This weeks calendar was packed with economic news, headlined by the Federal Reserves first policy meeting of 2025. As expected, the Fed kept its finger on the pause button, putting the fourth rate cut of the easing cycle on hold until inflation shows more tangible signs of cooling. With the economy holding up well and consumers still spending freely, officials see little downside risk to the economy or job market of keeping rates at current levels. The summary statement of policy intentions issued after the meeting contained a few sentences that sounded mildly more hawkish than the previous statement; but Chair Powell brushed that off at the post-meeting press conference as merely an attempt to tighten up the language. However, Powell acknowledged that rates are still restrictive, suggesting that the Fed retains a bias to cut rates at some point, although the timing remains uncertain.

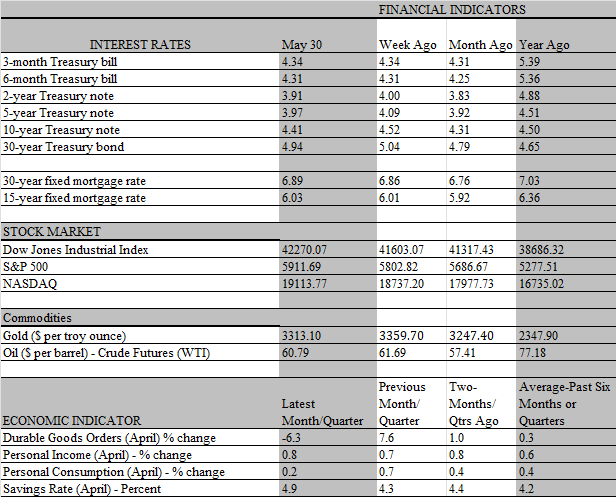

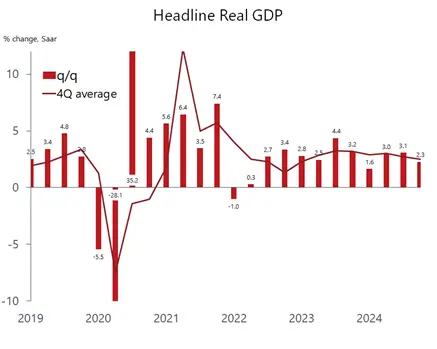

The Fed meeting took place a day before the fourth-quarter GDP report came out, which, while preliminary, closes the books on the economy’s performance in 2024. On the surface, it appears that activity lost some momentum towards the end of the year, as GDP slowed to a 2.3 percent growth rate from 3.1 percent the third quarter. But the headline reading understates the economys strength. A look under the hood shows that slower inventory restocking was the biggest drag on growth during the period, slicing nearly 1 percentage point from the growth rate. Simply put, businesses could not keep up with the muscular increase in demand, as personal spending surged by a 4.3 percent annual rate, the strongest since the first quarter of 2023, paced by a torrid 12.1 percent increase in durable goods purchases. Final sales of domestic product, which excludes the inventory drag, increased by 3.2 percent, which is almost spot-on with the 3.3 percent increase in the previous quarter.

To be sure, the spike in consumer spending in the fourth quarter is unsustainable. Replacement demand for vehicles destroyed by recent hurricanes contributed to the strength, and there are signs that consumers pulled forward some purchases to beat higher prices linked to President Trumps tariff threats. Recent surveys reveal that household inflation expectations have increased, which may provide cover for businesses to raise prices if, and when, tariffs are put into effect. As of this writing, 25 percent tariffs on Mexico and Canada and 10 percent additional tariffs on imports from China are set for February 1. So far, Trump has given no signal that he is backing off on the tariff threat, which is designed to force trading partners to comply with non-economic demands, i.e. on immigration and drug inflows.

