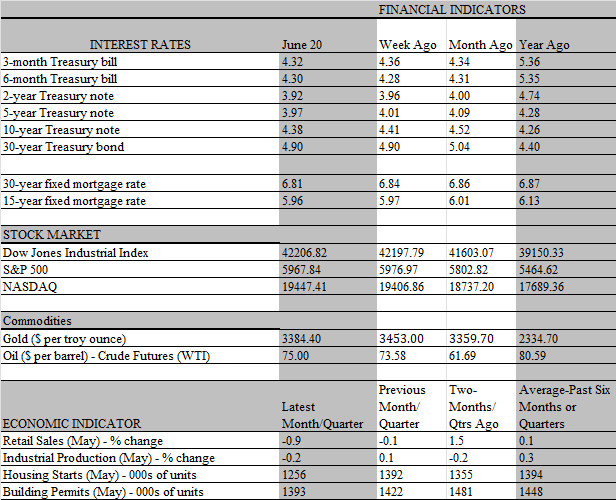

The Federal Reserve’s policy meeting this week yielded more questions than answers for the market to digest. As expected, rates were kept unchanged for the fourth consecutive meeting, leaving the federal funds rate at 4.25-4.50 percent. Also, as expected, the median rate forecast of the 19 members of the policy-setting committee remained unchanged from March, pointing to two rate cuts over the final four meetings of the year. But more officials than last time expect fewer cuts, and one expects the Fed to keep rates unchanged IN 2026. Simply put, the headline suggested the Fed retained a dovish outlook for rates, but behind the scenes that sentiment was more fractured than firm. That said, there was little opposition to retaining a “wait-and-see” strategy, given the fog of uncertainty over how government policies will play out and the crosscurrents seen in incoming data.

Much of Chair Powell’s post-meeting press conference was devoted to questions around tariffs and their inflationary implications. Like everyone else, Powell could not provide definitive answers as to how the biggest tariff upheaval seen in nearly a century would impact inflation or the economy’s growth engine. The updated Summary of Economic Projections straddled the line, indicating that both sides of the ledger would be negatively affected. Compared to the previous SEP presented in March, growth and employment are expected to weaken, and inflation to be higher. The Fed’s biggest nightmare, of course, is dealing with stagflation, which presents it with a possible no-win situation of choosing between least worst alternatives – fighting inflation or rising unemployment.

By keeping rates unchanged at modestly restrictive levels, the Fed is implicitly choosing the former – for now. No doubt, the scars from downplaying the post-covid inflation spiral – calling it “transitory” – is fresh in mind and discouraging a premature move towards a rate cut, much to the displeasure of President Trump. Whether that is the case or not, we believe it is the correct decision given the economic backdrop. The economy is not on the cusp of falling off a cliff, workers are holding on to their jobs and incomes are outpacing inflation, supporting purchasing power and, hence, spending. Given these conditions, the urgency for a rate cut is hard to see.

But the Fed also has a history of overstaying a policy stance, relying on backward- looking data that leads it down the wrong path. We don’t see that as an ominous portent now but recognize that there are cracks in the pillars undergirding the economy’s health. The job market continues to exhibit traditional measures of strength, with the unemployment rate hovering near historic lows at 4.2 percent and, as noted, generating solid gains in worker pay. Those measures, however, mask some pockets of weakness. The unemployment rate is being held down by the slower growth in the labor force, in part due to fewer immigrants entering the labor market, and the hoarding of workers by businesses, fearing rehiring difficulties if future sales hold up better than expected.

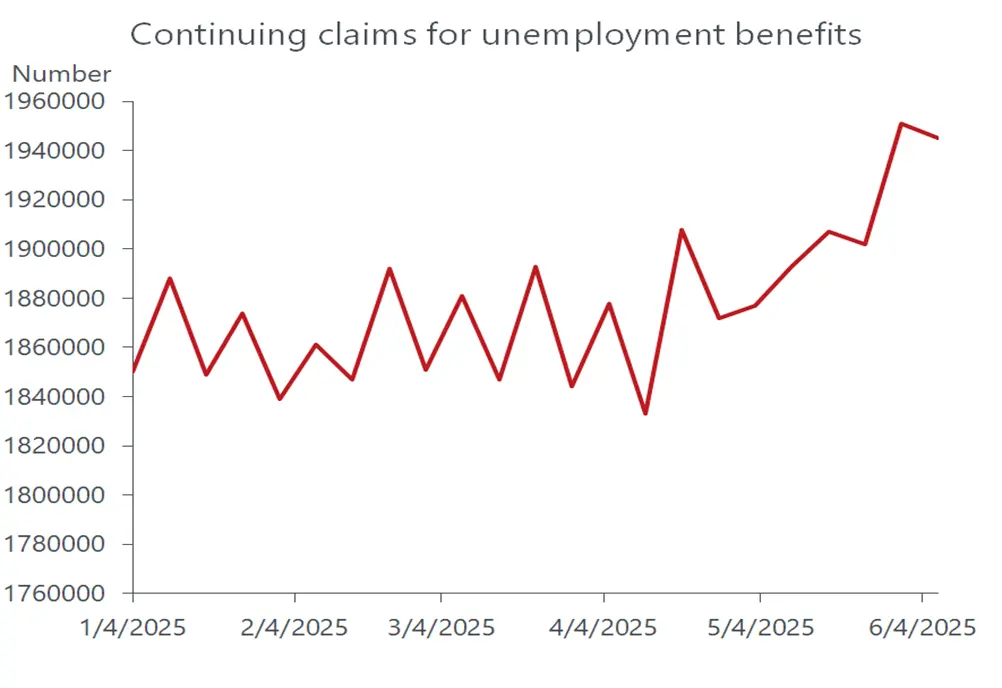

But hiring has also slowed and the “no hire, no fire” strategy is extending the time that job seekers are staying on the unemployment lines. While initial claims for unemployment benefits are slowly, but steadily, rising, continuing claims are climbing at a more alarming pace. This is seeping into the mindset of jobholders, who are less inclined to jump ship for a better paying position. Hence, a lower hiring rate is being joined at the hip with a lower quit rate. That’s a time-honored combination pointing to weaker labor bargaining power – and slower wage gains. When that occurs, the lowest paid workers are usually the most vulnerable, and that seems to be the case unfolding now. According to the Atlanta Fed wage tracker, wages in the lowest quartile have increased 3.8 percent over the past year through May compared to 4.4 percent for all workers. That 0.6 percent shortfall is the largest since 2014.

