First impressions are never a good look in economics. Not only do they often mislead investors, but they can also spur misguided efforts to influence policy. That notion was on full display the past two weeks, reflecting the markets dramatic knee-jerk reaction to a surprisingly weak jobs report last week that subsequent data suggest may be nothing more than a head fake. Still, the first impression delivered a wallop, sending stock prices and bond yields plummeting temporarily as recession fears spiked in the days following the release of the report.

Never mind that the report itself wasn’t as catastrophic as the headlines made it out to be. The markets’ jitters were more about direction than levels, and the upward move in the unemployment rate along with the softer- than -expected pace of job creation in July signified to many that the momentum towards recession was gaining traction; even worse, sentiment grew that the Fed was falling too far behind to stop the bleeding. Indeed, the grim initial reaction heightened speculation that the Fed would need to cut rates more deeply in September than thought two weeks ago, with many commentators predicting a half point reduction rather than a quarter point cut. Some even wondered if policy makers would take an emergency move prior to the scheduled policy meeting in mid-September, something that rarely happens outside of an external shock to the economy.

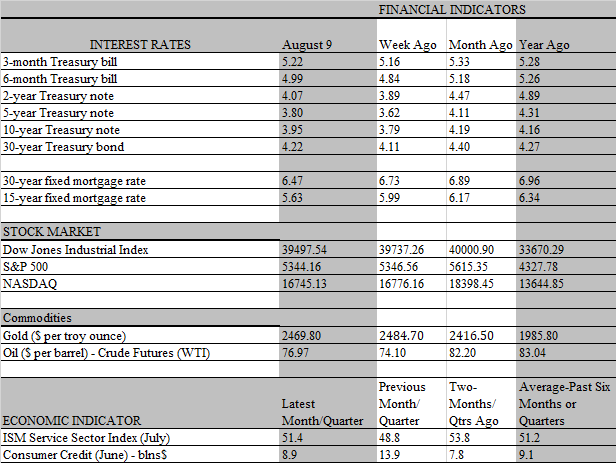

But the road to doomsday encountered speed bumps this week that abruptly wiped away the tears of investors. First, a report by purchasing managers in the service sector, by far the largest contributor to economic activity, staged a solid rebound in July, lifting the overall index of activity back above the 50 threshold that separates expansion from contraction. Importantly, the employment component of the ISM index rose to the highest level since last September. To be sure, the upbeat report released on Monday had only a muted positive impact on the markets, as the survey is considered “soft” data that generally does not move markets. Still, it short-circuited the doom and gloom mindset in the markets and provided an important signal that the labor market was not falling to pieces.

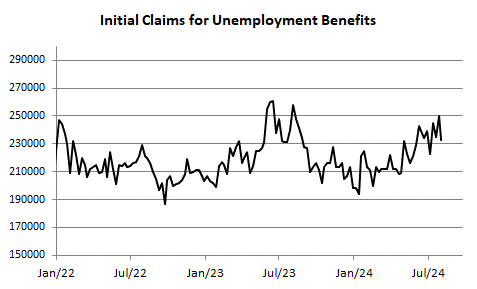

Such assurance was further bolstered on Thursday when the Labor Department reported a sizable drop in initial claims for unemployment benefits in the week ending August 3, reversing the previous week’s spike that fed speculation the job market was tanking. At it turns out, the previous spike was heavily influenced by two temporary factors: Hurricane Beryl which contributed to a big rise in claims in Texas and summer auto plants shutdowns in mid-July. Both faded from the claims data later in the month, and initial applications fell by 17 thousand in the latest week, more than erasing the 15 thousand climb in the previous week. The giveback calmed market jitters, and stock prices rebounded strongly following the release of the claims data. The S&P 500 index notched its biggest gain since November 2022 on Thursday. By the end of the week, stock prices were virtually back to where they were when the week began.

That said, just as the temporary jump in unemployment claims exaggerated the weakness in the labor market, it would be a mistake to read too much into the latest week’s drop. There is a lot of noise in the weekly claims data, so it is best to take a longer-term perspective. Looking at the four-week averages, the trend is moving decisively higher, albeit the level of claims remains comfortably below the recession threshold. Over the past six business cycles, a recession has never started before initial claims for unemployment insurance rose above 300 thousand. The current four-week average, at 240 thousand is still a distance from that inflection point. It’s even further below when viewed against the current much larger labor force that prevailed in the earlier cycles.

