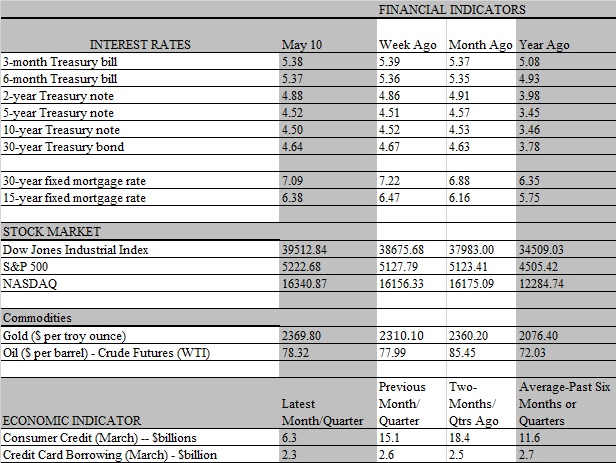

The data-dependent Federal Reserve had little of substance to digest this week, as the economic calendar was very light. It will be another week or two before the next round of key data either nourishes or dilutes the budding narrative of a slowing economy instigated by the April jobs report. We suspect that support for the slowing case will be forthcoming, but a corresponding improvement in the inflation dynamic may take a while longer. Hence, the Fed’s rate decision will become ever more complicated, something that is already showing up in comments by numerous Fed officials over the past week. The prevailing sentiment presented by Fed Chair Powell two weeks ago is that it is taking longer to reach the 2 percent inflation target than expected, but the Fed is still closer to cutting rates than hiking them. Just how close, however, is the question, as some Fed officials are hinting that the starting date may be pushed back into next year. Dallas Fed president Lorie Logan on Friday speculated whether policy is restrictive enough to tame inflation.

A lot, of course, will depend on how rapidly the economy and job market cools. If the slowdown becomes sharper, the Fed’s focus will likely tilt towards staving off a recession than fighting the slow progress in reaching the 2 percent inflation target. Unsurprisingly, signs of softer economic activity in recent weeks have imparted a positive jolt into the financial markets. What’s more, the impulse is amplified by incoming profits reports that are beating expectations. The combination of sturdy profits amid slowing growth suggests that productivity gains are still offsetting elevated labor costs, as price increases, while not slowing, are not accelerating. That said, companies are clearly turning their attention towards controlling labor costs, as the prospect of weaker demand threatens revenue streams while the productivity surge over the past year is not sustainable.

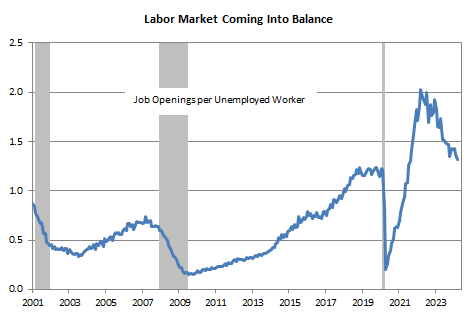

Some signs of labor cost control are becoming increasingly visible. The most impactful on the financial markets came from the slowdown in job growth revealed in the April employment report. That headline-grabbing news followed an equally significant retreat in job openings in March revealed in the preceding JOLTs report issued by the Labor Department. That 325 thousand decline in job postings, in turn, raised hopes that cooling labor conditions would be accomplished by reduced hirings rather than increased layoffs. We believe that a rebalancing of the demand for and supply of labor is unfolding, but historically, labor conditions have rarely followed a smooth line towards stability. When the job market turns sour, it usually gains traction swiftly before remedial actions by policymakers can stop it.

That’s why it’s imperative for the Fed to get the timing of rate cuts right. Some officials, most recently the aforementioned Logan, are concerned that the economy has not buckled enough under the current level of rates to bring inflation down. Others have faith that the lagged effects of high rates, while taking longer to kick in, will soon bring about the desired result, with sufficient progress being seen before the end of the year. Traders are fickle and respond on the dime to incoming data. Until the latest data on the job market, they pushed back the timing of the first rate cut to December. Over the past two weeks, however, this hawkish sentiment has melted, as the markets are pricing in a 75 percent chance that a cut will take place at the September meeting.