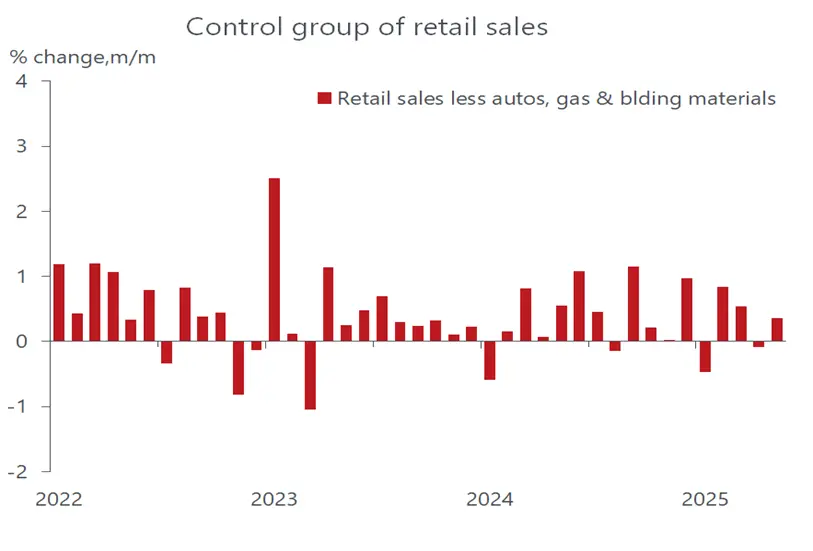

Still, even at 3.8 percent the lowest paid cohort is staying ahead of inflation, and there is little sign that consumer spending is rolling over. True, retail sales in May slipped by a larger than expected 0.9 percent, but that follows a shopping spree earlier in the year as consumers front-loaded their purchases to beat tariff-induced price increases. Big-ticket purchases, notably motor vehicles, were the biggest swing factor boosting then dragging down overall sales, while lower prices at the pump weighed on gasoline sales. Importantly, the control group of sales, which feeds into consumer spending in the GDP calculation, staged a solid 0.4 percent increase in May. That should give heft to the economy’s main growth driver in the second quarter, as personal consumption is tracking a sturdy 2.0 percent growth rate for the period.

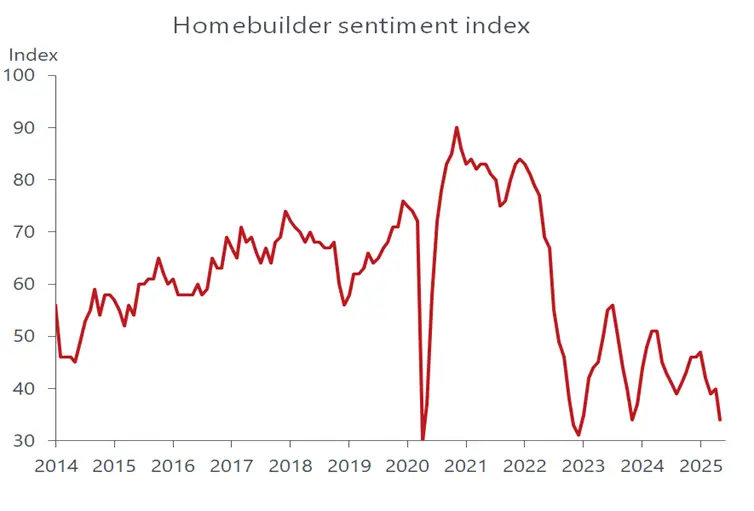

But the Fed should be mindful that rate-sensitive sectors of the economy are feeling some pain. The poster child among the victims of high interest rates is the residential sector, which has been under pressure for some time. Next to autos, sales of building materials posted the largest sales decline in May. But that followed two monthly increases, so a downward trend has yet to be established. That’s not the case for the broader homebuilding industry, which has been on a persistent downward trajectory that shows no sign of ending. Only once since the Covid recession in 2020 has homebuilder sentiment been as low as it is now.

Unsurprisingly, residential construction is slumping badly. Housing starts plunged nearly 10 percent in May to the lowest annual rate since May 2020. The volatile multifamily sector took the brunt of the fall this time, but single-family construction is down 14.2 percent from the end of last year. Prospects for single-family construction looks grim, as building permits have fallen in four of the past five months and are down by more than 9 percent since December. While high interest rates are a major cause of housing weakness, other influences play a key role, including construction costs, the availability of construction workers and affordability. All these influences are weighing on the sector, and tariffs along with immigration policies are exacerbating the problem.

Residential construction outlays only account for about 5 percent of GDP but they have broader implications for the economy, influencing spending on furnishings, appliances, electronics, moving expenses among many other goods and services. Unsurprisingly, housing activity is one of the more consistent leading indicators of a recession. We suspect that towards the end of the year the combination of high interest rates and tariffs will take more of a toll on the economy and coax the Fed over to the dovish side. Assuming the inflation impact from tariffs is not persistent, it should start cutting rates by the last meeting of the year in December.