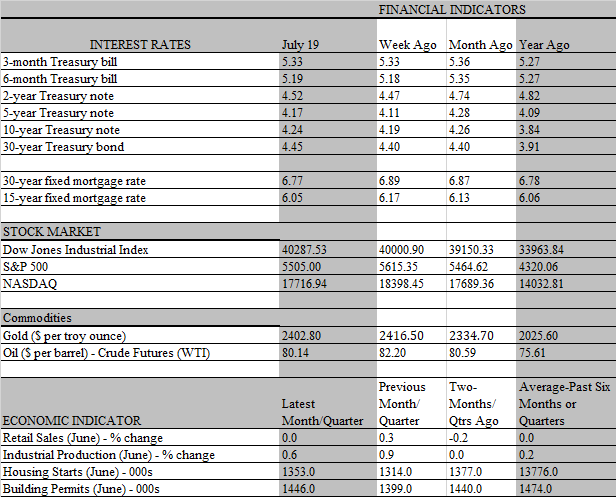

The debate over when the Federal Reserve should start cutting rates is continuing apace, with no clear resolution in sight over the near future. Unfortunately, incoming data is not providing much clarity. The case against cutting sooner rather than later is that the economy is doing just fine, thank you, under the current high-rate regime. According to the Atlanta Federal Reserve’s latest GDPNow monitoring tool, the economy is tracking a 2.7 percent growth rate in the second quarter, a healthy pace by historical standards, and well above the 1.4 percent increase in GDP posted in the first quarter. With inflation still comfortably above the Fed’s 2 percent target and businesses still hiring at a sturdy pace, what’s the rush?

The case for cutting rates sooner rather than later is just as compelling. While the headline growth rate appears healthy, cracks in the economy are becoming increasingly evident; what’s more they will continue to deepen as the lagged effects of the highest interest rates in more than two decades take an ever-increasing toll on the economy. The housing market is already a mess, lower income households are having trouble meeting debt payments, as delinquency rates on credit cards and auto loans are rising. And while the job market is still pumping out a healthy number of payrolls each month, the gains are coming from a narrowing group of sectors; the government and health care accounted for fully three-quarters of the 206 thousand payroll increase in June. Importantly, the unemployment rate continued to tick higher for the third consecutive month, and the half percent increase from its 3.6 percent low a year ago to the current 4.1 percent is already steeper than is usually seen outside of a recession.

Since it takes at least several months for monetary policy to effect broad changes in the economy, the argument that the Fed should move now to prevent the economy from descending into a recession has much support. However, the Fed is highly data dependent and it, understandably, is waiting for more convincing data that its past actions have put inflation on a sustainable course towards its 2 percent target, while keeping its fingers crossed that the economy doesn’t crash beforehand. To its credit, the Fed is feeling more confident that inflation is moving in the right direction and less confident that the economy can withstand high rates for much longer. Hence, the bet on Wall Street, is that a rate cut is likely to occur in the fall, a prospect that is supported by recent comments of several Fed officials. Some commentators believe that to avoid the appearance of influencing the election, the Fed should move even earlier, pointing to the upcoming policy meeting on July 30-31.

We doubt a move late this month is in the cards, but it is highly likely that policymakers will send the strongest signal yet that a September launch date is on the radar at the meeting. One reason an immediate cut is not warranted is that incoming data continue to portray more strength than weakness in the economy. That’s starkly evident by this week’s key economic report, which portrays a consumer that is still showing a considerably amount of vigor. Since consumers account for more than two-thirds of total economic activity, the risk of a recession is slim as long as they keep their wallets open. If the retail sales report for June is any indication, households are far from going into hibernation.

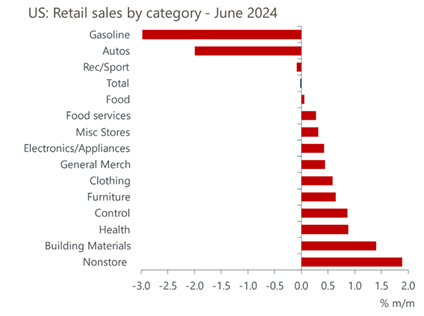

To be sure, the headline reading does not seem overly vigorous. Total retail sales were unchanged last month, hardly a ringing endorsement of strength. But as usual, the devil is in the details and a deeper dive into the report does portray more strength than weakness. Most notably, a price-related decline in gas station sales and a fall back in auto sales, which was due to a widespread cyberattack on dealerships, were entirely responsible for the headline weakness. Spending in almost every other category rose strongly during the month, and there were significant upward revisions to the previous months as well. Both of those downward influences were well telegraphed in advance. Gas prices fell around 14 cents a gallon between May and June, which weighed heavily on the dollar value of gas station sales. Meanwhile, the already released industry reports of lower auto sales foreshadowed the dollar drop in the retail sales report.

