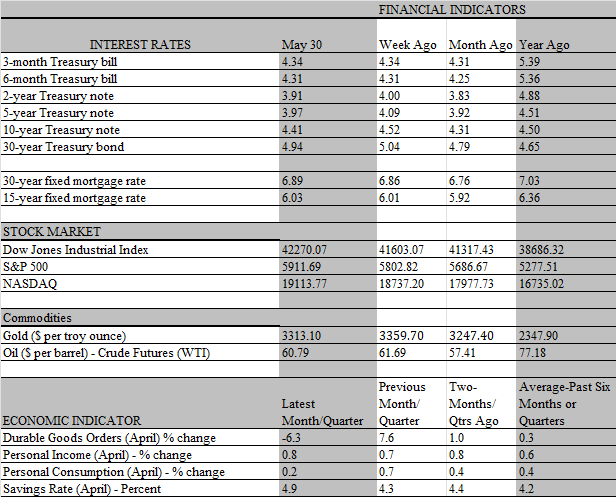

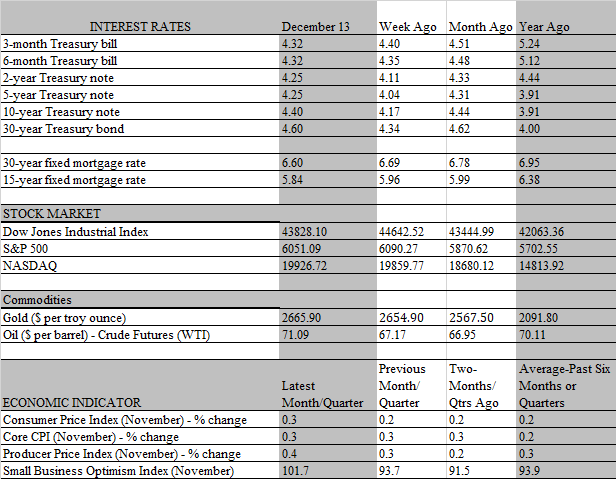

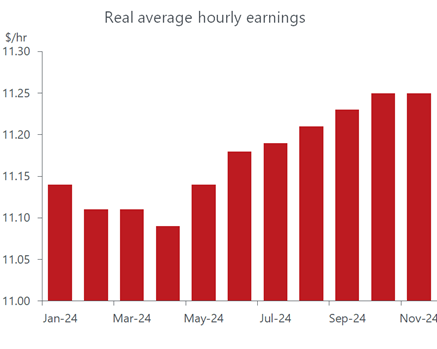

The tail-end of the holiday shopping season is rapidly approaching; by all accounts consumers are in a festive mood, keeping their wallets open and purse strings loose. But for the first time in seven months, they did not have extra purchasing power in November to shop with, as prices at the retail level rose by the same amount as worker earnings. Thats the first time since April that real worker earnings failed to increase from month to month. To be sure, one size does not fit all when it comes to measuring inflation and its impact on consumption. The 0.3 percent increase in the consumer price index during the month masks disparate price changes that impact the budgets of low-income households differently than those higher up the income ladder. Prices of medical care and food purchased for home use, for example, rose at a faster 0.4 percent during the month, which is more meaningful for lower-income households and seniors. By the same token, the relatively stronger 0.4 percent increase in airline fares reflects increased demand for travel, which is a discretionary expense incurred mostly by wealthier individuals who are better equipped to afford the higher prices.

Likewise, the 0.3 percent increase in average hourly earnings, as tracked in the Labor Departments jobs report, masks wide disparity among occupations, even as the average increase itself reflects the varying influence that high versus low-earnings jobs has on payroll growth. Mirroring the increased demand for travel, for example, a big 60 thousand swing in job growth between October and November occurred in the high-paying financial and business and professional service occupations. While lower-paying leisure and hospitality jobs also increased strongly last month, that was largely offset by a sizeable decline in jobs in retail, which mostly employs lower paid workers.

From a macro lens, the pattern of price and wage growth last month echoes the major forces driving the economy’s engine. Consumers are the key cylinder propelling growth, and higher-income households are the pistons generating most of its power. Their outsized contribution is likely to continue, thanks to a formidable financial cushion buoyed by surging stock prices and housing equity. What�s more, that cushion is undercounted, as the nearly $3 trillion in cryptocurrencies held mostly by wealthy investors are not considered a financial asset by the Federal Reserve. Some believe that covert wealth is propping up sales of luxury goods, highlighted by the banana art piece that recently sold at auction for over $6 million.