But while temporary influences may have boosted demand in the final months of 2024, the expected setback should not be dramatic. Households are still in good financial shape and a healthy job market that is generating solid income gains should keep consumers in a spending mood. True, most of the savings accumulated during the pandemic era have been exhausted, and households are spending a bigger fraction of incomes to sustain living standards. The personal savings rate slipped to 3.8 percent in December, according to Fridays personal income and spending report, the first reading below 4 percent in two years. But that slippage is offset by the ongoing appreciation of portfolio assets that is adding wealth to the balance sheets of upper-income households, who account for the biggest share of spending in the U.S. Stock prices started the year on a firm footing, notching a gain of more than 3 percent in January.

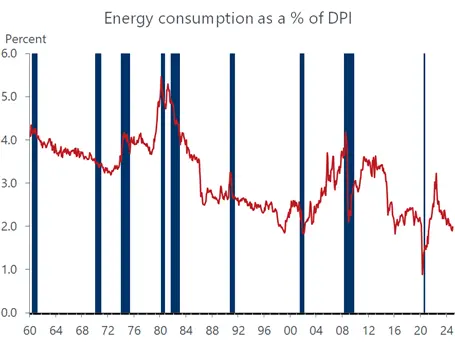

And although households spent more than they earned in December, they still enjoyed a solid 0.4 percent increase in personal incomes during the month, leaving it 5.3 percent higher than a year ago, which comfortably exceeds inflation. Even after subtracting taxes and inflation, disposable income moved up for the fourth consecutive month, albeit by a slim 0.1 percent. Interestingly, President Trumps strident attack on oil prices, which he claims is a major source of inflation and high interest rates, is not causing much of a strain on the collective budgets of households. As a share of disposable income, energy consumption has rarely been lower than it is now. What’s more, crude oil prices are declining again, falling more than 10 percent over the past two weeks.

That said, sticky inflation remains a thorn in the side of the Fed, and price hikes stemming from higher tariffs is bound to cause some pushback from consumers. If so, it would put policymakers into even more of a bind, as they would have to weigh the downside growth risk from higher tariffs against the upside inflation risk from the tariffs. Chair Powell noted the complexity of the tariff issue at his press conference, and understandably stayed away from predicting what the consequences would be. Instead, the Fed is relying on incoming data to guide its decisions, and the latest reports although backward looking do support the decision to keep rates unchanged for now.

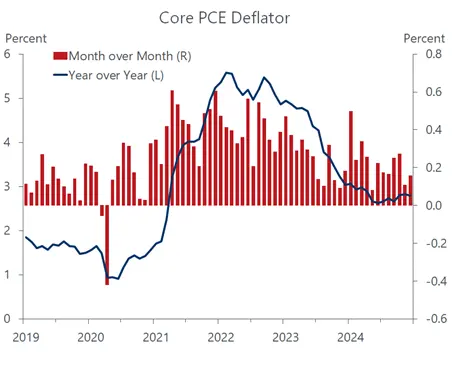

As noted, the major cylinders powering the growth engine consumers and the job market are chugging along, driving the economy at or slightly above its speed limit heading into the new year. Meanwhile, inflation has stubbornly refused to downshift, as the core personal consumption deflator the Feds preferred inflation gauge increased 2.8 percent in December from a year ago for the third consecutive month. Nor are some key components behind the inflation gauge helping matters. Housing costs ticked up in December as did the supercore group (services excluding energy and housing costs) that the Fed closely monitors. The bumpy road towards the Feds 2 percent inflation target is littered with more potholes than expected, prompting the Fed to slow the ride.

The good news is that the influence of labor costs on inflation continues to wane. Like its preferred inflation gauge, the Fed also has a favorite measure of labor costs, the Employment Cost Index. The overall ECI came in a touch stronger in the fourth quarter, rising by the same 0.9 percent as the third quarter, with the bigger lift coming from government workers whose wages are still catching up to the private sector. However, total compensation growth in the private sector continues to grind steadily lower, notching the smallest year-over-year increase since the second quarter of 2021. That has to give the Fed comfort and keeps the door open for rate cuts when the disinflationary trend resumes, which we expect over the coming months. The timing of the next cut is uncertain, but if the tariff impact on inflation is negligible either because it is quickly removed or remains as a bargaining chip we believe a cut as early as March is still on the table, particularly if the labor market softens meaningfully.