A puzzling dichotomy that received much attention last year continues to cause a good deal of head-scratching among economists, namely the wider-than-usual gulf between perceptions and reality regarding the health of the economy. Put simply, a large swath of the population believed the economy was heading for or actually in a recession amid skyrocketing inflation. That perception, of course, clashed with reality, as the economy delivered another solid performance last year and inflation retreated. To be sure, in a highly polarized electorate, political bias contributed importantly to this cleavage between soft and hard data, with Republicans maintaining a gloomier mindset than Democrats leading up the elections and vice versa since the elections.

Unsurprisingly, economists have long put more faith in hard data than in the soft data generated by household and business surveys. The rationale is that the economy�s engine is powered more by what people do, not by what they say. But while downplaying the influence of soft data in general, economists and policymakers pay attention to the expectational component of surveys. The Fed, in particular, attributes considerable importance to inflationary expectations, and their potential to become self-fulfilling prophecies. Hence, even as the disinflationary process stalled late last year and fears of a resurgence grew, the Fed drew comfort from the fact that inflation expectations remained well anchored, keeping the self-fulling prospect at bay.

But amid the statistical distortions that are wreaking more than their usual havoc with hard data this year, the soft data have been garnering more attention and credibility in the eyes of many. Indeed, the financial markets have responded quite dramatically to signs of distress among households that have appeared in two key surveys the University of Michigan and the Conference Board both manifesting a deepening sense of gloom. A similar downbeat mood is sounded among small businesses, which shed all post-election optimism in February.

A common thread behind all the negative soft-data readings is an upsurge in uncertainty surrounding the onslaught of tariff proposals coming from the administration. While the perception that Trump is using the cudgel of tariffs as a negotiating tool to gain concessions from trading partners suggesting that they may be softened, rescinded or postponed it’s become increasingly apparent that many, if not most, of the duties are going into effect. Trump announced another 10 percent on Chinas imports this week and reaffirmed that the 25 percent tariff on Canada and Mexico would go into effect next week. A slew of additional tariff proposals on steel, aluminum, autos, pharmaceuticals and chips are also planned to go into effect in March and April.

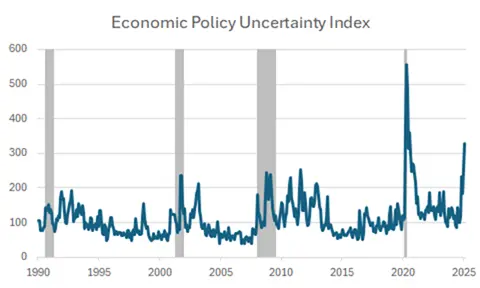

It’s still unclear how much is of the tariff roster will see the light of day or turn out to be bluff; but the uncertainty it has stoked is considerable. According to one popular measure published by the NBER that culls data from 12000 newspapers, the current level of uncertainty over policies is higher now than at the onset of four previous recessions, topped only by the spike during the peak of the Covid downturn. Significantly, the negative thrust behind the upsurge in uncertainty is coming from both sides of the Fed’s dual mandate. The prospect of extensive tariffs is boosting inflation expectations even as it heightens growth concerns. On Google search, interest in the topic of recession has nearly tripled since the start of the year.

That said, the link between expectations and real activity is tenuous, underscoring the notion that it is best to watch what people do not what they say. However, the increasing likelihood that tariffs will be imposed as well as headline-grabbing announcements from business leaders and forecasters that they would boost inflation and prod companies to rethink investment plans and staffing needs indicates that behavioral changes are more likely than not. Clearly, companies have already accelerated plans to import goods before tariffs kick in, as imports of goods surged by a record 12.3 percent in January, blowing past expectations and blowing up the trade deficit to its widest point on record.

While the larger trade deficit will be drag on growth in the first quarter, the spike in imports is more of a timing shift than a permanent change in demand for foreign goods. Hence, the advance stocking up of merchandise in January should be offset by a corresponding decline in imports in February. In the interim, those imports will go into inventory partially offsetting the drag from trade. The question is how long it will it take for importers to clear their shelves, something that depends on the strength of final demand, most notably from consumers. The length of time inventories are held involuntarily will also influence pricing behavior. early days for the hard data to provide evidence of how that will play out, and the recent spate of reports sends mixed signals about evolving trends.

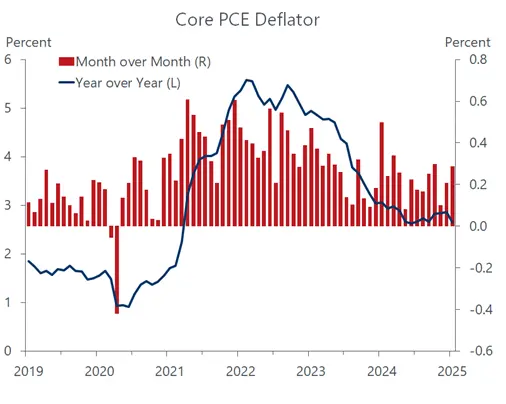

2A key report this week highlights the crosscurrents that are complicating the Fed’s task of navigating its dual mandate. On a positive note, the personal income and spending report revealed that progress on the inflation front was made in January. For the first time in five months, the annual increase in the core personal consumption deflator the Fed’s preferred inflation gauged fell 0.3 % in January to 2.6 percent. That’s still meaningfully above the Fed’s 2 percent inflation target, but the resumed decline indicates that the disinflationary trend has not been stymied. It also dilutes the inflation scare stoked by the hotter than expected consumer price report released earlier this month. The subdued reading in the core and overall PCE deflator both of which increased 0.3 percent over the previous month was generally expected, based on the source data from the CPI and PPI reports. Still, the details were encouraging, as service prices cooled, both with and without housing prices.

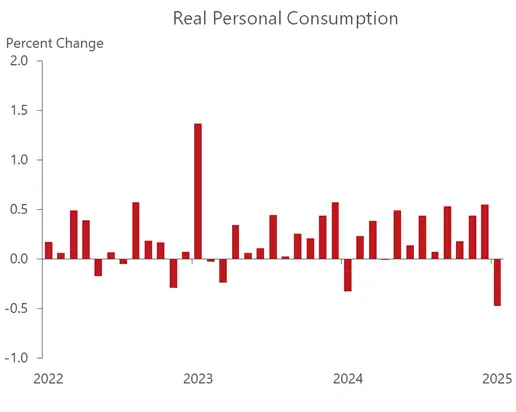

But while the inflation side of the ledger came in as expected, the real side did not. To be sure, consumers were expected to pull in their horns following a robust holiday shopping season and harsh climatic conditions in January. But the spending slump last month turned out to be far worse than expected, as outlays on goods and services adjusted for inflation plunged by an eye-opening 0.5 percent, the steepest monthly decline since February 2021. The good news is that personal incomes staged a solid 0.9 percent increase, matching the strongest gain since July 2021, buoyed by sturdy wage gains and a big assist from interest and dividend receipts, indicating that the wealth effect is still adding heft to balance sheets. The combination of slumping outlays and surging incomes translated into a big increase in the savings rate, boosting it to 4.6 percent from 3.5 percent. We expect that the sustained income gains, healthy balance sheets and the increased firepower from a bigger savings cushion to keep consumers in a spending mood that will power a resurgence in growth following the likely first-quarter slowdown. We also caution, however, that the build up in savings last month could be a precautionary move by households in response to the tariff threat and the more downbeat mindset revealed in recent surveys. In that case, the soft data may be a more telling signal of the future than it normally is.