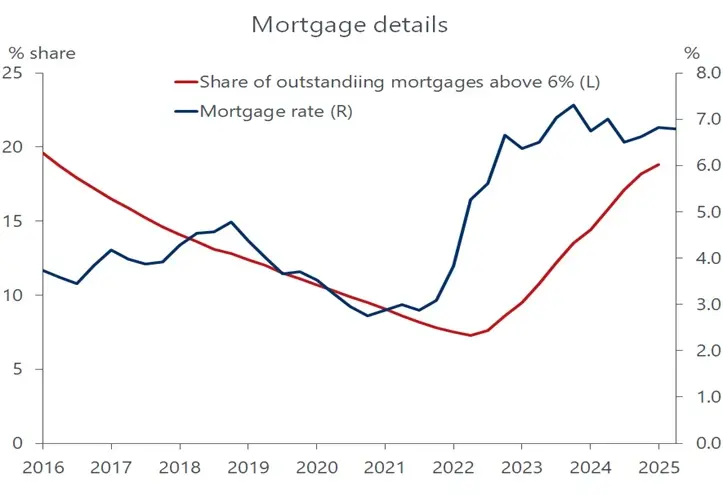

The political maelstrom following the surprisingly weak jobs report last week has subsided, but the shift in perceptions regarding monetary policy and, importantly, the economy’s performance remains intact. Until recently, the U.S. economy has been widely hailed for its resilience, bucking the myriad headwinds from tariffs, the geopolitical tensions they created, downbeat consumer confidence and a host of other soft economic data portrayed by surveys of large and small businesses. Now the economic landscape looks more fragile with the weakness long signaled by soft data seeping into the hard data. The July jobs report followed discouraging data on consumer spending, putting the spotlight squarely on the economy’s two main pillars. If both fall by the wayside, the odds of a recession would increase exponentially.

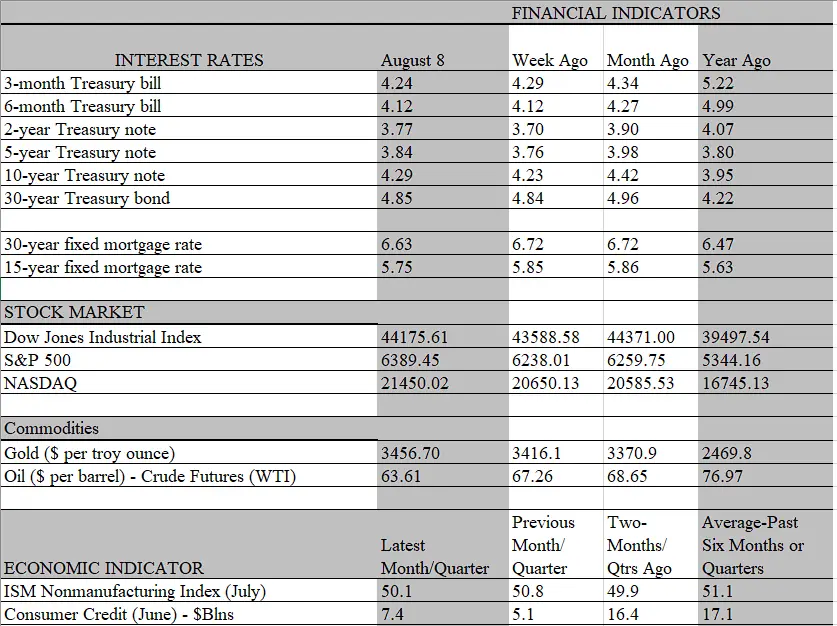

We don’t think that will be the case, as the headwinds buffeting the economic backdrop has injected more noise into the data than usual. That said, the economy is clearly moving into a weaker phase; tariffs are taking a bite out of real incomes and hiring as well as some investment plans are being put on hold until more clarity on the trade front comes into focus. Restrictions on labor supply caused by fewer immigrants entering the workforce are keeping the unemployment rate low, but jobless workers are staying on the unemployment lines longer. Ongoing claims for unemployment benefits are moving steadily higher, reaching the highest levels since November 2021 in the latest week. That may not impact the earnings of jobholders, but it does impact their feeling of job security, making them more likely to save than spend out their paychecks.

At the same time, perceptions regarding monetary policy have shifted markedly since the latest jobs report. The question is not whether the Fed will cut rates sooner rather than later, but how much sooner. The betting in the markets is that September is the odds-on favorite to see the first of two cuts this year. While we still see more reasons for a delay – inflation is moving up and the economy is not as weak as the jobs data suggest – the shift in perceptions is understandable. As is its wont, the markets are pricing in a pending cut, with the stock market taking a bullish turn, sending prices sharply higher, and market yields drifting lower. An easing of financial conditions complements Fed intentions, providing the economy with a shot in the arm before the actual follow up takes place. Indeed, the market reaction has more of an impact on the economy than the Fed’s confirming rate cut.

