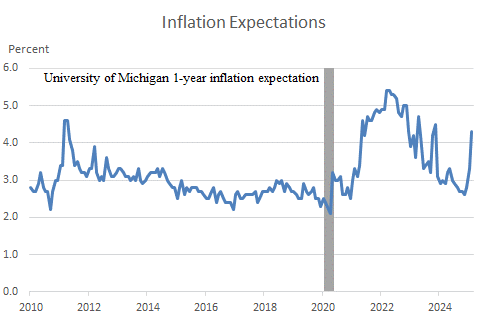

How you look at this Friday’s jobs report depends on whether you are a half-full or half-empty type of person. Those with a more jaundiced view of the world will view the slowdown in payroll growth in January as an ominous sign, the first inkling that labor conditions are poised to weaken significantly as the year progresses. The more upbeat observer, however, will look at the January slowdown in a broader context, seeing it as a welcome relief following torrid increases over the previous two months, wherein the already-strong gains were revised sharply higher. What’s more, the preliminary 143 thousand increase in payrolls last month is still a solid performance for an economy that is facing mounting headwinds and a swirl of uncertainty.

The Federal Reserve has both types of personalities in its ranks and the latest jobs report is likely to generate ambivalent feelings as well. On the margin, however, it provides further support for the prevailing policy stance of keeping the status quo holding rates steady until a clearer view of inflation and the direction of real activity comes into focus. The prospective trend in both remains clouded in uncertainty, particularly given the dramatic policy events unfolding under the Trump administration, including the still unknown fate of tariffs, deportations, spending cuts and taxes. Over the near term, however, the Fed understandably believes that there is little risk of staying on the sidelines as the job market and the broader economy show no sign of needing help from lower rates.

To be sure, analyzing data for January is always a complicated task, as the beginning of the year generates noisy influences that do not neatly fit into the seasonal adjustment playbook of government statisticians. New wage provisions under revised labor contracts kick in, for example, and weather tends to be more unpredictable. There is also the matter of annual benchmark revisions in January that are incorporated into the data, which distorts comparisons with earlier figures. In this regard, the preliminary data in the latest jobs report will probably look much different in coming months when new information can lead to large revisions. The January report is a startling case in point.

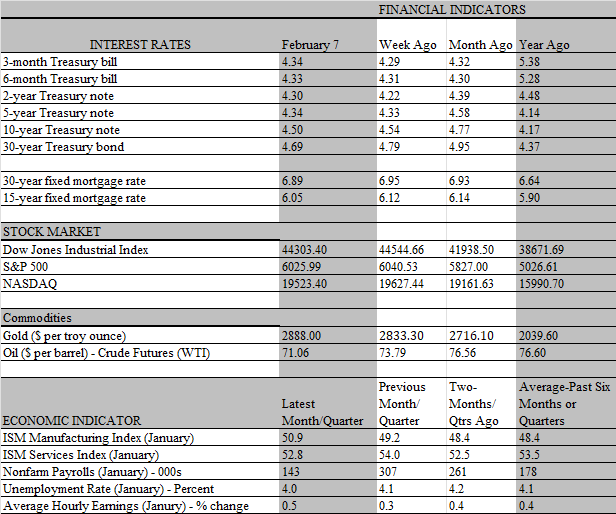

While payroll growth, at 143 thousand, came in below expectations of a 175 thousand increase last month, the estimates for both November and December were revised sharply higher, adding 100 thousand payrolls to the earlier count for the two months. Hence, even with the January slowdown, the trend in job growth is decidedly stronger. The average gain in payrolls over the past three months a better snapshot of momentum shot up to 237 thousand from 204 thousand in December, thanks to the additional headcount to the workforce over the last two months of 2024. Quite possibly, the payroll surge in November and December reflects a rebound from hurricane depressed levels in the fall. But it’s also possible that the January total was suppressed by the California fires and unusually cold weather last month.

Aside from the slower payroll growth, the underlying details of the jobs report for January depict more strength than weakness. The headline-grabbing unemployment rate slipped to 4.0 percent from 4.1 percent, a rate that historically has been consistent with a tight labor market. But that interpretation may not apply to current conditions, as hiring is slowing and layoffs are historically low. Simply put, employers are holding on to workers for a variety of reasons, including fears of labor shortages down the road, particularly if the labor force is decimated by massive deportations. At best, the labor market has been brought into a more balanced state, something that is confirmed by the ratio of job openings to unemployed workers revealed in the Labor Department’s JOLTS survey. That survey the Jobs Opening and Labor Turnover Survey also shows that workers are staying put, quitting at a much-reduced pace because confidence in finding a better position elsewhere has diminished.

