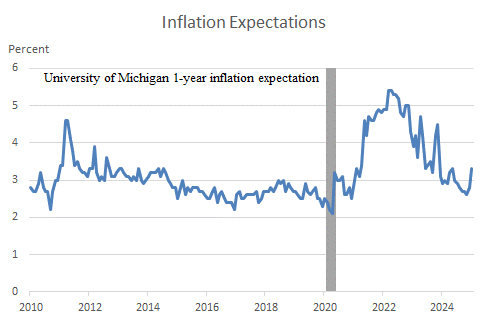

This week was a quiet time for economic data, but the floodgates will open next week with a slew of key reports on consumer spending and inflation for December as well as the governments first tally on how the overall economy performed in the fourth quarter through the lens of the GDP report. Importantly, the Federal Reserve will have its first policy meeting of 2025; unlike the three previous meetings beginning with September, which included rate cuts each time, the central bank is expected to stay on the sidelines at this confab. Just how long a pause will be in effect is still uncertain; but triggers for the next cut is likely to come sometime in the spring or early summer as the inflation retreat, which stalled out over the second half of last year, should resume.

The other trigger, of course, would depend on upcoming job reports, notably more visible signs that the labor market is softening. So far, the evidence is lacking, at least according to the headline measures of payroll growth and unemployment. Decembers jobs report, which featured a blockbuster increase in payrolls, put the kibosh on further policy easing this month. That, plus the still-muscular spending habits of households, as portrayed in the strong retail sales report for December, provided the Fed with further evidence that the economy can survive quite nicely without the help of another rate cut at this time. Even the rate-sensitive housing market seems to be surviving 7 percent mortgage rates, which seemed unfathomable a year ago.

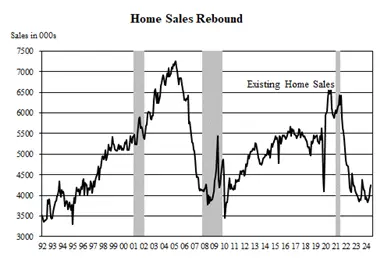

To be sure, 2024 was a dismal year for home sales, as previously owned homes which account for the bulk of transactions suffered through the worst sales market since 1995. But the shock and awe of surging mortgage rates that sent sales on a downward spiral in 2023 and the first half of 2024 may be wearing off. Home sales rose in each of the last three months of the year, punctuated by a 2.2 percent rise in December, which lifted sales for the month a hefty 9.3 percent above the year-earlier level. That too was the third consecutive month of year-over-year growth, following three years in which sales fell in every month from the previous year. Clearly, affordability is still a major challenge for many home buyers, but more households are accepting the fact that the era of low rates with mortgages yielding 3-4 percent are over. What’s more, three years of solid job and wage growth have enabled incomes to gradually grow into the high cost of purchasing a home.

That said, with mortgage rates still hovering near the highest levels in more than two decades, it would be a mistake to expect home sales to take off. At best, buyers will continue to process high rates and continue to gradually enter the market as long as incomes continue to increase and job creation remains strong. That, of course, is where the rubber meets the road. As noted, job growth ended last year on a blockbuster note, but for 2024 as a whole, employment growth slowed for the third consecutive year. We expect that slowing trend to continue even as economic growth is sustained close to last years pace. One reason: productivity is getting a boost from technology as well as more intense company efforts to contain labor costs. In short, fewer workers will be churning out more product, keeping GDP growth on a solid upward trajectory.

Critically, the slowing growth in payrolls will not necessarily lift the unemployment rate much above the roundly 4 percent level. That’s because reduced immigration combined with large-scale deportations proposed by President Trump, will sharply retrain growth in the labor force. Hence, fewer jobs will need to be created to accommodate a smaller increase in the labor supply. The so-called breakeven rate to keep the unemployment rate steady is likely to be closer 100-150 thousand than the roundly 200 thousand needed in recent years to absorb the influx of migrants as well as growth in the domestic population. The bad news is that some sectors, such as health care, construction and agriculture that rely heavily on immigrants for workers will be facing labor shortages, which is likely to put upward pressure on prices for the goods and services they provide.

As it is, a look under the hood of an otherwise strong job market reveals emerging cracks that foreshadow the softer labor conditions we expect to unfold as the year progresses. True the historically low unemployment rate seen now is a testament to the still relatively tight job market. But the low jobless rate is more a reflection of employers holding on to their workers rather than strong demand for new workers. Indeed, the hiring rate measure under the Labor Departments Jobs Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (commonly referred to as the JOLTS report) has fallen to the lowest level since 2010 in November. That means workers who are unemployed and looking for a job are finding it harder to land a position.

That seemingly contradiction between a low unemployment rate and high job finding difficulty is captured in the trend in applications for unemployment benefits. New claims remain at historically low levels, which confirms that companies are not laying off workers. But the number of unemployed workers receiving jobless benefits has been steadily rising, reaching the highest level in more than three years in the week ending January 11. Not surprisingly, the length of time job seekers have been out of work has also been rising. Another measure of this trend can be found in the so-called job-finding rate, which tracks the share of unemployed workers in any month that lands a job the next month. This gauge has been trending down; the average rate over the last three months through December is hovering near the lowest since the summer of 2021, when the economy was just emerging from the deep pandemic-induced recession.

Still, fully 96 percent of people in the labor force have jobs and their paychecks are driving the consumer spending cylinder that keeps the economy’s growth engine chugging along. As noted, we do not expect that share to decline significantly this year, but the low unemployment rate is not the best measure of labor market strength. Nor does it signify how people feel about job conditions. Although most have jobs, just about everyone knows someone who is looking for work and the increased difficulty they are having in landing a position. This affects the mindset of workers, causing heightened concerns over job security. The sharp decline recently in the share of workers quitting voluntarily is a time-honored sign of lowered confidence in the job market. Over time, this impacts spending habits.

Indeed, the University of Michigan Sentiment survey released on Friday may contain an early indicator that rising job insecurity is taking hold, as the survey revealed that nearly 50 percent of households expect unemployment to rise this year, the highest since the pandemic recession. On the surface, this would suggest households plan to rein in spending and build up a rainy-day savings cushion. However, the survey also revealed just the opposite, that households plan to step up purchases in the near term to beat the price hikes many believe will follow Trumps proposed tariffs. If they follow through, that would give a bump to growth in the first quarter, putting Fed rate cuts on hold even longer. These crosscurrents are what makes the job of policy makers so challenging, and they are not about to fade anytime soon. While no rate change is expected at next weeks policy meeting, the markets will be laser focused on Chair Powell’s subsequent press conference for insights into how Fed officials are balancing these crosscurrents in their thinking about future rate-setting decisions.