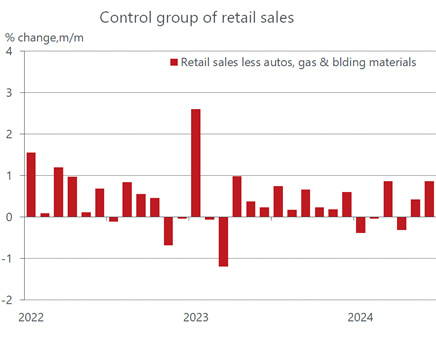

But if those two categories are removed from the total, things look much more robust. Sales excluding gas and autos staged a sturdy 0.8 percent increase, the strongest since January 2023. Go even deeper to strip out building materials, and the monthly gain rises to 0.9 percent. That stripped-down version is important because it represents the so-called control group of sales, which enters directly into the Commerce Department’s calculation of personal spending on goods in the GDP accounts. Significantly, the biggest driver of the control group of sales came from nonstore vendors, a.k.a. Internet shopping, where sales surged by almost 2 percent. This is a volatile category and ordinarily a big monthly gain is followed by a setback the following month. However, that’s not likely to happen this time, as the just-completed Amazon Prime Day sale is likely to give non-store sales another sizeable fillip in July.

The sizeable increase in the control group of sales together with the upward revisions to previous months indicate that consumers provided a decent amount of heft to the second quarter’s growth rate. However, it is important not to overstate the importance of the retail sales report on the strength of consumer spending. One reason the strong numbers are somewhat of a surprise is that many thought goods purchases, which are the bulk of retail sales, would have faded considerably in the postpandemic period, since households are no longer confined to their homes for health reasons. But the prevalence of remote work has changed that dynamic, resulting in much stronger goods purchases than expected, which we believe will stick in the decades ahead.

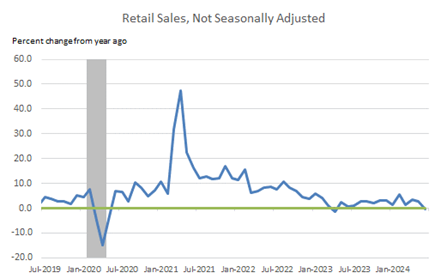

But the change in work habits is also a reason to question the accuracy of the retail data because adjusting for seasonal influences has become harder. Indeed, a wide gap between the raw, unadjusted, and the seasonally adjusted data has opened up. On a non-seasonally adjusted basis, for example, retail sales fell 5 percent in June and are virtually unchanged from a year ago. This departs sharply from the seasonally adjusted data, which show no change in sales from the previous month and a 2.3 percent increase over the past year. Simply put, goods purchases may not be a strong as the retail sales report indicates. Indeed, ongoing announcements from large retail chains that they are cutting prices to lure back customers strongly suggests that consumers have become much more price sensitive and less flush with funds than they were a year ago. Retailers are also looking for ways to curb labor costs, including the wider use of robots in fast-food chains, reflecting a broader stepped-up drive to employ labor-saving technology in their cost-cutting efforts.

From our lens, the economy is in a good place, running neither too hot nor too cold. But the catalysts that have driven inflation sharply higher and prompted the Fed to drive interest rates up to the highest levels in more than two decades have faded and the need to keep rates at the current elevated levels is no longer justified. Inflation may be retreating too slowly for the Fed, but it is on a steady slowing trend that should continue as the labor market has reached a better balance between the demand for and supply of workers. Meanwhile, the toll that high rates is taking on lower income households will soon spread to the broader population as a softer job market and slowing wages will erode consumer purchasing power. The economy is holding up as we head into the second half of the year, but some rate relief will be needed by the fall if 2024 is to escape a recession.