Likewise, a surprising jump in worker earnings may not be all that it seems. Average hourly earnings increased 0.5 percent in January, the strongest monthly increase in nearly three years. That bumped up the annual increase from 4.0 percent to 4.1 percent. But that hardly reflects an increase in worker bargaining power, which would clearly ignite inflationary concerns and send the Federal Reserve into a more hawkish stance. The earnings bump comes with two caveats. First, average hourly earnings are influenced by the mix of job changes in any given month. Hence, if more low-wage workers were sidelines by weather or the Los Angeles fires, that could bias the average earnings growth higher. The Labor Department said that the fires had no discernable impact on the employment numbers, but employment in the leisure and hospitality sector swung from a robust 49 thousand gain in December to a 3 thousand contraction in January, a swing that suggest the fires kept at least some diners away from restaurants and bars last month.

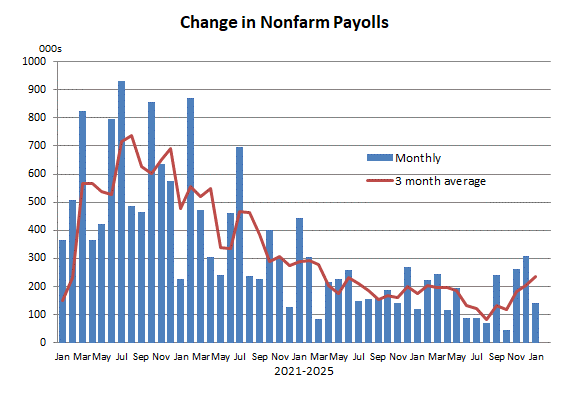

Second, the strength in hourly earnings is not translating into bigger weekly paychecks. The reason: employers are cutting worker hours. The average workweek fell 0.1/hour to 34.1 hours in January, the shortest workweek since the worst of the pandemic recession in March 2020. Before that, you would have to go back to the Great Recession in 2009 to find a shorter workweek. Hence, while hourly earnings increased, the weekly paychecks for nonmanagement workers declined last month. Importantly, it is what’s in the weekly envelope that determines spending, not the hourly rate. The bottom line is that the Fed does not consider wages to be a source of inflationary pressures.

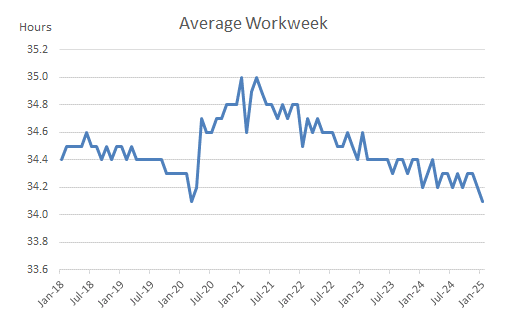

What might influence the Feds thinking, however, are peoples inflation expectations. More than anything this could influence their behavior regarding purchases. If consumers expect higher inflation, they might very well pull forward purchases to beat higher prices, something that would become a self-fulfilling prophecy if demand outstrips supply. One event that would stoke household inflation expectations is headline-grabbing talk of tariffs, and how this will be passed on to consumers. That prospect was on full display early this month, as captured in the University of Michigans household sentiment survey. The widely-followed survey, released on Friday, showed that household year-ahead inflation expectations surged a full percentage point to 4.3 percent, reaching their highest level since November 2023 and leaving expectations significantly above the pre-pandemic range.

However, rather than spurring advanced buying, this time the spike in inflation expectations is acting as a deterrent, sending household sentiment, as well as buying plans for big-ticket items, sharply lower. This comes as no surprise, as consumers have become more judicious in their buying patterns of late, seeking out bargains and generally trading down from expensive to more affordable products. Overall consumption has held up well, and the resilient job market indicates that will continue in coming months, keeping the Fed on the sidelines However, the negative impact that the prospect of tariffs is having on the psyche of households suggests that the economy’s main growth driver, consumers, may be more vulnerable than generally perceived.