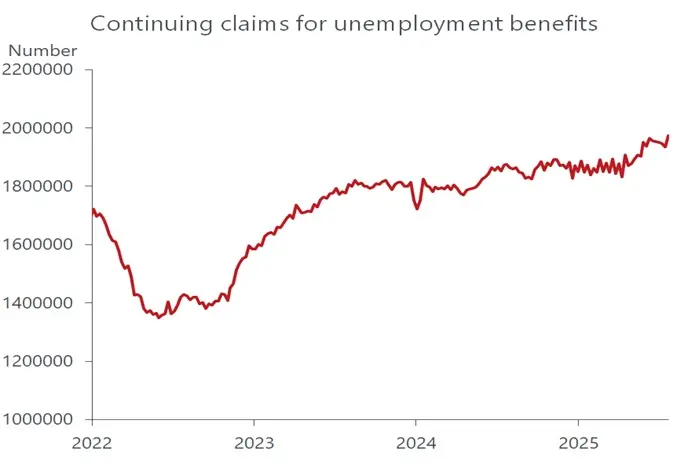

One industry that may soon benefit from lower rates is housing, where sales have been frozen by the reluctance of homeowners to give up their low-rate mortgages by putting their property on the market. Mortgage rates slipped again this week, continuing an erratic decline that leaves it at the low for the year. At 6.63 percent, it is not dramatically below the nearby peak of 7.04 percent reached in mid-January. More important is that it is far above the 3-4 percent that millions of home buyers were able to obtain in the decade following the Great Recession. It would take a considerably steeper fall for them to move off the sidelines.

But the share of mortgage holders locked in with those rock-bottom rates is steadily shrinking, as the number of buyers taking out higher rate mortgages over the past five years has grown. According to recent FIFA data, the share of mortgages outstanding with rates above 6 percent has risen to almost 20 percent in the first quarter, more that double the share that prevailed at the outset of the rate climb that began in late 2021. That share undoubtedly increased in the second quarter. We note that at the current sales pace, the number of unsold existing homes matches the highest level since November 2015. Add the shadow market that would become available if locked-in owners put their homes on the market, and that number increases substantially. Importantly, given the increased share of homeowners with mortgages above 6 percent, it would take less of a decline in mortgage rates than a year ago to unlock those sales.

To be sure, the sale of an existing home does not boost GDP, as the transaction is mainly a transfer of assets. But the secondary effects on growth would be considerable. For one, it would have a spill-over impact on new residential construction, which does boost GDP as well as the demand for labor. For another, the transfer of a home causes ancillary spending on home furnishings, renovations, moving expenses, appliances and a host of other needs that a home buyer spends on. What’s more, even if a homeowner stays put, lower rates could unleash a wave of refinancing activity among home buyers who took on the more expensive mortgages in recent years. Some portion of the refinancing would be of the cash-out variety, wherein borrowers take out a larger loan than the mortgage, transforming their housing equity into cash that can be used for spending purposes.

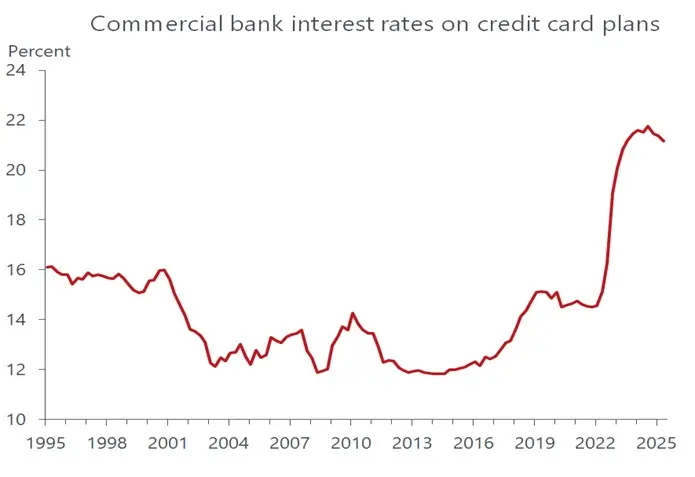

It remains to be seen when the Fed follows through with the expected rate cut and, importantly, how the markets respond in the face of tariff-induced rising inflation. Keep in mind that the mortgage-linked 10-year Treasury yield may or may not continue to retreat in the wake of a Fed rate cut, as it responds more to market forces than Fed actions. However, other lending rates, on auto loans and credit cards, are more responsive to Fed rate decisions, as they are linked to changes in short-term rates that are aligned with the Fed’s policy rate. Following the one percentage point cut in the federal funds rate last fall, rates on credit cards have come down from their nose-bleed levels reached in the summer of 2024. But at over 20 percent, they remain historically high and prohibitively so for struggling low-income households, who are already falling behind on loan payments.

Keep in mind too that the demand for mortgage and consumer loans represents one side of the credit ledger. The other side is the willingness of banks and other lenders to accommodate that demand by making the funds available. According to the latest Fed Survey of Senior Bank Lending Officers, the task of getting a loan has become harder for consumers, as banks tightened standards for credit card loans in the second quarter. This no doubt reflects the rise in delinquencies and dimming job prospects for younger households who are more likely to need borrowed funds to tide them over. The good news is that high net worth Americans, stoked by rising wealth, should continue to buffer the economy until the Fed lends a helping hand with lowered rates and the fiscal stimulus provided by the One Big Beautiful Bill kicks in next year.