The Federal Reserve has long insisted that its policy decisions are data dependent, not forecast dependent. For the most part, the mix of data since it paused the rate-cutting campaign in January has justified that strategy. The economy has held up well, with unemployment hovering around historical lows, at 4.2 percent, while inflation has remained stubbornly above the 2 percent target. But recent data has seen a steady shift in the mix, with the economy showing increasing signs of softness even as inflation has turned considerably cooler. On the surface, that would suggest policymakers are poised to resume the rate-cutting campaign sooner rather than later. Yet, neither comments by Fed officials nor being in the financial markets have signaled a shift in that direction.

To be sure, the Fed is not blissfully unaware of the shifting data mix that has evolved. Indeed, Chair Powell and other officials have lauded the cooling inflation trend seen in recent price data. But they are also keenly aware of the tariffs put in place this year and are holding the line because they expect some tariff-induced bump in inflation. Simply put, despite protestations to the contrary, the Fed has become more forecast dependent, even as it realizes its crystal ball is shrouded in a cloud of uncertainty. For one, it is unclear what tariffs will look like in coming months, given the chaotic rollout seen so far. It also remains to be seen how much of the tariffs will be “eaten” by sellers who might prefer to sacrifice some profits rather than lose sales. Finally, the Fed is clearly vexed over whether the tariff-induced bump in prices would be a one-off event or stoke an upward tilt in the inflation trend.

More immediately, some might wonder if the headline-grabbing anxiety over inflation has any merit at all. After all, higher tariffs have been in effect for several months, revenues from the duties surged in April and May – much to the benefit of Treasury coffers – yet higher inflation is nowhere to be seen except for a few tariff-sensitive goods in the consumer price index. So far, the main sector that is adopting Alfred E. Neuman’s “what, me worry” attitude is the bond market, where inflation- sensitive yields have retreated this week until Friday’s reversal. Ordinarily, the bond market is more forecast dependent than data dependent – and often a reliable leading indicator of events – so this contrary trend bears watching.

No doubt, bond yields respond to myriad influences, including a term premium that fluctuates along with the uncertainty fueled by unpredictable tariff and fiscal policies as well as the changing risk appetite of investors influenced by the ebb and flow of geopolitical tensions. Indeed, yields rebounded on Friday as Israel’s strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities sent oil prices surging. But the recent decline was also nurtured by incoming inflation data, which, as noted, has steadily defied the tariff-linked anxiety over the past several months. The latest data for May adds an exclamation point to the trend, as the consumer and producer price reports came in weaker than expected, suggesting the disinflation trend so rudely interrupted late last year is firmly back on track.

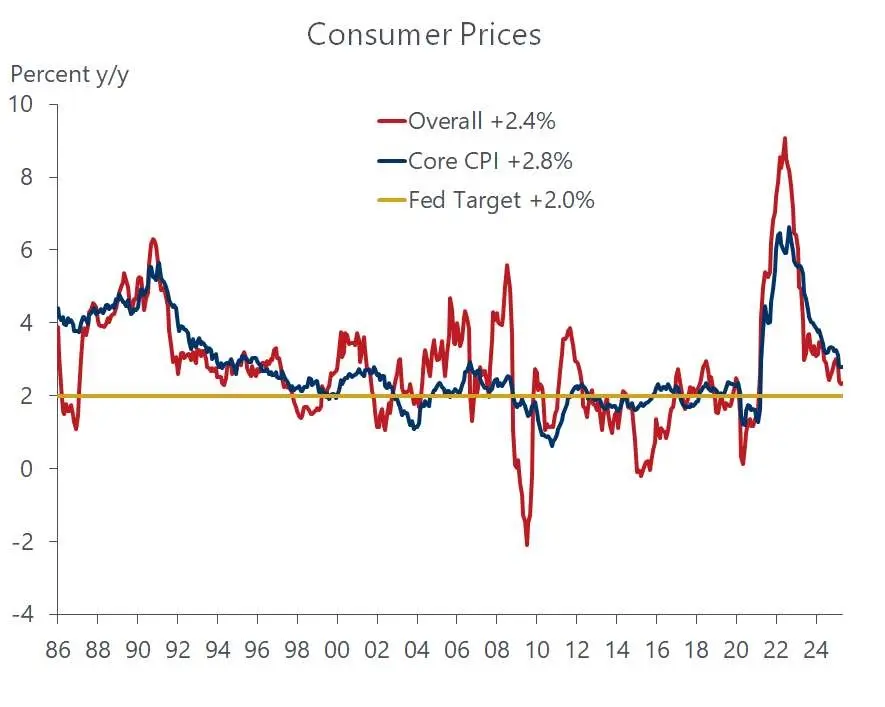

Both the overall consumer price index and the core CPI edged up by a slim 0.1 percent last month and the gains over the past year have cooled considerably over the past five months. The 12-month increase in the headline CPI slowed to 2.4 percent in May from 3.0 in January while the core inflation rate slid to 2.8 percent from 3.3 percent, where it had remained essentially unchanged over the previous eight months. While lower oil prices played a role in the slowdown, the disinflationary trend has encompassed a broad range of goods and services. Even housing costs, which have been slow to respond to a weakening housing market, broke lower in May. For the first time since late 2021, the year-over-year increase in shelter prices slid decisively below 4 percent, coming in at just under 3.9 percent.

