The weekly will not be published over the Labor Day weekend. The next issue will be September 6, the day the August employment report is released.

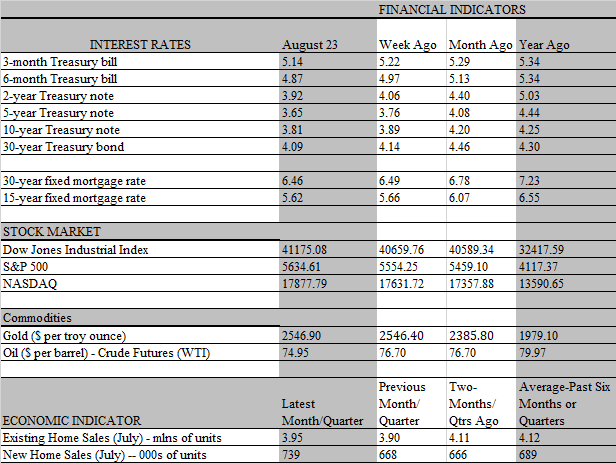

While this week featured a light calendar of economic data, it was not without attention-grabbing news on the political and economic fronts. Unsurprisingly, Kamala Harris’s acceptance speech at the Democratic nominating convention garnered the largest national audience. But the most anticipated and consequential speech for global investors was delivered by Fed chair Jerome Powell at the annual Jackson Hole symposium on Friday morning. To be sure, no one expected earth-shattering news that would jolt the financial markets with a surprise announcement. Powell stayed on script, confirming the widely accepted view that rate cuts were coming, most likely starting at the September 17-18 policy meeting, as the Fed is shifting its priority away from tamping down inflation towards propping up a sagging job market.

But the confirmation, as highlighted by the statement, the time has come for policy to adjust, was enough to ramp up the positive vibes in the financial markets, ending stock prices sharply higher and market yields lower. The only question that remains is how much of a cut is likely to be taken at the meeting. We suspect that even Fed officials to not have firm convictions. No doubt, two key economic reports that will be released prior to the meeting -the employment and CPI reports for August- will have a consequential influence. The odds slightly favor a normal quarter point reduction in the benchmark rate from the current 5.25%-5.50% range, but if the employment report comes in weaker than expected, the odds of a half-point cut would certainly increase.

One reason for the heightened sensitivity over the upcoming jobs data was the startling news this week that the economy generated an eye-opening 818 thousand fewer jobs in the year through March than initially thought. This revision, based on more complete information in the annual benchmark review by the Labor Department, is the largest since 2009. It also confirms what Powell and his colleagues have been noting for some time, that the robust monthly payroll numbers over that time span has been overstating the strength in the job market. That said, even with the downward revision, the 174 thousand average monthly increase in payrolls over that 12-month period is a healthy pace of job creation.

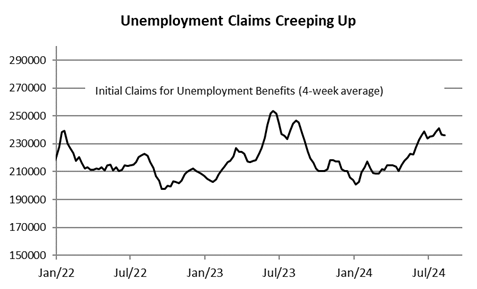

Since March, the growth in payrolls has downshifted further, to a monthly pace of 154 thousand, Meanwhile, the unemployment rate has been creeping up, with the rise from 4.1 percent to 4.3 percent in July triggering the so-called Sahm Rule, which implies that the economy is already in a recession. That’s not the view held by most economists or the Fed because the climb in the unemployment rate has been driven by an expansion in the supply of labor not by layoffs, which typically happened in past recessions. What’s more, the 4.3 percent jobless rate is still low by historical standards.

