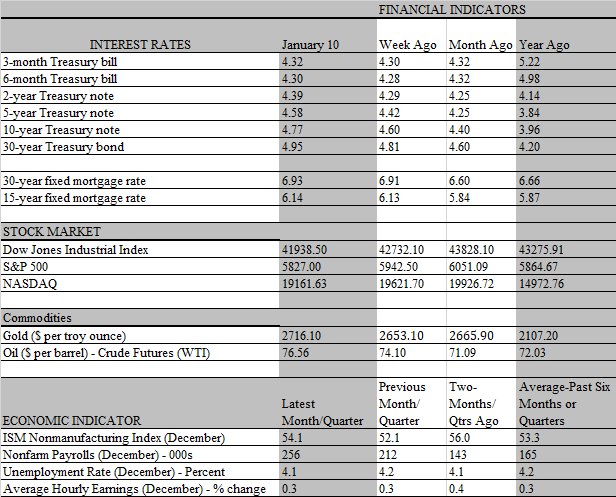

Its been a rough ride in the financial markets over the past month. The S&P 500 has fallen by more than 4 percent since hitting a nearby peak on December 6, while the bellwether 10-year Treasury yield has spiked by nearly three-quarters of a percent, hitting a 15-month high of 4.80 this week. Perceptions as much as fundamentals have underscored the bearish turn of events. Until Fridays stronger than expected jobs report, there were no major surprises on the economic front. As advertised, policy uncertainty linked to the incoming administration is wreaking havoc on investor expectations, stoking the volatility that many anticipated following the election. Its still unclear how much of the headline-grabbing campaign proposals will see the light of day and how they would ultimately impact the economy. About the only outcome around which a consensus has formed is that the prospect of higher tariffs, lower taxes and increased deportations heightens the risk that inflation will be stickier than otherwise over the foreseeable future.

That is also the takeaway from the minutes of the Feds last policy meeting in mid-December released this week. Most officials endorsed the quarter point rate cut taken at the meeting, but several expressed concern over the inflationary consequences that Trumps trade and immigration policies might entail. The minutes confirms what was implied in the SEP released following the meeting. The median forecast for growth and unemployment in 2025 barely changed from the previous projections revealed last September, but the inflation rate was kicked up from 2.1 percent to 2.5 percent in 2025. With the main inflation drivers growth and employment mostly unchanged from the previous forecast, some officials at least subjectively incorporated the heightened inflation risk from tariffs and deportations into their thinking.

The more hawkish stance of the Fed clearly had a big influence on market perceptions, as the expectation of fewer rate cuts this year than thought three months ago sent both stocks and bonds reeling. Those expectations were cemented following Fridays jobs report, which featured a much bigger payroll increase in December than expected 256 thousand versus a consensus estimate of 160 thousand. Following the report, interest rates across the board increased and traders immediately pushed back the likely timing of the Feds first rate cut by several months. The markets are still pricing in two rate cuts this year, which is the updated Feds forecast as well, but the timing has understandably been pushed back.

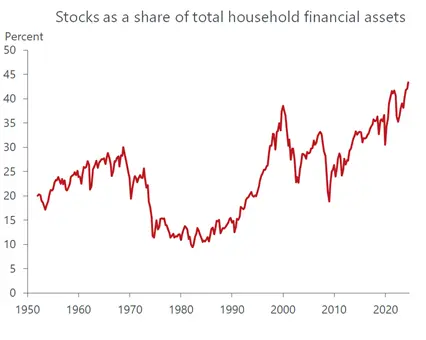

The pullback in stock prices on Friday brings the cumulative loss since December 6 to more than 4 percent. That’s still far from correction territory. However, any deepening of the wealth erosion from a slumping stock market could take a toll on consumer spending. Lower income households have already maxxed out on credit cards and their diminished borrowing capacity is prompting a spending pullback. This is not a deal breaker for the broader economy as long as middle- and upper-income households who do most of the heavy lifting on consumption keep their wallets open. Importantly, the enhanced spending capacity of this cohort derives in good part from healthy balance sheets that have been buoyed by surging asset values.

