There will be no commentary over the July 4 holiday. The next weekly will be published on July 11.

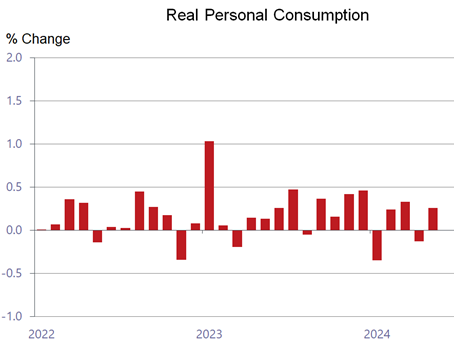

Once again, reports on the death of consumer spending are premature. After showing signs of fatigue in recent months consumers snapped back to life in May, overshadowing the soft retail sales report released last week. Since consumers are the economy’s main growth driver, their resilience is stark evidence that recession fears are unfounded over the near term. To be sure, just as the weakness shown in previous months was not the start of a downward spiral, it would be a mistake to view the rebound in May as a sign that consumers are off to the races. If nothing else, the erratic monthly behavior of the data makes it difficult to discern an underlying trend.

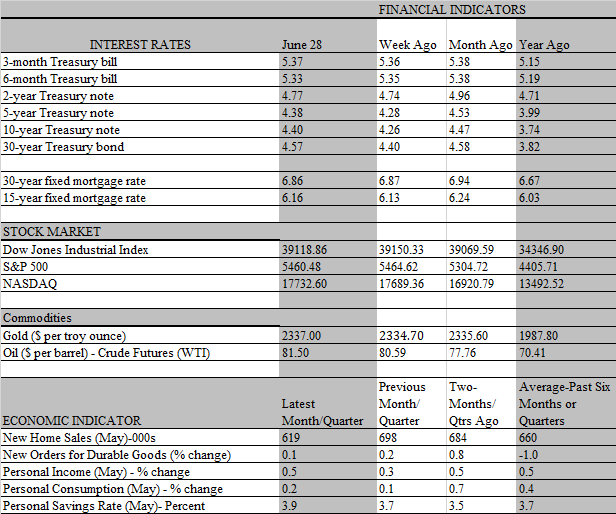

That said, the supporting details in the latest personal income and spending report makes it hard to believe that households are poised to zip up their wallets. Much has been made of the strong balance sheets of households that constitutes a formidable buffer against a softening job market. No doubt, the surge in housing equity and burgeoning stock portfolios has underpinned a wealth effect, encouraging households to save less and spend more out of incomes than otherwise. But it is not easy to convert asset-based wealth into spendable funds, which is why income growth is key to sustain spending habits. In May that condition was more than satisfied, as wages and salaries leaped by 0.7 percent, matching the strongest monthly gain since January 2023, contributing to a sturdy 0.5 percent increase in overall personal incomes. After taxes and inflation, the increase was just as impressive, as real disposable income also recorded a 0.5 percent gain, rebounding from no change in April.

Armed with this infusion of spendable funds, households stepped up outlays on goods and services, lifting real consumption by 0.3 percent, more than reversing the -0.1 setback in April. Households still had more funds left over from the income gain, and hence were able to pad their savings accounts, lifting the savings rate from 3.7% to 3.9%. That, in turn, should fortify them with more spendable funds to keep their wallets open and the economy afloat for the foreseeable future. Interestingly, the spending rebound last month was mostly for goods, as real spending on services barely increased, posting the weakest reading since last August. That divergence is at odds with the ongoing narrative that spending on experiences is the driving force behind consumption, as households have more than satiated their demand for goods during the lockdown period.

It appears, however, that remote work is sustaining the demand for goods even as a broad swath of products is becoming cheaper, reflecting ongoing deflation in goods prices. The setback in service spending also raises questions about another narrative, that upper income households who account for 80 percent of consumption have enough firepower to drive the economy. This cohort benefited the most from the wealth gains in recent years, as they hold most of the financial assets that have appreciated in value, bloating their portfolios. They also have more discretionary funds that fuels spending on many services, concerts, sporting events, cruise ship vacations and luxury hotels, all of which are booming, reflecting their higher incomes as well as the revenue derived from financial assets.

