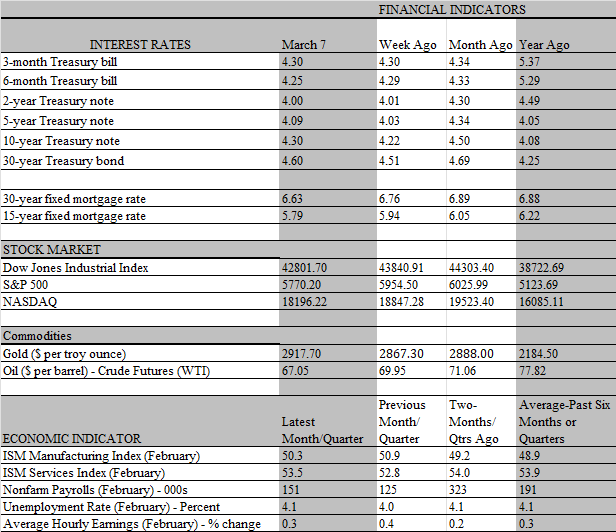

Amid the chaos surrounding the Trump administrations on-again, off-again tariffs the job market sounded a calming note this week. For one, there were no signs of employer panic over trade uncertainty and incipient recession fears that resonated though Wall Street over the past several weeks. Yes, the outplacement firm, Challenger, Gray, reported that a huge 173 thousand workers were laid off in February, the highest monthly total since July 2020, when Covid was still wreaking havoc with the job market. But that hardly made a dent in the official unemployment rate, which the Labor Department revealed inched up 0.1 percent to 4.1 percent during the month on Friday. The unemployment rate has remained firmly within the 3.9-4.2 percent range in every month over the past year.

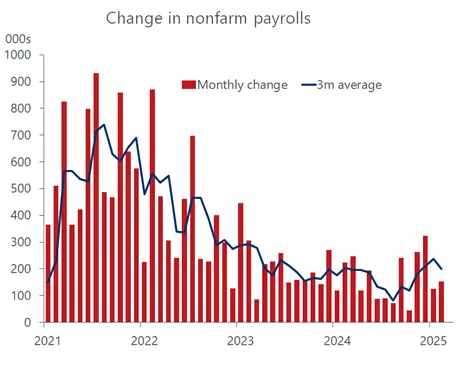

Nor did employers stop adding to payrolls last month. The employment report released on Friday was nothing if not more of the same that we’ve seen over the past year. Job growth is gradually slowing, not falling off a cliff. Companies added 151 thousand jobs in February, a touch weaker than the consensus forecast of a 160 thousand gain. Revisions for the previous two months were mostly a wash, as the January gain of 143 thousand was revised down to 125 thousand while the December increase was revised up to 323 thousand from 307 thousand, leaving a net 2 thousand reduction for the two months. The three-moving average of job gains slowed to 200 thousand from 236 thousand in January. That’s well above the so-called breakeven rate, namely the amount of job growth needed to keep the unemployment rate stable. However, barring a surprise, that trend should downshift noticeably next month when the outsize December increase falls out of the calculation.

The important point to remember is that the latest jobs report derives from a survey that covers the February 12 week. Hence, it essentially tells us what happened over the first half of the month when the Trump administration was in office for only a few weeks and its policies on tariffs, DOGE layoffs and immigration were just being rolled out. The reverberations from those policies should start to show up in the data next month. Even then, the numbers will not tell the whole story. For example, it is estimated that about 80 thousand Federal workers have been purged from government jobs but will still be paid through the fall. As long as they are paid, they will be counted as employed and, hence, will not boost the unemployment rate.

That said, there are some soft spots in the February jobs report that may be a precursor of what lies ahead. The number of workers putting in fewer hours than they would like the so-called involuntary part-timers surged by 460 thousand, which, except for one month in June of 2023 was the largest monthly spike since the Covid recession in April 2020. The monthly data can be noisy, so it would be a mistake to put too much emphasis on the February surge. But if you add those workers to others who dropped out of the labor force but would take a job if available, as well as those officially counted as unemployed, the picture looks a bit more dire. That broader group, captured by the Labor Departments broader U-6 underemployment rate, rose 0.5 percent to 8.0 percent in February, the highest since October 2021.

