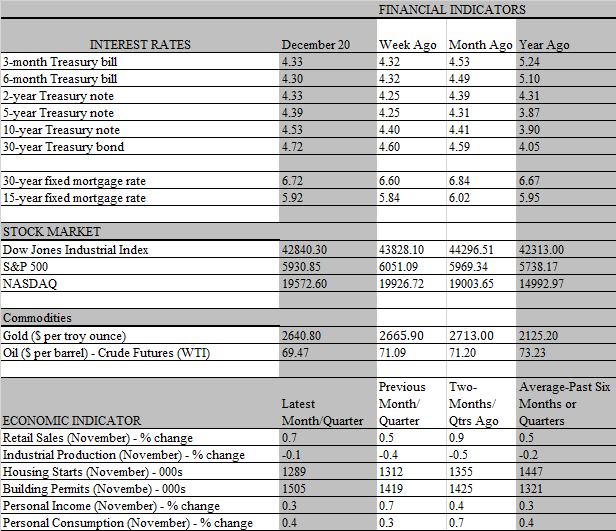

The financial markets are still reeling in the aftermath of the hawkish rate cut by the Fed this week. Stock prices plunged on the day of the Fed meeting on Wednesday and continued to drift lower until a fresh set of positive figures stoked a rally on Friday. Meanwhile, bond yields turned sharply higher, continuing the unsettling trend since September when the Fed put through the first of three rate cuts, culminating in this weeks quarter-point reduction. The latest move leaves the target range for the benchmark federal funds rate at 4.25%-4.50%, bringing the cumulative decline since September to 1 percentage point. Conversely, bond yields, as represented by the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield, has been the mirror image of the funds rate. As of Friday, the yield stood at just over 4.50%, up nearly a full percentage point from the 3.62% on the day of the Feds September rate-setting meeting.

No doubt, a looming government shutdown over the weekend added to the markets turmoil this week. But the overriding influence was clearly the Fed meeting, particularly the signal that it will cut rates fewer times in 2025 than planned in September, the last time it issued its quarterly Summary of Economic Projections (SEP). Three months ago, the median forecast of Fed officials was for four cuts next year; now that number has been pared to two. Indeed, one official of the rate-setting committee, Cleveland Fed President Hammack, was even more hawkish, preferring to leave the target rate for the funds rate unchanged this week.

The decline in the number of rate cuts forecast for next year is not surprising. While the policy statement and Fed Chair Powell at his press briefing said the FOMC views the risk to the outlook as “roughly in balance,” the Fed seems more focused on inflation not declining as quickly as previously forecast than it is concerned about the health of the labor market. Hence, policy makers marked up their forecast for inflation, particularly for 2025, to 2.5 percent from 2.1 percent at the September meeting. On balance, our takeaway from the policy statement and Powell’s presser is that, while Fed officials are still mostly confident that inflation is heading back to target, it is happening slower than previously expected. Moreover, while the labor market has softened the Fed believes it is still healthy overall and can tolerate a slower pace of rate cuts, particularly since 1 percentage point of policy restriction has already been removed.

It’s unclear how much of an influence the policy proposals of the incoming administration had on the Feds more hawkish mindset. In November, Fed Chair Jerome Powell said about policy decisions resulting from the election outcome, “We don’t guess, we don’t speculate, and we don’t assume.” However, this week, he noted some participants started to “incorporate highly conditional estimates of economic effects of policies into their forecast at this meeting and said so in the meeting.” At the post-meeting press conference, Powell also said fiscal policy uncertainty was one reason some members became more uncertain about the inflation outlook.

We suspect that if Trump successfully implements the aggressive tariffs he is espousing as well as the massive deportations proposed on the campaign trail, inflation expectations will increase markedly, not only by Fed officials but on both Wall Street and Main Street. As it is, there are signs that behavioral changes are already taking place, as businesses and households are reportedly stepping up purchases and booking orders early to lock in prices before tariffs kick in next year. To the extent that is happening, it may well be juicing activity now at the expense of next year, when a payback in the form of weaker spending could set in. While such a scenario is still mostly speculation, it may be no coincidence that the economy’s main growth driver is firing on all cylinders.

