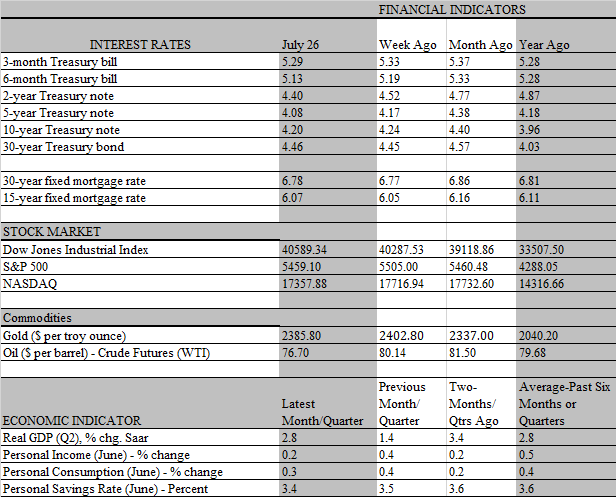

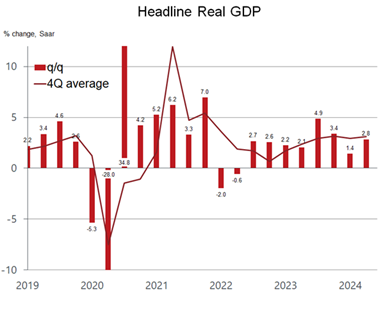

We always gave low odds that the Fed would cut rates at next week’s FOMC meeting, and the surprisingly vigorous GDP report for the second quarter only confirms that view. That said, the headline resilience revealed in the report obscures multiple storylines, some of which depict more vulnerability in the economy than suggested by the key growth drivers. Clearly, consumers are still in the driver’s seat, as their 2.3 percent spending increase contributed 1.6 percentage points to the 2.8 percent increase in GDP during the period. Their hefty contribution exceeded expectations, reinforcing a solid increase in equipment spending by businesses as part of their productivity-enhancing efforts.

While consumer spending came in stronger than expected, the overshoot did not come out of thin air. Households drew on some sturdy underpinnings, including a healthy job market, rising real wages and, importantly, solid balance sheets, buoyed by another quarter of strong gains in the stock market. The wealth effect gave a fillip to spending, as households save less when their assets appreciate and provide a greater sense of financial security in their golden years. Unsurprisingly, consumers drew down savings to finance their purchases, as the personal savings rate fell from 3.8 percent to 3.5 percent during the quarter (and further down to 3.4 percent in June).

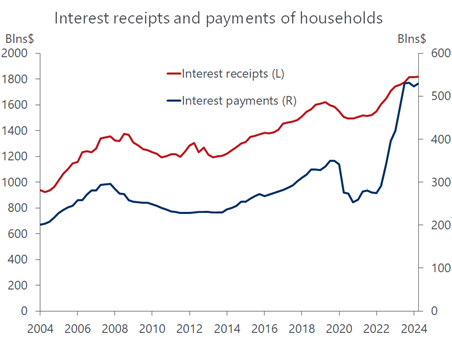

To the extent that wealth gains contributed to the strength in spending, it also highlights a bifurcated pattern of performance that is driving the economy. Upper income households account for the lion’s share of consumption, and they hold most financial assets. Not only are they the biggest beneficiaries of the outsized stock appreciation this year, but they also retain a large bond portfolio, which, thanks to the highest interest rates in two decades, also generated an ever-larger infusion of interest income. Most revenue from financial assets are saved rather than spent. But again, when households feel wealthier, they have less of an incentive to save and hence are more willing to spend a larger fraction of disposable income.

However, while upper income households are savers, the lower and middle-income cohort tends to spend every penny of their paychecks and, then some. That’s particularly the case when high inflation squeezes budgets and forces them to borrow to sustain living standards. A deeper dive into the GDP report reveals how differently the steep rise in interest rates since the spring of 2022 has impacted borrowers and savers. As expected, higher interest rates translated into higher income receipts from financial assets, providing savers with 17.2 percent additional interest income since early 2022. But that wealth gain is more than overwhelmed by the hit to borrowers, who saw their interest payments on nonmortgage debt soar by 92.6 percent over the same period.