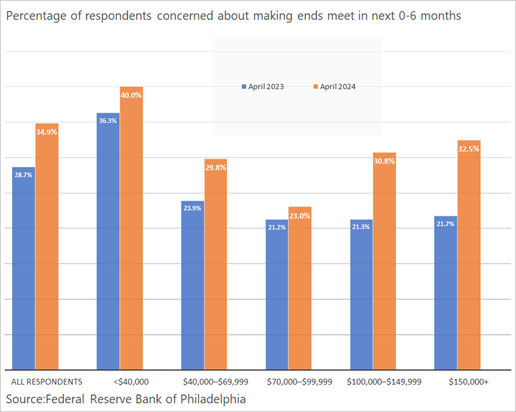

That combination of wealth and income should, on paper, underpin a sense of confident well-being, not the financial strains that lower income individuals are coping with, including falling behind on credit card payments. However, that might not be the case. At least one recent survey suggests that financial strains are becoming more intense for upper income households than those further down the income ladder. The Philadelphia Federal Reserve Bank just released a survey that shows people with an annual income of more than $100 thousand are having more trouble meeting expenses over the next six months than lower-income individuals compared to a year ago. Unsurprisingly, those earning less than $40 thousand a year are suffering the harshest budget squeeze, with 40 percent reporting that they are having trouble making ends meet. But that cohort is usually under more stress than others, and the severity of their plight has only increased by 3.7 percent over the past year. The highest income earners, however, have seen their financial struggles increase by a whopping 10.8 percent and the 32.5% share that reported an inability to make ends meet over the next six months is higher than the three income groups just below them.

To be sure, this is one survey among many others that constitute a basket of soft data, which overall depicts a weaker economy than the hard data. But the biggest drags on the other surveys, most notably the consumer confidence surveys, stem from the gloomier mindset of lower income households, so this is either an outlier or something that bears watching more closely. A disconnect between hard and soft data is not uncommon. Importantly, when the Federal Reserve asserts that its policy decisions are data dependent – as is currently the case – it is influenced more by the hard than the soft data. The mantra watch what people do not what they say is the governing influence. Still, there is evidence that soft data have more predictive value around cyclical turning points, so these surveys do matter.

Unsurprisingly, the week’s key income and spending report bolsters two notions held by us as well as the market consensus. One is that the economy is skirting a recession, despite the Fed’s historic rate hikes, and has a better chance of gliding into a soft landing than thought earlier this year. Second, the Fed is more likely to cut rates two times this year rather than the one signaled at its last policy meeting in June. Recession fears that gained some traction during the spring as consumers pulled back are now on the back burner as the May data shows that personal consumption is back on track. Downward revisions to spending in March and April points to less momentum entering the second quarter – which will curb growth for the period – but building momentum as the quarter progresses. Unless the job market falls off a cliff, which we do not expect, the stage is set for consumers to keep the economy on a modest growth path for the remainder of the year.

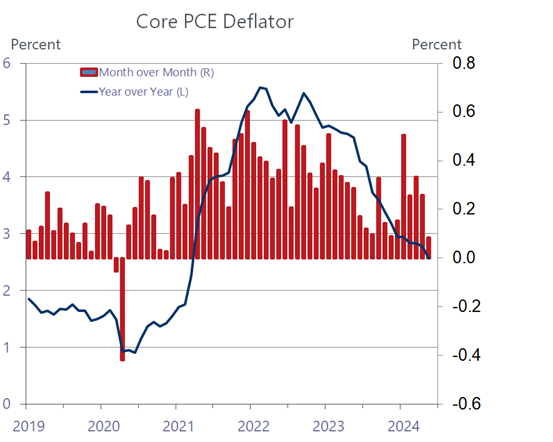

The second leg of a soft landing involves the continued retreat in inflation amid a still-growing economy. That too was confirmed in the income and spending report, setting the stage for the Fed to cut rates sooner rather than later. The key inflation measures that the Fed monitors avoided a dreaded upside surprise and came in just as expected, continuing the slow but steady easing trend towards the 2 percent target. The headline personal consumption deflator was unchanged in May, and the core PCE increased by a slim 0.1 percent, the slowest since November 2020. The increase in both measures ticked down to 2.6 percent from a year ago. Sticky housing costs are slowing the descent, but most other prices are complying. The so-car supercore inflation ( core PCE excluding housing costs ) that the Fed closely monitors edged up by only 0.1 percent in May, the slowest since last August.

The road to 2 percent will be bumpy but should arrive by next year. Importantly, the Fed will not wait for inflation to recede all the way down to that target, only that the trend towards it is sustainable. If it waits until the final destination is reached, it will fall behind the curve and be too late to keep the economy out of a recession. Fed officials are aware of that risk and should be ready to pull the preemptive rate-cutting trigger at the September meeting. We expect two cuts this year and a reduction in every other meeting next year as inflation descends ever closer to the 2 percent target and the need for debt relief among lower-income households becomes more urgent.