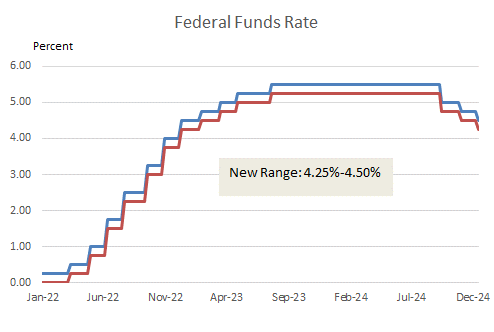

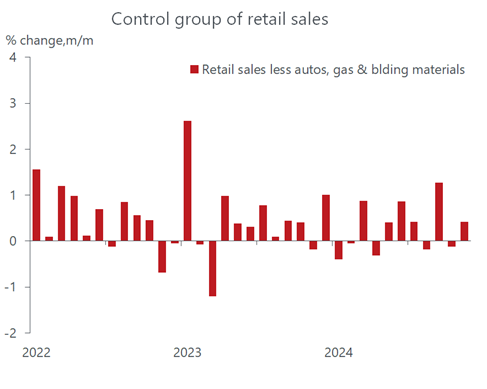

That was clearly in view this week as a pair of reports on household activity revealed that consumers are keeping their wallets wide open. The first, on retail sales, showed that the demand for goods was stronger than expected. Retailers reported a solid 0.7 percent increase in sales in November, topping consensus forecast of a 0.5 percent advance. True, the spending pickup was heavily influenced by an outsized increase in auto sales, reflecting the expected strong demand for replacement vehicles that were destroyed by Hurricanes Helene and Milton. But even excluding autos, sales rose by a robust 0.4 percent, which was double the expected gain. Importantly, the so-called control group of sales that feed directly into the GDP accounts rebounded from the mild setback in October, increasing by a solid 0.4 percent. The one cautionary note in the retail sales report was a pullback in spending at bars and restaurants, the sole category of services in the report, leading to speculation that the much larger services sector of the economy might be sputtering.

However, that concern was abruptly erased with the release of the second consumer-related report this week, the more comprehensive personal income and spending report, which covers outlays on services as well as the goods contained in the retail sales report. As expected, the surge in replacement auto sales also boosted the overall spending figure, but outlays on services did not skip a beat. Despite the drag from restaurants and bars as well as from a decline in sales at gas stations, most service providers recorded sales gains, with recreational services leading the way. Indeed, spending on recreational services staged the biggest inflation-adjusted increase in November, 1.2 percent, since June 2023. With data for October and November now in the books, real personal consumption is on track to grow by a hefty 3 percent annual rate in the fourth quarter.

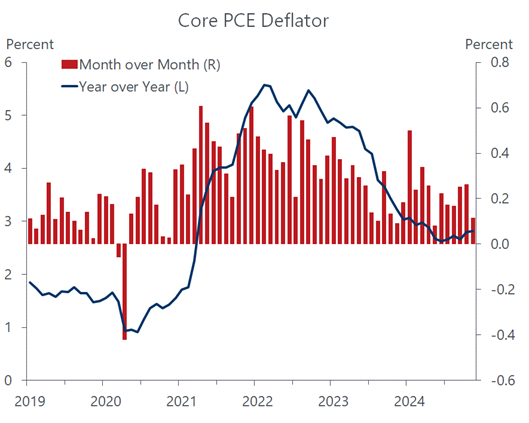

Hence, with solid consumer spending still driving economic growth, the Fed understandably has become less concerned about a faltering economy that might justify steeper rate cuts. But what the latest personal income and spending report also shows, is that the Feds inflation concerns might be overblown. As much as anything, the subdued increase in prices revealed in that report sparked the sharp rally in stock prices on Friday. Simply put, the Feds preferred inflation gauge, the core Personal Consumption Deflator, increased by the slimmest amount in November since the spring. While this measure remains well above the Feds 2 percent target, increasing 2.8 percent from a year ago, there is little evidence that inflation is reaccelerating. However, the Fed is unhappy with the slow progress it is making towards the target and given the economy’s resilience, it will likely skip another rate cut in January.

At the time of publication, it was not clear whether Congress would be able to avoid a partial government shutdown, with the House of Representatives set to vote later on Friday on a continuing resolution, along with disaster relief for hurricane victims and aid for farmers. Up until this point, lawmakers have been unable to agree upon a continuing resolution that would fund government operations into mid-March. If the government shuts down over the weekend but lawmakers pass a short-term funding bill by Monday, the economic impact will be negligible. Even a weeks-long shutdown would only have a modest effect on the aggregate statistics. A five-week partial shutdown that started on December 22, 2018, and ended on January 25, 2019, was estimated by the Congressional Budget Office to have only reduced the level of real GDP by 0.1% in the fourth quarter of 2018 and by 0.2% in the first quarter of 2019.