Yet it would be a mistake to think the disinflationary trend will continue unabated, dodging the impact from tariffs. Granted, the pass through may be less than expected. Sellers recognize that consumers are more price sensitive than they were during the post-covid inflationary surge when households were flush with funds from generous transfer payments and muscular wage gains. The demand destruction from higher prices is now a greater threat, which is prodding businesses to absorb more of the tariffs than otherwise. But some high-profile retailers, including Walmart and Target, have already announced that they will pass on some of the tariffs to consumers and we expect a more visible inflation impact will be seen over the summer months.

Keep in mind that prices have been held in check so far because most of the goods sold are from inventories that were heavily stockpiled before tariffs were imposed. These pre-tariff prices will remain in effect until shelves are emptied and replenished with merchandise carrying the higher tariffs. That’s when we will get a better sense of whether tariffs have more of an impact on destroying demand or boosting inflation. If consumers rebel and zip up their wallets, the Federal Reserve is likely to ease policy sooner rather than later, particularly if weaker sales leads to a sharp increase in layoffs. Remember the Fed has consistently indicated that only a deteriorating job market would prompt it to cut rates earlier than planned.

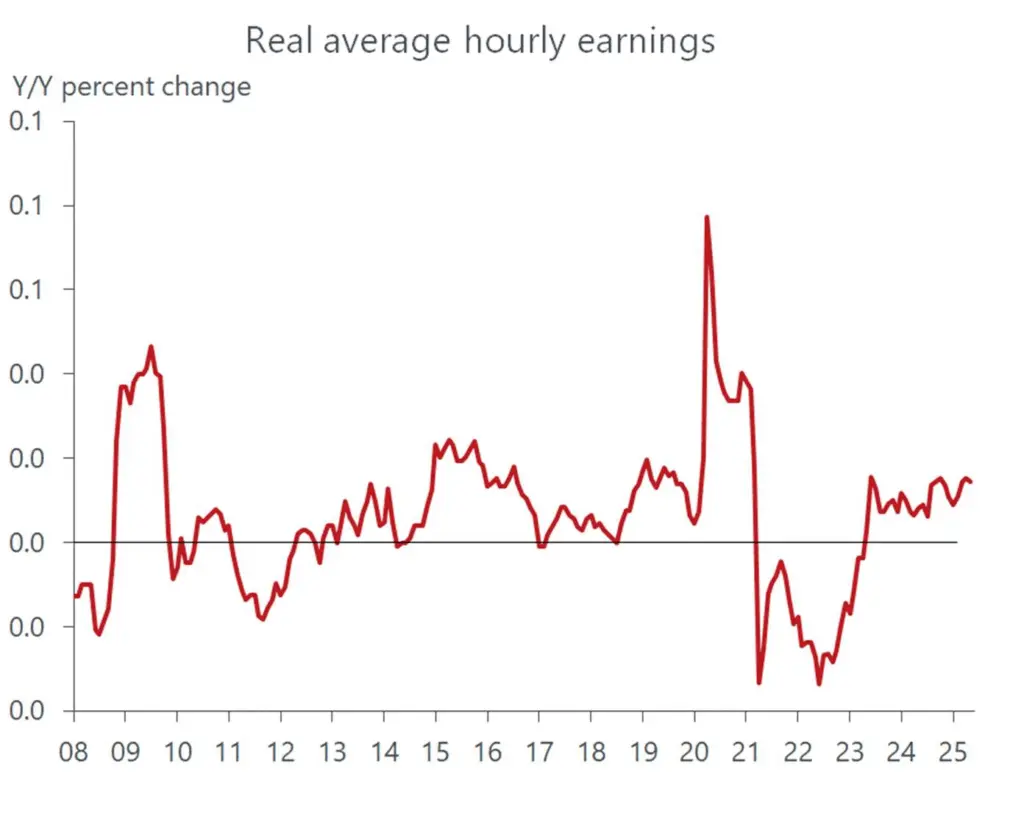

Conversely, if consumers accept higher prices and keep on spending the Fed will stay on the sidelines, keeping rates at their modestly restrictive levels to short-circuit a sustained inflation pickup. We expect the Fed to keep rates at current levels until late this year but recognize that the odds for an earlier move have increased, particularly if nascent signs of softer labor

conditions seen in the unemployment claims and other job-related data become more pronounced. That said, the cooling of inflation has bolstered household purchasing power by sustaining the solid gains in real wages. In May, real average hourly earnings exceeded the annual inflation rate by a healthy 1.5 percent. The bad news is that tariffs are expected to boost the inflation rate by around 1 percentage point even as wage growth will be slowing along with a softening job market. As that wage-price gap closes, sapping household purchasing power, the pressure on the Fed to start cutting rates will grow towards the latter months of the year.