To be sure, the surge in interest payments has not made much of a dent on aggregate consumer spending, thanks to the robust job market that has sustained a solid rise in paychecks for workers, including low-wage earners. But the strains from spiking debt-serving charges are clearly becoming more visible, as households are increasingly falling behind in their payments. Delinquency rates on credit cards hit the highest level since 2011 in the first quarter, according to the latest Federal Reserve data, and likely rose further in the second. With job and wage growth slowing, even as interest payments continue to rise, the increased debt burden of lower-income households heightens the downside risk to spending. The drag would come not only from the demand side, as consumers pull back, but from the supply side as well as banks tighten lending standards to protect balance sheets.

This prospect is another reason for the Fed to lower interest rates, despite the economy’s surprisingly strong performance in the second quarter. Keep in mind that the second quarter is in the rear-view mirror and it’s highly likely that the peak growth for the cycle is behind us. That said, the economy is not about to fall off a cliff, as suggested by the widespread jitters that appeared earlier when signs pointed to an abrupt consumer pullback. That concern faded with the release of a sturdy retail sales report last week and confirmed with the GDP and monthly personal income and spending reports this week. The latter, released on Friday, showed that consumer spending lost little momentum at the end of the period, rising by a respectable inflation-adjusted 0.2 percent in June. We note, however, that the spending increase outpaced the slim 0.1 percent increase in real disposable income, and the savings rate slipped to 3.4 percent during the month, the lowest since December 2022.

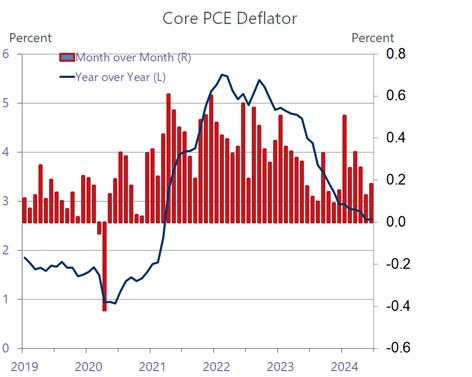

As noted, the Fed is unlikely to pull the rate-cutting trigger at its upcoming meeting next week, as the economy continues to hold up well and policy makers are still waiting for more evidence that inflation is moving more convincingly towards the 2 percent target. The good news is that progress on the inflation front continued in June, as the Personal Consumption Deflators -the Fed’s preferred inflation measures- eased further. The overall PCE ticked up by 0.1 percent from May and the increase over the past year slowed to 2.5 percent from 2.6 percent. The more relevant core PCE, which removes volatile food and energy prices, proved stickier, rising 0.2 percent from May and the same 2.6 percent over the past year as the previous month.

However, the slow grinding down in the year-over-year rate is well telegraphed and should not deter the Fed from cutting rates, as upcoming data will be compared with the sharply retreating inflation readings over the last six months of 2023. Hence, the Fed will pay more attention to the sequential monthly changes, and if they remain in the 0.1-02 percent range for a sustained period, that should suffice to prompt the Fed to move, even if the year-over-year increase stalls out at 2.5 percent by the end of the year. So far, so good. Over the past three month, the overall PCE increased at an annual rate of 1.5 percent and the Core PCE by 2.3 percent.

Importantly, the inflation retreat is moving faster than the slowdown in wage growth, allowing real earnings to stay on a positive trajectory. The sustained increase in purchasing power is cushioning the drag from high interest rates, but as job growth slows in coming months, so too will wage growth. We suspect that the Fed will send a strong signal at next week’s policy meeting that the time for proactive rate cuts to short-circuit an abrupt weakening in the job market is drawing closer. The financial markets are firmly priced for a September move, which aligns with our forecast; we doubt the Fed would want to upset investor expectations and risk a severe correction. The wealth effect works both ways and a negative shock would amplify the spending drag that is now confined to financially-strapped lower income households.