While increasing home values and housing equity — have contributed significantly to burgeoning net worth, appreciating stock portfolios have had a growing influence in recent years. Stock prices have increased more than 20 percent in each of the past two years, a back-to-back performance not seen since 1997-98. Unsurprisingly, stock holdings have become a more important asset for households, accounting for a record 43.4 percent of total financial asset holdings in the third quarter of last year compared to an average of 30.5 percent in 1997-98. Of course, this can be a double-edged sword as the positive wealth effect on consumption from strengthening stock portfolios can morph into a negative influence should a deep correction wipe out a big chunk of the gains.

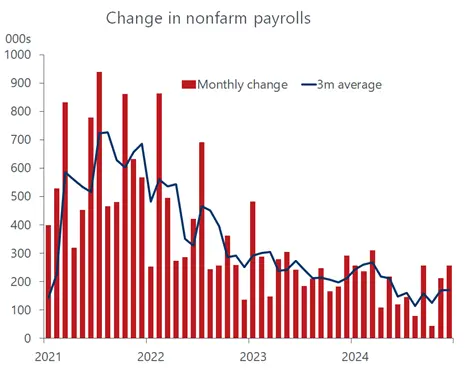

That said, the biggest influence on consumer spending the economy’s main growth driver is jobs, not the stock market. The stronger-than-expected increase in payrolls last month is a sure sign that labor conditions remain on a solid footing. Hence, fears of a softening job market that spurred the Fed to cut rates over the second half of last year have subsided. Along with the tick down in the unemployment rate from 4.2 percent to 4.1 percent, Fed officials are more confident the economy can withstand the current level of rates for a while longer. Hence, they are likely to pause the rate-cutting cycle until more signs of weakness come into focus and, importantly, the stalled disinflationary process resumes.

One encouraging note in the jobs report is that it confirms the Feds view that the labor market is not a source of inflationary pressures. Despite the strength in payrolls, workers earnings remain well contained, as average hourly earnings rose 0.3 percent in December and 3.9 percent from a year ago. Hence, for the ninth consecutive month earnings growth has remained at 4 percent or less, a threshold that is consistent with the Feds 2 percent inflation target given the recent trend in productivity. We caution, however, not to read too much into the restraint in average hourly earnings, as that metric is heavily influenced by the changing mix of job gains. In December, a larger than usual contribution to the increase in payrolls came from lower-paying jobs, most notably in retail, leisure and hospitality and the government.

Still, forward-looking indicators point to continued moderation in wage growth, including a softening in the quits and hiring rates. True, job openings staged a stronger increase in November than expected, but there is no guarantee that employers will fill those positions. Some believe the increase may reflect a bounce in company optimism following the election, as the prospect of deregulation and lower taxes raises growth expectations. Employers may not want to cope with the labor shortages they encountered during the post-pandemic recovery and decide to get ahead of the problem. The threat of massive deportations, which would surely detract from the labor supply, only amplifies that concern.

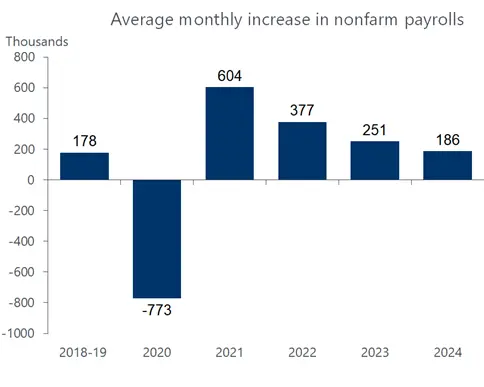

Likewise, the wild moves in the stock and bond markets on Friday may well be an overreaction to the jobs report. Even with the spike in payrolls, the overall trend in job growth continued to cool last year. For the year as a whole, the increase in nonfarm payrolls averaged 186 thousand a month, a marked cooling from 251 thousand in 2023 and only a tad above the 178 thousand monthly average during the two years prior to the pandemic. Over the last three months of 2024, payroll gains averaged 170 thousand a month, which is very close to a balanced labor market.