evident in the May sentiment reading released by the University of Michigan on Friday. While the headline index was revised slightly higher than the preliminary reading released early in the month, that probably reflected the easing of gas prices and a strong stock market rally over the final weeks of the month. Importantly, Consumers have become increasingly concerned over the labor market and persistently high interest rates, with the press release highlighting that consumers expect a rise in the unemployment rate and for income growth to slow. While the labor market has remained resilient, consumers’ worsening outlook combined with the weaker pace of payroll gains and slower wage growth seen in April, could indicate that a slowdown in the labor market is beginning to take hold. Unsurprisingly, given their pessimistic outlook for jobs, households are also lowering their inflation expectations, something that should cheer the rate-cutting crowd.

And while the broader economy is holding up well under the Fed’s persistent foot on the brake, that’s not the case for the most rate-sensitive sector of the economy: housing. Sales of both existing and new homes took a step back in April, as high mortgage rates and home prices are taking a toll on affordability. Mortgage rates climbed over 7 percent in April for the first time this year, which undoubtedly clipped sales of new homes, as these represent contracts signed at current rates during the month. Resales of existing homes, however, are based on contracts signed two or three months ago, when mortgage rates were lower, but not by much. Not only are high mortgage rates discouraging sales, it also limits supply by discouraging homeowners from putting their homes on the market and giving up their low-rate mortgages. In April, the supply of existing homes did increase slightly, but inventories are still skimpy and would sell out in 3.5 months at the current sales rate. A more balanced market would consist of a 6-month supply.

The limited supply of existing homes on the market is giving homebuilders a boost, as sales of new homes have held up somewhat better this year. Prices on new homes are higher than on existing homes, but the premium has narrowed as builders are constructing smaller, less expensive, homes and offering incentives to lure new home buyers, such as credits for closing costs and mortgage-rate buydowns. Still, the supply of homes for sale increased 2.1% in April to 480,000 units, the most since January 2008. The available inventory translated into 9.1 months of supply at the April selling pace, up from 8.5 months in March. As noted, six months of supply is generally considered to be consistent with a balanced housing market but given the relative scarcity of existing homes for sale, despite recent increases, we do not think the supply of new homes for sale is a cause for concern. A smaller share of new-home inventory is completed than in times past, and builders have little to fear of the length of time newly built homes will sit on the market. It is only taking about 2.5 months after completion for builders to sell new homes, down from the pre-pandemic average of 5.2 months.

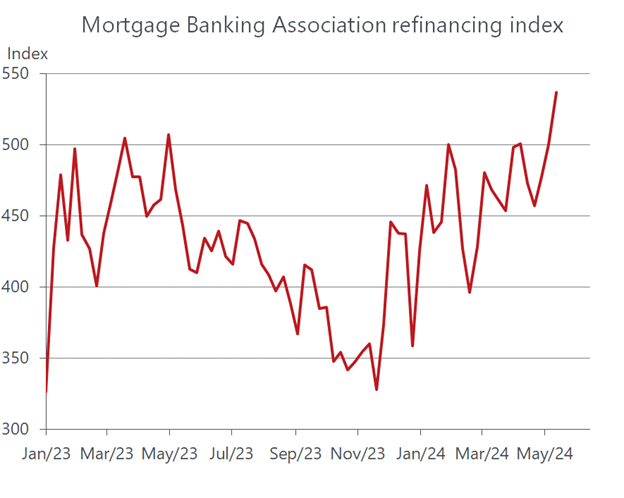

Although mortgage rates slipped below 7 percent in the latest week, at 6.94 percent it still stands higher than most anytime this year prior to April. But while that may be discouraging sales, it has not prevented a surprising burst in refinancing activity, which in the latest week climbed to the highest level since September 2022. It’s unclear what is motivating homeowners to tap into their housing equity so copiously. For sure, the surge in home prices in recent years has generated a hefty equity cushion, reinforcing the gains in stock portfolios that has lifted household net worth. If homeowners are feeling wealthier and are cashing out some of their housing equity to bolster discretionary spending, that augurs well for the economy.

However, there may be a more dispiriting explanation for this development. Rather than cashing out their equity for nonessential purposes, homeowners may be using these funds to pay down their burgeoning credit card and auto loan debt that carry interest rates far above 7 percent mortgage rates. It may also be a sign that they have run out of savings and reached their limit on credit card borrowing, leaving home-equity credit as an only alternative to obtain liquidity for day-to-day living. That alternative explanation would be a bad sign for the economy, as it points to weaker consumer spending. Time will tell, but a combination of slowing job gains and wage growth that we expect in coming months alongside growing debt burdens indicates that consumers will be turning more frugal later this year. That, in turn, should lead to easing inflation pressures and set the stage for the Federal Reserve to start cutting rates by the fall.