What’s more, the rise in involuntary part time work aligns with the weakening trend in the workweek. While the workweek held steady at 34.1 hours in February that’s below the average of the last couple of years of 34.3 hours. We thought the decline in hours worked in January would be temporary, related to harsh winter weather and the Los Angeles fires; if it remains at the February level it could be cause for concern. A decline in hours worked can be a precursor of rising layoffs in an uncertain economic environment. When conditions look shaky companies initially respond by cutting back worker hours before reducing headcount when the environment turns out to be fundamentally weaker.

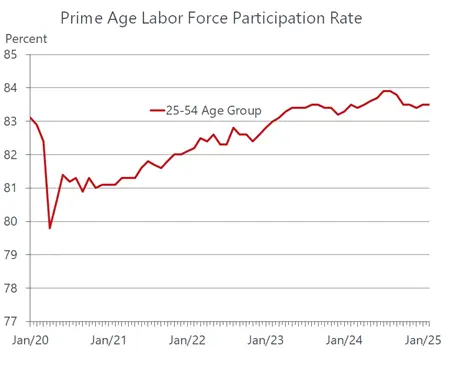

Other details of the jobs report present a mixed picture. The labor force participation rate slipped to a two-year low of 62.4 percent from 62.6 percent. But this is not overly concerning or unexpected as a secular decline due to demographic forces (an ageing population is spurring more retirements), a slowdown in net immigration, and a tapering off in labor demand linked to weaker growth are all underway. We expect those forces to continue to weigh on the share of adults in the labor force this year. But among prime age workers (between 25 and 54 years old), the participation rate is holding steady at a near-historical high of 83.5 percent. Thats the core of the labor force and is more representative of the health of the job market.

Critically, workers continue to enjoy a solid increase in wages. Average hourly earnings increased 0.3 percent, both for all private workers and those in nonmanagement positions. That translates into a 4 percent increase over the past year, which is comfortably above the 3 percent inflation rate, as tracked by the consumer price index. The ongoing increase in real incomes means that households still have the firepower to continue spending, injecting fuel into the economys growth engine. Importantly, the 4 percent annual increase in worker earnings is not inconsistent with the Fed 2 percent inflation target, as productivity growth is offsetting 2 percent of the rise in labor costs. If that productivity trend continues which we expect, thanks to the growing contribution of AI employers can give workers 4 percent pay raises and limit price increases to 2 percent without hurting the bottom line.

That means, of course, that the Federal Reserve can sit back and wait to see how things work out before making another change in interest rates. For sure, nothing will be done at the next meeting in less than 2 weeks. With the job market still churning out payrolls at a decent pace and consumer purchasing power intact, policymakers can continue to focus on keeping inflation in check by keeping rates where they are. They will not, however, be in a permanent holding pattern. Odds are, the February jobs report will be the high watermark for the foreseeable future, as the growth drag from tariffs, heightened uncertainty and Federal worker layoffs kick in. Keep in mind that while Federal workers comprise a small fraction of the overall labor force, there is a strong synergy between the government and the private sector. For every Federal worker that loses a job because of a government spending cutback, it is estimated that three in the private sector working for government contractors lose theirs.

The decent jobs report following a drumbeat of weak economic reports over the past three weeks has roiled the financial markets. For the most part, the weak data and prospective tariffs have had more of an impact on traders and investors, raising fears of a recession and sending market yields and stock prices decidedly lower. Market expectations regarding Fed policy have also shifted; until recently, with inflation ranking high the list of concerns, the belief was that the Fed would pause its rate-cutting campaign indefinitely, with some expecting the next move to be a rate increase. That hawkish perception has been downgraded in recent weeks, as expectations of three rate cuts this year have increased. From our lens, the Fed will be overseeing an economy that is slowing, but not recession prone. The first quarter will look dismal, with GDP growing at a sluggish pace of 1 percent or so, thanks to harsh weather and other temporary forces dampening activity, including the frontloading of imports to beat tariffs that has driven the trade deficit to record highs. However, we expect the economy to rebound over the rest of the year, enough to keep the Fed on the sidelines until more visible signs of slowing inflation reappears. We give very low odds of a rate increase, but do not expect the next cut to happen until the fall or winter.