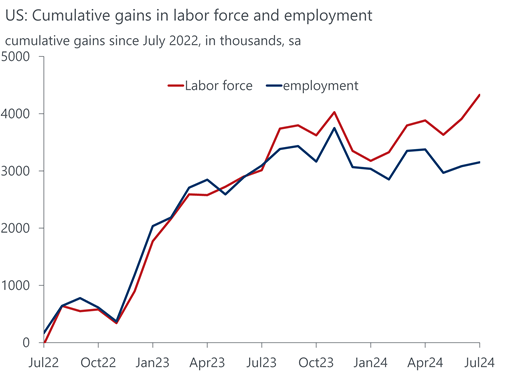

The subdued level of unemployment claims is important because it reflects a significant feature of unfolding developments in the job market. Simply put, labor conditions are softening, but not because companies are laying off workers on a massive scale. Instead, hiring is slowing even as the labor force continues to expand. Indeed, the rise in the unemployment rate over the past year, from a low of 3.4 percent to the current 4.3 percent is due entirely to the faster growth in labor supply than in the demand for workers. While a rise in the jobless rate of that magnitude has in the past always coincided with a recession, as embodied in the so-called Sahm Rule, most economists believe it is not the case this time. That’s because past increases in the unemployment rate were driven by layoffs whereas this time it is driven more by the increase in the supply of labor. People are entering the labor force in droves, but it is taking longer for them to find a job, which is lifting the unemployment rate.

That’s not to say that the upward drift in unemployment now underway is something to be ignored or even downplayed. For one, the jobless rate usually rises slowly early in a recession but then accelerates as the downturn gains traction. It’s possible – but not likely – that a stealth recession has already started, and the job market will follow a similar path as in the past. For another, even if layoffs are low, the longer it takes for new entrants to the labor force to find a job, the more insecure job holders will become. As it is, fewer workers are quitting their jobs and companies are rescinding their job listings. Over time, this could lead to a negative feed-back loop wherein job insecurity prompts workers to reduce spending and the reduced spending leads companies to cut back further on hiring or, worse, start to downsize their workforces. This would be a recipe for a looming recession.

The good news is that household spending continues to hold up and profit margins are still healthy, prompting companies to hold on to staff. The bad news is that cracks are opening on both fronts which could have recessionary consequences if not dealt with soon. Consumer spending is being driven mainly by upper-income households who have more job security and whose balance sheets are flush with the wealth gains from rallying stock prices and home values. But as the past week makes abundantly clear, the stock market is highly fickle and housing wealth is not easily converted into spendable funds. With the job market softening, households higher up the income ladder are reportedly behaving more like their less-wealthy brethren, seeking out cheaper products and scaling back discretionary purchases.

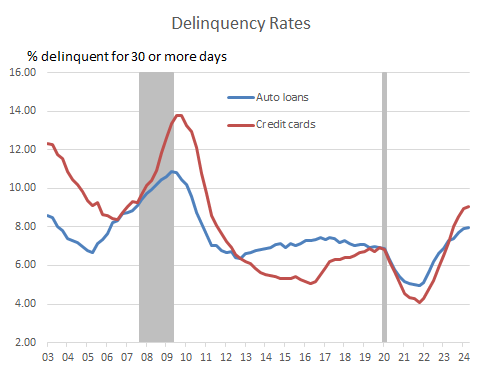

Meanwhile, lower-income households are feeling the pain of high interest rates and elevated prices, which have pushed them more heavily into debt that is becoming ever-harder to maintain. According to the latest NY Fed data, the share of auto loans that are more than 30-days past due rose to 7.95 percent in the second quarter, the highest since 2010. Likewise, the delinquency rate on credit cards climbed to 9.05 percent, the highest in about 12 years. This cohort needs to rely heavily on paychecks to service debt and sustain living standards, which makes continued job growth imperative and lower interest rates necessary to provide welcome relief to struggling borrowers. From our lens, this cements the prospect that the Fed will cut rates at its September policy meeting. We do not believe conditions are dire enough for more than a quarter-point reduction initially, followed by a similar cut in December. But there are still two more inflation reports and another monthly jobs report before the next policy meeting, which could have a major bearing on the Fed’s decision.