A snapshot of Februarys incoming data paints a picture that is in stark contrast to evolving perceptions of the economy. Sentiment on Main Street and Wall Street has turned decidedly bearish, with fears of both recession and inflation garnering headlines. Yet most key reports for February portrayed an environment that is as close to Goldilocks as any scenario seen since the Covid downturn. Most notably, Inflation cooled even as the bedrock of growth, the job market, turned stronger. Despite the encouraging hard data, consumer and business confidence is sinking, stock prices have dipped into correction territory before rebounding on Friday and bond yields have increased.

It’s not the first time that hard and soft data have conflicted, and it almost surely won’t be the last. A respite from the negative headlines appeared on Friday, as the Senate is poised to approve the Republican funding bill, thus avoiding a government shutdown that would likely have reinforced the bearish sentiment on Wall Street. But the ever-escalating trade wars show no sign of ending and their ramifications for growth and inflation over the near term remain more negative than positive. This, in turn, heightens the challenge facing the Fed, as both sides of its dual mandate are threatened. Odds are the good news revealed in the hard data last month will dissipate in the coming round of reports. It’s important to remember that the impact of Trump’s tariffs and attention-grabbing Federal cutbacks were not captured in the February data.

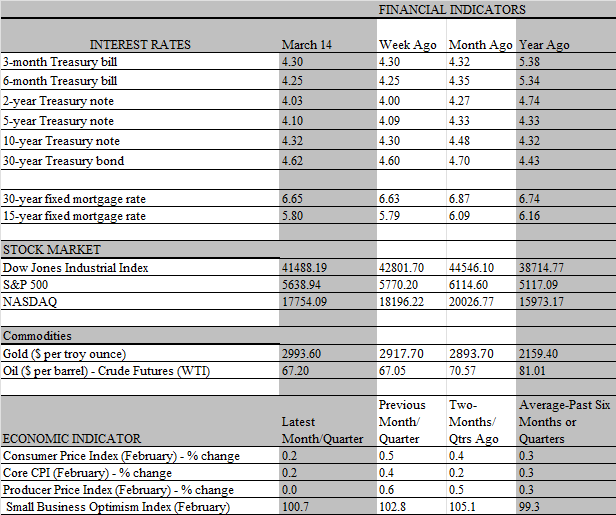

That said, the Fed is data driven, and the most recent employment and inflation reports point to a stand-pat policy at least over the foreseeable future. The job market remains on a solid footing, underpinned by healthy increases in nonfarm payrolls and earnings in February, while layoffs remained low through early March. Importantly, labor’s solid underpinnings are not a source of upward price pressures. As revealed this week, consumer prices increased at a slower pace than expected in February with the not-so-terrible 2s dominating the consumer price report. Just about every key category increased 0.2 percent last month, including the overall CPI, the core CPI, energy and even food prices, notwithstanding the 10.4 percent jump in egg prices. The consensus forecast was closer to 0.3 percent for most of these categories. Importantly, core service prices excluding shelter, the supercore index the Fed closely monitors, also rose 0.2 percent and housing costs are cooling.

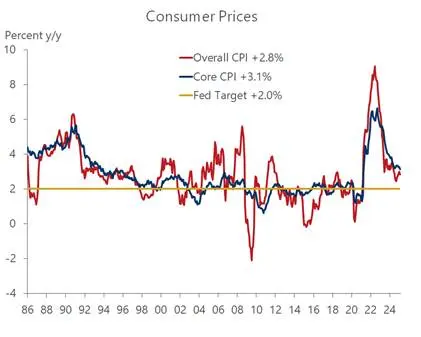

The slowdown from January to February also sliced the inflation rate over the past year, to 2.8 percent from 3.0 percent for the overall CPI and to 3.1 percent from 3.3 percent for the core CPI. Both were cooler than expected and suggest that the stalled disinflation trend has resumed. But that’s not how it is perceived in the real world where inflation expectations have jumped sharply, thanks largely to the prospect of higher tariffs. That was dramatically revealed in the household survey for early March by the University of Michigan released on Friday morning. Both short and long-term inflation expectations surged, with the long-term outlook soaring from 3.5 percent to 3.9 percent, the highest reading since February 1993. Equally distressing and making life harder for the Fed is that households turned considerably more pessimistic, with the overall sentiment index plunging 11 percent, the third consecutive monthly decline.

To be sure, the link between consumer sentiment and behavior has weakened in recent years and policymakers are more concerned with what consumers do than with how they feel. Household sentiment sank to a record low in mid-2022 amid spiraling inflation yet continued to spend at a healthy pace throughout the year. At this juncture, we sense that the Fed is more worried over the possibility that long-term inflation expectations become unanchored, leading to a self-fulfilling prophecy that would be difficult to arrest. That concern leads us to believe the Fed will keep its policy rate at current levels at least through December, although the financial markets are pricing in as many as three cuts this year.

Key to the outlook is our belief that consumers will behave more aggressively than they feel. For one, workers are more than keeping up with inflation. Thanks to another solid increase in earnings last month combined with cooler inflation, real earnings continue to increase at a sturdy pace. For another, household balance sheets are healthy, particularly among the upper-income cohort that benefited from appreciating asset values in recent years and accounts for the lions share of aggregate consumption. One caveat is that the wealth effect could well turn negative if a bear market sets in. The slump in stock prices until Friday’s bounce reflects the markets vulnerability to the heightened uncertainty linked to the erratic trade policy currently unfolding.

It remains to be seen if the stock market rally on Friday is sustained or simply a temporary reaction to the likely passage of a government funding bill that averts a shutdown. Clearly, investors are nervous that the tariff wars will escalate, threatening to do serious damage to the economy, not just to sentiment. President Trump suggested in recent comments that he is willing to accept short-term economic pain, even a recession, to achieve his longer-term goals. Some commentators note that behind this thinking is the notion that it is better to absorb the pain early so that a recovery is well underway leading up to the mid-term elections. However, that logic would have more validity if there were serious imbalances in the economy that needed to be purged. No such condition is glaringly present now, unless the historically high budget deficit is considered to be one. �However, it is unclear how a recession would help solve that issue.

The Fed is not expected to make any rate changes at next weeks policy meeting, but all eyes will focus on the retail sales report for February. That should provide an early indication of how consumers are reacting to the drumbeat of tariff news. We expect some rebound from the weather induced weakness in January and, perhaps, some purchases being pulled forward to beat price hikes related to tariffs. Uncertainty is a dark cloud hanging over the economy, and it will likely persist because of the Trump administrations approach to tariffs and fiscal policy. Unlike bouts of heighten monetary policy uncertainty, the Fed can’t fix this. The central bank is in the same boat as businesses and financial markets because it doesn’t know what lies ahead for tariffs or fiscal policy, a reason the Fed feels safest on the sidelines and why we don’t expect a rate cut to occur until December. However, any unexpected weakness in retail sales might soften the Fed’s commitment to keep rates restrictive.