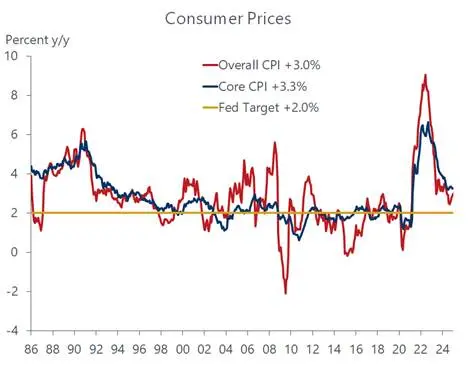

Inflation concerns heated up this week, ignited by reports showing stronger than expected increases in consumer and wholesale prices in January. Unsurprisingly, the attention-getting headlines solidified the growing perception that the Federal Reserve will forgo additional rate cuts for the foreseeable future. The financial markets are priced for no cuts through the spring and summer and see one, at best, by the end of the year. A whisper sentiment that the Fed is just as likely to raise as to reduce rates is also gaining some traction, although that still remains a remote prospect in the eyes of most. Chair Powell at his congressional testimony this week reaffirmed his earlier assertion that the Fed is in no hurry to cut rates. We are looking for one reduction later this year but recognize that the odds the Fed will stay put until 2026 have increased.

That said, there are compelling reasons to believe the initial negative reaction to this weeks inflation reports were overdone, amplified by pending tariffs and the perceived notion they will be passed on to consumers. The disinflation process so firmly underway in late 2023 and over the first half of last year has since hit a wall, but one that is made of soft material rather than bricks. A breakthrough may take longer to occur, particularly if the tariffs cover a wide swath of goods and are passed on to consumers. But that would also incur a consumer backlash, resulting in weaker sales and prompting companies to rescind some price hikes. Odds are there will be less of a 1 to 1 passthrough of tariffs to consumers and the inflation lift will be modest. That together with the ongoing boost in productivity and slowing wage growth should set the stage for lower inflation later this year.

As it is, January’s data are difficult to interpret as the month tends to feature some one-off factors that distort the outcome. The outsized 0.5 percent increase in the overall consumer price index appeared disturbing at first, sending market yields briefly higher, as it exceeded expectations and was the strongest monthly rise since August 2023. A similar pattern is seen with the core CPI, which rose by an above-consensus 0.4 percent, the fastest since last March. But a similar spike occurred last January and the one before, driven in large part by many of the same one-off factors that prevailed this time.

In essence, government statisticians have a hard time seasonally adjusting price changes during the first month of the year, when they are more likely to fall outside of normal calendar changes. This so-called residual seasonality involves prices of some items that are adjusted only once a year, usually in January, to capture higher costs incurred months earlier. Insurance premiums fall into this category of sticky prices, which not only reflect more expensive car repairs incurred in 2024 but must also be negotiated with state legislators before being put into effect. Keep in mind too that some January price adjustments reflect a lagged response of businesses to cover big wage settlements that were negotiated with unions in the fall of 2024.

One way to adjust for the January effect is to compare the outcome with the year-earlier level, pitting apples against apples. This exercise shows that underlying consumer inflation has not changed much for the last six months. True, the core CPI inched up by 0.1 percent in January to 3.3 percent, but the year-over-year inflation rate has remained in a tight 3.2-3.3 percent since last June. The overall CPI has exhibited bigger changes, but at 3.0 percent in January, the annual inflation rate is spot-on where it stood last June. While one-month does not make a trend, a six-month span of steadiness is more reflective of underlying conditions.

No doubt, the Fed is comforted by the absence of accelerating inflation. And with no pressure coming from labor costs, it can readily dismiss hawkish calls to raise rates. Indeed, the source data in the consumer and producer price reports indicate that the increase in the Feds preferred inflation measure the Personal Consumption Deflator slowed in January. That prospect received major support from the producer price report wherein all but one PCE component portfolio management fees fell last month, including a sizeable 0.5 percent in physician fees, a decline exceeded only twice before over the last ten years. As much as anything, the promising reading in the PCE deflator erased the yield spurt that initially followed the release of the CPI report.

Still, the effort to get inflation down to its 2 percent target is proving to be more of a struggle for the Fed than thought a few months ago. With the economy holding up well, there is no compelling reason for it to cut rates sooner rather than later. Even with the January price spike, workers are keeping pace as real average hourly earnings were unchanged last month, retaining the gains made over the past two years. To be sure, not all segments of the population are keeping up. Lower income households are feeling more of a pinch from inflation than wealthier cohorts, as they spend more of their paychecks on necessities. Those include groceries, which features a skyrocketing increase of more than 50 percent in egg prices over the past year, punctuated by a 15.2 percent increase in January alone. Overall, the 0.5 percent increase in grocery prices last month was the largest in two years.

Of course, the Fed could do nothing about the main culprit driving up egg prices the bird flu; what’s more, the budgetary squeeze on households from more expensive eggs may be somewhat moot since there are hardly any to buy as destroyed infected chickens are keeping them off grocery shelves. Instead of selling them by the customary dozen, many grocers are packaging them for sale in twos and threes; it will be interesting to see how those sales prices are captured in the seasonal adjustment process. In addition to the bird flu, several other external shocks the devastating California wildfires and unusually cold weather also upended data for January, making the Feds task of separating the noise from the signal that much harder.

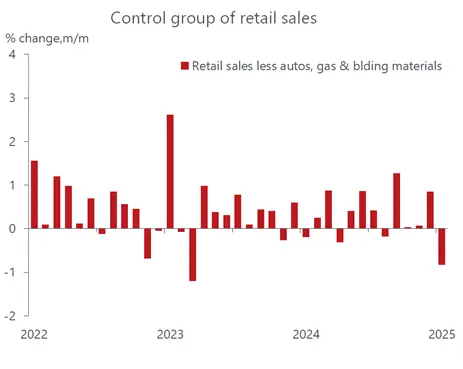

Fridays retail sales report is a case in point. Like the inflation reports, this one too fell well outside of consensus expectations. The 0.9 percent plunge in overall sales was about twice as severe as expected; it was also greater than the rise in prices during the month, meaning that most of it was in real terms. The question is, was the drop merely a post-holiday slump following the robust sales during the holiday season, or something more fundamental? Clearly, the wildfires and cold weather had an effect, which will be temporary, keeping consumers indoors rather than shopping. But that would not explain the sharp drop in online sales, and the whopping 4.6 percent slump in discretionary purchases sports, hobbies, books and music suggests that the weakness extends beyond low-income households.

Importantly, the control group of sales that enter the GDP calculations staged the biggest decline since April 2023, indicating a slow start for the economys main growth driver in the first quarter. We do think that the setback is temporary, and sales may well be revised higher when more complete data are available in coming months. Except for the low-income cohort, household balance sheets are in good shape and the sturdy job market should keep real income rising, providing the firepower to sustain a solid pace of consumer spending. Simply put, the latest batch of data provides more evidence for the Fed to stay on the sidelines, particularly considering the uncertain trade and fiscal policy environment that lies ahead.