The Federal Reserve is a deliberative body that does not have the audacity to declare “mission accomplished” in its quest to achieve a soft landing. But it can justifiably savor the sweet spot the economy has clearly entered early this summer. Growth is holding up, the job market remains resilient and, importantly, inflation is steadily cooling. These are the ingredients for the long sought-after soft landing, although the Fed believes the mix needs to marinate a little longer to complete the recipe. That said, the policy chefs are standing at the ready, poised to douse some of the interest-rate flames that threaten to overcook the meal.

At its upcoming meeting on September 17-18, the question is not whether the Federal Reserve will lower interest rates, but by how much. The surprisingly weak jobs report for July released earlier this month, stoked recession fears and heightened the odds that the rate cut would be larger than the usual quarter-percentage point, with the financial markets pricing in a better than 50-50 chance it would be a half-point reduction. That sentiment gained traction from a subsequent weekly report featuring a big jump in initial claims for unemployment insurance, punctuating a steady, if erratic, climb already underway.

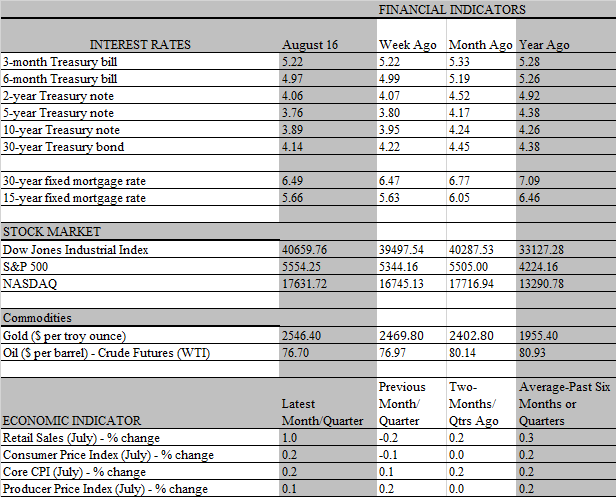

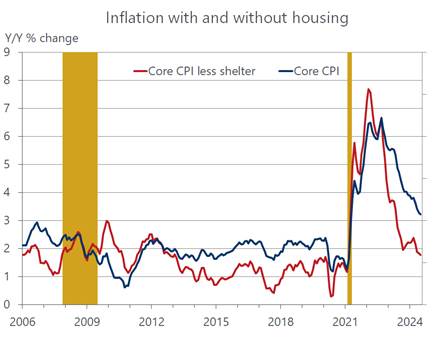

But the latest batch of data has calmed recession jitters; with a month to go before the FOMC gathers, traders now think it is a coin flip as to whether a quarter or a half-point cut is on the way. We are still in the quarter-point camp, but like the evolving consensus view, have become more convinced the Fed will pull the rate-cutting trigger in mid-September. The door to a cut opened wider this week with the July CPI data that provided solid evidence the disinflation trend is alive and well and moving sustainably towards the Fed’s 2 percent target. For the first time since March 2021, the annual increase in the overall consumer price index fell below 3 percent in July, slipping to 2.9 percent from 3.0 percent in June, after notching a muted 0.2 percent increase during the month (rounded up from 0.154 percent).

To be sure, the monthly data can be noisy, shoved around by volatile price movements on certain items, such as gasoline and food. But even smoothing out the headline data, the trend is undeniable. Over the past there months, the overall CPI has increased by an annual rate of 0.4 percent, the weakest increase over a three-month span since the tail-end of the pandemic recession in the summer of 2020. No one expects such a quiescent trend to continue, but it’s notable that over the past twelve months, fully 60 percent of all basic items in the consumer price index have increased by less than 2 percent over the past twelve months. That’s the most subdued broadly-based inflation reading since the prepandemic period.