And despite misgivings over the potential adverse effects of higher tariffs, household and business confidence has improved significantly since the election. While the link between confidence and behavior is not particularly tight, the improving mindset does impart an upward bias to hiring, business investment and consumer spending in coming months. We expect the economy to turn in another solid performance in the current quarter, with real GDP slowing only modestly from the robust 2.8 percent growth rate in the second quarter and remaining on an above-trend growth path throughout 2025.

Of course, this optimistic assessment assumes that external shocks or policy missteps do not derail the economy’s growth engine. That’s always a bit of a stretch, particularly in a combustible global environment, where military conflicts abound, political upheavals, most recently in Syria, threaten alliances, which, along with unforeseen climatic events, can once again disrupt supply chains. Fortunately, the U.S. economy has so far weathered these external shocks, further displaying the resilience it has long exhibited. Since such shocks defy predictions, all eyes are on upcoming decisions of policy makers, which can make or break promising expectations for the economy.

The fiscal side is a work in progress that will take months to play out as the incoming administration provides details of its plans for tariffs, taxes, and deportation and to what extent they will actually be implemented. More immediately are the rate-setting decisions of the Federal Reserve, including the one that will be made next week. Most believe that the outcome is already baked in, as the financial markets are fully priced for a quarter point cut at the conclusion of the December 17-18 meeting. Any different outcome could be highly disruptive to market conditions, which the Fed usually tries to avoid.

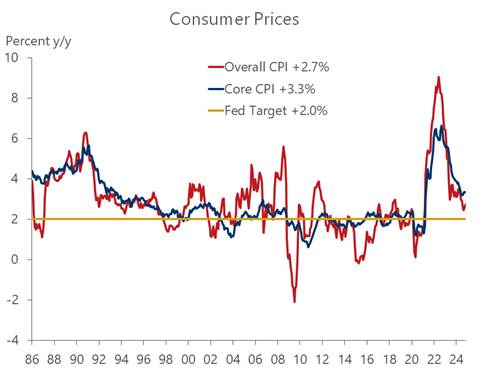

That said, while the consensus agrees that a rate cut is coming, not all agree that it is justified. As noted, the economy is still chugging along and the need to stimulate activity by lowering rates is not considered urgent. Meanwhile, inflation is proving to be stickier than earlier expected, which bolsters the argument that the Fed should pause until there is more evidence the disinflation trend is still unfolding. The latest consumer price report would seem to support the more hawkish sentiment. Although the details were mostly expected, this is one instance where expected outcomes still led to disappointment. Simply put, the report reaffirmed the slow progress the Fed is making in wrestling inflation down to its 2 percent target. The headline CPI increased 2.7 percent in November from a year ago, up from 2.6 percent in October, while the core CPI increased 3.3 percent for the third consecutive month. Indeed, the core CPI is the poster child of stickiness, having increased 0.3 percent in each of the past four months.

Still, there were some bright spots on the inflation front that give the Fed leeway to cut rates next week. For one, housing costs the major component keeping inflation sticky are finally showing signs of easing. Both tenant rents and owner-occupied rents recorded the smallest monthly increase in November in more than three years. One month does not make a trend, of course, but there is good reason to think the easing trend will continue based on current lease signings. Also, a big jump in used car prices last month reflected strong replacement demand for autos destroyed by Hurricanes Helene and Milton, which is not likely to be sustained. Importantly, unlike the stickiness of the CPI, the personal consumption deflator � the Fed�s preferred inflation measure is expected to show a slower increase in November, based on the source data contained in the CPI and PPI reports this week.

We believe that the disinflation trend has temporarily stalled, not stopped. The road to the 2 percent target is turning out to be bumpier than the Fed would like, but the rebalancing of the labor market, a pickup in productivity and slower wage growth will take more steam out of inflation in 2025. The odds that the Fed will skip a rate cut in January has increased owing to the stubborn inflation readings in recent months; but real rates are still restrictive, and more cuts will be needed next year to keep the economy afloat.