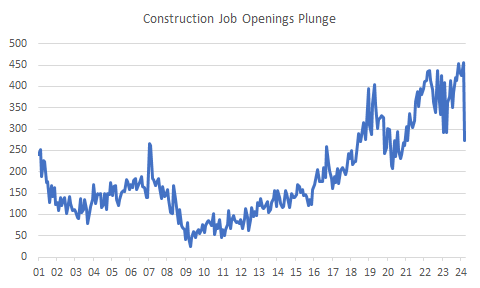

We caution, however, that the markets have raced ahead of reality several times since late last year, and it would be a mistake to put too much confidence on the latest bet. Still, it would also be a mistake to ignore recent signs that the lagged effects of the steep rate hikes in 2022 and 2023 are kicking in. For example, residential construction, one of the most rate-sensitive sectors of the economy, has held up quite well as the limited supply of homes in the resale market has spurred a surge in homebuilding activity, and construction jobs. But with mortgage rates spiking above 7 percent, that is poised to change. Indeed, job openings in the construction sector suffered the biggest drop on record in March and accounted for more than 50 percent of the decline in total listings. That hasn’t translated into job losses yet, but the 9 thousand increase in construction payrolls in April was the smallest in more than a year and is less than one-third of the 30 thousand average monthly increase during the first quarter. The setback may be a one-month fluke, reflecting adverse weather conditions, but is something that needs to be followed closely, as a homebuilding downturn is a time-honored precursor of recessions.

To make matters worse, the spike in mortgage rates to over 7 percent is short-circuiting a nascent rise in homes for sale in the resale market that had been underway. More recently, homeowners have pulled their homes off the market because it would be too expensive to trade up to a more expensive home and give up the low rate they owe on their existing mortgage. That change in behavior only worsens the shortage of available supply and further drives up home prices, shunting a broader swath of potential buyers out of the market, particularly those seeking to purchase their first homes. These discouraged buyers, meanwhile, are forced to either double up with families, or return to renting, which, for lower-income households, is taking an ever-larger bite out of budgets.

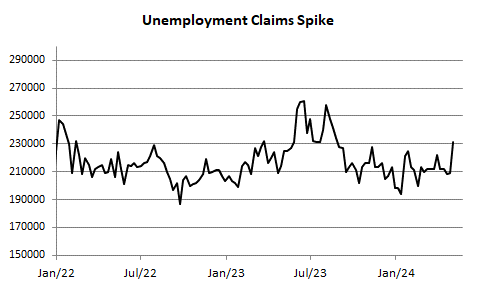

Needless to say, the budgetary squeeze on households living paycheck to paycheck would become dire if employers decided to stop hoarding workers and purge workers from payrolls in the face of weaker sales, which may have been signaled by the weak March retail sales report. So far, that has not been the case, as companies are continuing to add to staff at a healthy, if slower, pace. But a cautionary note was sounded in the labor market this week, as initial claims for unemployment benefits jumped by 22 thousand to the highest level since last August. In the wake of the decline in job openings and the slowdown in payroll growth in April, that surprising addition to the unemployment lines could be a worrying sign that the labor market is poised to fall off a cliff. Some believe that laid-off hi-tech workers with huge severance packages are belatedly filing claims as job opportunities in this sector are drying up.

However, at this point we would not place much importance on a one week jump in claims. The jump appears to be an outlier, with much of the increase driven by a spike in New York. That could be linked to school recess not being adequately captured by the seasonal adjustment process, with short-lived spikes in claims a recurring feature this time of year in that state. We suspect that fillings will drop back down in next week’s report. But even if it remains somewhat elevated, it does not mean that the job market is sinking into recessionary territory. We estimate that the break-even level of initial claims ” the level that would be consistent with no job growth ” is roughly 260 thousand, and the four-week average of claims, at 215 thousand, remains comfortably below that level.

Simply put, the Fed likely welcomes evidence of a further loosening in labor market conditions, which will contribute to slowing in wage growth and inflation. Unless the labor market weakens substantially, which we don’t expect, changes in Fed policy will be determined almost exclusively by readings on inflation. We think the Fed needs to see a string of reports showing inflation is heading back to a sustainable path toward 2% before lowering interest rates. All eyes will be on next week’s slew of economic reports, which will include a key update on inflation. Unfortunately, the April reading on consumer prices will probably not sit well with the Fed, as the headline CPI is expected to be boosted by higher gasoline and used car prices. However, the trend should become more favorable in coming months and we suspect that by September enough progress on the inflation front will have occurred to allow the Fed to execute its first rate cut of an easing cycle that should extend into next year.