Once again, the U.S. economy is showing that it is not ready to roll over in the face of higher tariffs and other distractions that many thought would be taking a more damaging toll by now. Nor does it seem to be in the grips of a tariff-induced inflationary spiral about which the headlines have been sending warning signals for several months. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that after a few jittery months, the financial markets are taking things in stride. Stock prices continue to race ahead, reflecting not only the stable macro environment, but also decent earnings reports that are coming in. Likewise, the ebb and flow of expectations regarding when the Fed might cut interest rates continue to stoke some volatility in the bond market. But the gyrations have become tamer and overall, market yields are little changed from where they stood at the start of the year.

The resilience exhibited by both the economy and the financial markets has created a new risk that is currently making the rounds. Simply put, an aura of complacency has permeated the mindset of traders and investors, making them highly vulnerable to unexpected developments. It is impossible to forecast where, or when, such developments would take place. The most obvious starting point would, of course, be tariffs, which have been the most attention-getting event since the start of the year. Yet incoming reports have time and again suggested that all the nefarious threats to the economy have turned out to be more bark than bite. Understandably, the markets have become somewhat inured to the “crying wolf” sounds and are looking the other way.

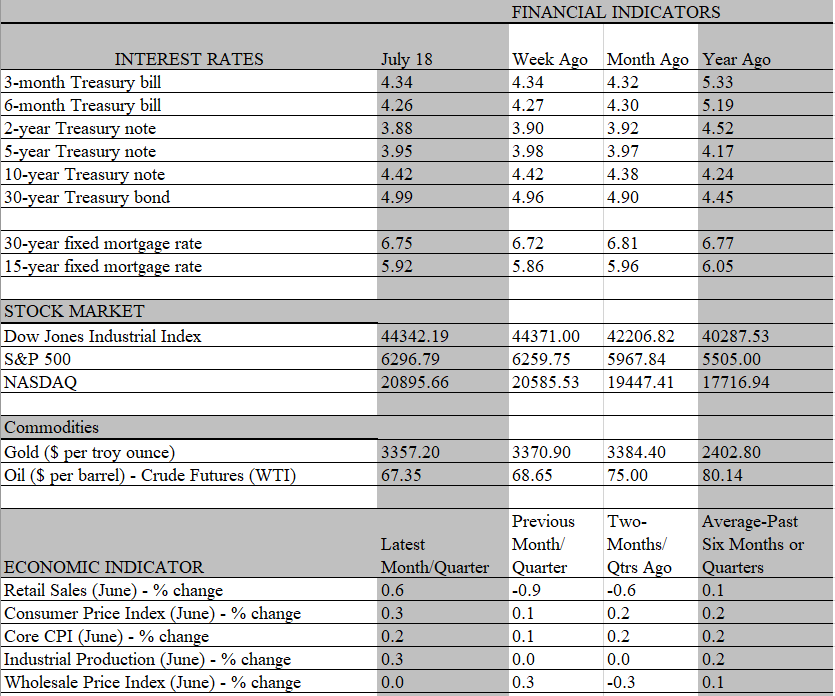

While we don’t think that we are staring at the calm before the storm, we do caution that it is still early days in the tariff drama, and signs of trouble ahead are popping up. Granted, the headline reports released this week support that “what me worry” mindset. The retail sales data for June, for example, suggest that consumers are keeping their wallets open, and their shopping behavior is the engine that drives economic growth. Overall, retail sales rose by a stronger than expected 0.6 percent last month, rebounding nicely from declines in each of the two previous months. Nor was the gain powered by one or two sectors, as consumer spread their outlays over a broad swath of retailers. Indeed, of the 13 major retail categories, only two – furniture and electronics – showed a slip in sales, and those setbacks were a barely visible 0.1 percent.

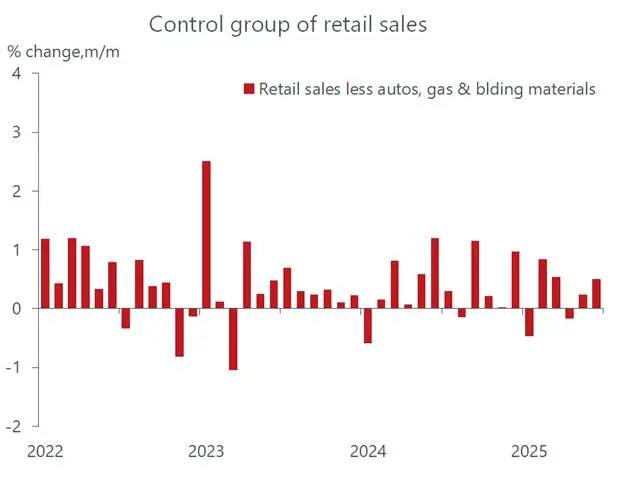

Sales at service stations were unchanged, but everything else was up, paced by a 1.2 percent increase in auto sales. As noted, consumers are the main engine of growth, but not all the retail categories are included in the important personal consumption calculation that accounts for about 70 percent of GDP. However, it is possible to carve out the sectors in the retail sales report that do enter that calculation. This so-called control group of sales – the total excluding food, autos, building materials and gasoline – also staged a nice gain, rising by 0.5 percent last month, although the shine of that increase is dimmed by a downward revision of the previous month’s increase.