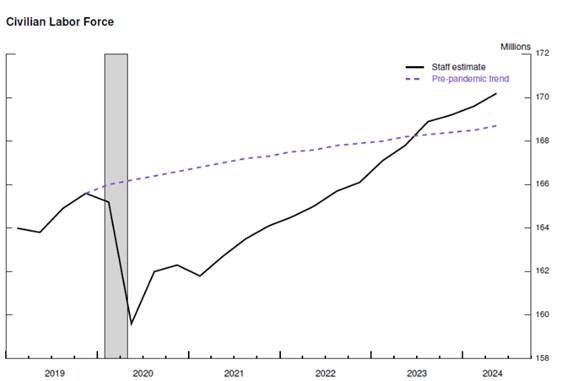

That said, the unemployment rate is a flashpoint that could become more of an issue with the Federal Reserve if it continues to rise in a meaningful fashion. Unlike the revisions to the payroll figures, the unemployment rate won’t be revised until January when the government releases new population estimates. One of the more interesting features that received little notice in Powell’s speech on Friday was a chart showing the Fed’s projections of the labor force, which shows a climb that far exceeds the prepandemic trend. No explanation was given for this by Powell, but we suspect that the Fed’s staff is belatedly taking into account the rapid rise in immigration that may not be fully accounted for in the current jobs data.

Importantly, past periods of rapid immigration caused large revisions to household employment and the size of the labor force. The same is likely to be true this time around. Because recent migrants are more likely to be unemployed, the pattern of revisions could push unemployment up as well. For example, the 1990 census resulted in upward revisions to the unemployment rate, as estimates of the Hispanic population were revised sharply higher, a group that experienced significantly higher rates of unemployment. If the new labor force projections by the Fed turns out to be correct, it would require a stronger pace of job growth to keep the unemployment rate level. Until now, a trend payroll growth of 110 thousand was thought to be consistent with the increase in the labor force. Under the new projections, that breakeven rate would rise to about 200 thousand.

That said, the upward revisions to the labor force makes clearer that the recent increase in the unemployment rate is mostly supply-related. It also explains why the unemployment rate is rising even as job growth remained at a relative healthy 170 thousand over the past three months. Although it would make for a healthier economy if the new entrants to the labor force found a job more quickly, thus keeping the unemployment rate steady, the Fed would be more deeply concerned if the increase in the unemployment rate were driven by layoffs rather than by a faster growth in the supply of workers than the economy could handle.

So far, that has not been the case. Companies have been holding on to full-time staff as much as possible, partly due to the lingering recollection of labor shortages in 2021 and 2022, but mostly due to the still sturdy pace of demand, which supports the revenues needed to cover labor costs. The jump in initial claims for unemployment benefits in late July turned out to be caused by Hurricane Beryl, which temporarily shut down businesses in Texas. That spike has since been reversed, but claims are still noticeably higher than they were before the hurricane set in. The Fed will no doubt keep a close eye on this trend, as an acceleration in applications for jobless benefits would signify that companies are indeed downsizing and laying off workers.

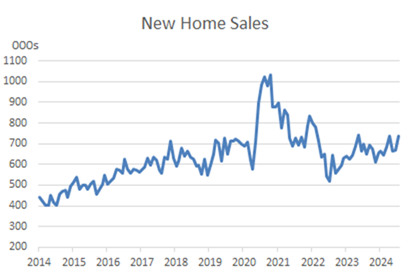

We believe that the job market is cooling, but mostly due to softer hiring rather than massive layoffs. Companies have rescinded job postings and are not filling open positions as quickly as before. This trend, of course, has a positive attribute in that it contributes to a slowdown in wage growth and, hence, inflation, opening the door wider for the Fed to start cutting rates. As the rate-cutting campaign gets under way – we expect quarter=point cuts in all three meetings over the remainder of the year – the economy should receive a jolt of energy, particularly among the rate-sensitive sectors, like housing. In anticipation of that prospect, mortgage rates have already fallen by more than a half percent from its peak this spring, adding some heft to home sales. Importantly, lower rates will make it easier for the financially strapped lower-and middle-income households to service credit card balances, where delinquencies are rising. That should go a long way towards keeping a floor under consumer spending and keeping the economy out of a recession.