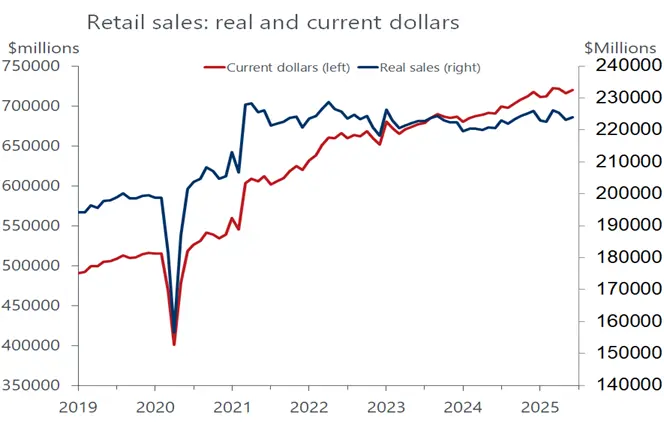

On the surface, therefore, there is nothing to complain about. Unless, that is, you get the feeling you are paying more for things and getting less. If you do, you’re in good company because the physical goods you are getting in return for your dollars are not growing. In other words, the dollars spent are being gobbled up by higher prices. Keep in mind that the retail sales data are expressed in nominal or current dollars. When adjusted for inflation, consumers are getting far less bang for the buck. In fact, real or inflation-adjusted, sales have barely budged since the start of the year, and in recent months have actually declined. And while it’s hard to prove that the higher prices reflect the tariffs put in place since early April, it is no coincidence that spending on furniture and electronics were the only two categories to fall last month, as these products are on the front lines of tariff-related price increases.

So, if tariffs are likely showing up in the retail sales numbers, why aren’t they showing up in the inflation measures. That’s a legitimate question, particularly in the wake of the latest consumer price reports, which continued to come in on the tame side last month. The overall consumer price index rose 0.3 percent in June, a bump up from the 0.2 percent in May but very much in line with expectations. The core CPI, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, also remained subdued, increasing by 0.2 percent. Compared to a year earlier, both measures increased faster than the previous month, but both remained below the 3 percent annual inflation rate that prevailed in January.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that inflation is not falling, which the Fed would like to see moving steadily towards its 2 percent target. That hasn’t happened, and with the job market holding up, it remains a long shot that the central bank will cut rates at its upcoming meeting later this month, despite the withering criticism from President Trump. If anything, the president’s attacks on the Fed may be having just the opposite effect, as a rate cut would give the impression that the Fed is caving in to political pressure. Such an event would almost certainly spark turmoil in the financial markets and send longer-term interest rates upward, reflecting heightened inflation expectations.

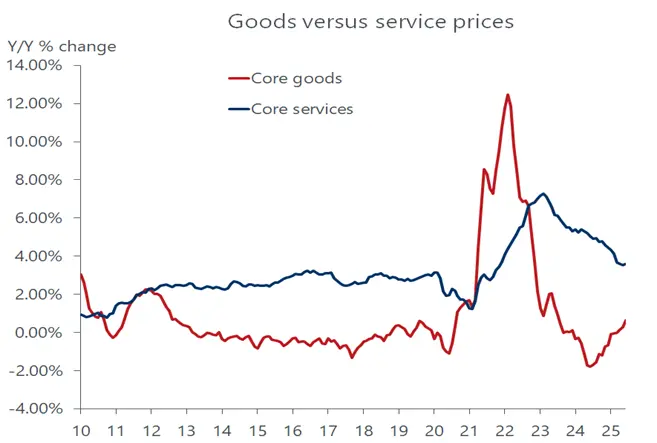

Importantly, while the much-anticipated boost to inflation from tariffs has yet to fully materialize, it is seeping through. Keep in mind that the consumer price index covers a basket of goods and services, but most dollars spent by households are for services. So far, service prices are behaving well and putting a lid on overall inflation. But the goods side, not so much. Here is where tariffs have their main impact, and this part of the inflation ledger is beginning to show the tariff impact. What we are seeing is the mirror image of the great inflation moderation that took place over the last half of 2024, when stressed out Covid supply chains came unglued and goods poured back to the market, driving goods inflation sharply lower.

The supply chain is still operating smoothly, as there is no longer a shortage of products. But those products, many of which are brought in from overseas, now have higher tariffs. For a variety of reasons, the tariffs are not being fully pass through to consumers. Businesses usually carry two to three months of inventories, and many of the goods being sold are from stocks acquired before tariffs took effect. But some passthrough is taking place and goods prices are no longer deflating as they were last year. For the first time in April, goods inflation turned positive and has been increasing since.

The big question for the Fed is whether the price boost from tariffs will be a one-time event or drive the inflation trend higher, something that would push back the rate-cutting campaign. From our lens, if all the threatened tariffs that Trump plans to put into effect on August 1 is realized, the price bump would be significant but so too would the hit to household budgets, leading to much weaker consumer spending later this year. That, in turn, should eviscerate the pricing power of sellers and keep inflation in check even as it becomes a big drag on demand. Hence, by later this year, the stage will be set for the Fed to worry less about inflation and more about a deteriorating economy that could drift into a recession. The pivot to cutting rates should begin later in the year and continue throughout 2026.