No doubt, measures that strip out volatile price items give a better sense of inflation trends. The Fed’s preferred measure is the core personal consumption deflator, which will become available for July later this month. The next best thing that economists monitor is the core CPI, which comes out earlier and strips out food and energy items from the consumer price index. This reading reveals a less pronounced retreat in inflation than the overall index, but the trend here is also palpable and clearly welcomed by the Fed. The core index increased by the same 0.2 percent from June to July as the overall CPI; but unlike the latter, the year-over-year increase remained just above 3 percent, having slipped to 3.2 percent from 3.3 percent in June. Still, that’s the smallest increase since April 2021 and less than half the peak 6.6 percent rate hit in September 2022.

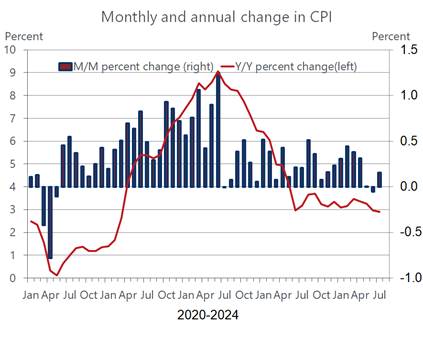

Importantly, the core CPI’s lagged retreat is entirely due to the sticky prices of services. Goods prices continue to deflate, nudged on by China’s glut of industrial commodities flooding the global market, while prices of services perked up in July. Core service prices increased by 0.3 percent, fully offsetting the drop in core goods prices during the month. The main culprit behind the stubborn stickiness of service prices lies with housing inflation. Shelter costs, including rents on primary residences, lodging away from home and imputed rent increases on owner-occupied homes, increased 0.4 percent in July, rebounding to the monthly pace seen from February through May following an encouraging slowdown to 0.2 percent in June. While the CPI measure of shelter costs overstates housing inflation, as it fails to capture the slowing trend in current market rents, its huge impact on price trends over the past year is unmistakable, accounting for over 70 percent of the increase in the core CPI. Take out housing, and core inflation is running below the Fed’s 2 percent target, coming in at 1.8 percent over the past twelve months.

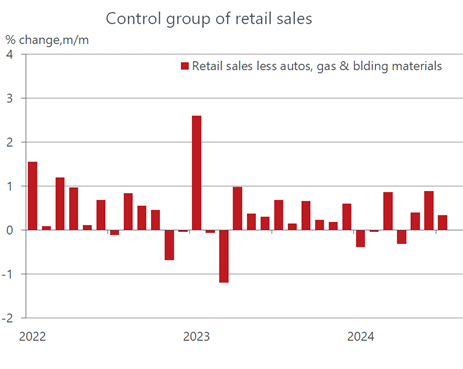

The sustained retreat in non-housing inflation opens the door for the Fed to start cutting rates in September. As noted, we believe a quarter-point cut is likely. But had the CPI turned in a weaker reading, exhibiting more deflationary tendencies on the goods side, recession fears might well have escalated, reflecting deepening concerns that demand is drying up. That, in turn, would have put more pressure on the Fed to up the ante on rate cuts, making a more compelling case for a half-point reduction. However far from drying up, this week’s report on retail sales strongly suggests that consumers retain considerable firepower, as spending in July jumped by 1 percent, far exceeding the expected gain of 0.3 percent.

True, the headline increase received a major boost from auto sales, which rebounded from the harsh June setback caused by a cyberattack on dealerships. But excluding autos, most retailers reported robust sales, with only the miscellaneous category showing notable weakness. Sales of electronics, furniture, food and beverages and general merchandise all showed solid gains. Importantly, the control group of sales that feeds into consumer spending in the GDP accounts staged a sturdy 0.3 percent gain building on the torrid 0.9 percent surge in June. With inflation receding, households are benefiting from growth in real disposable incomes that should sustain spending as long as the job market keeps on churning out more paychecks.

The good news is that initial claims for jobless benefits have declined over the past two weeks, erasing the spike over the last week of July that fanned recessionary fears stoked by the ominous rise in the unemployment rate in the July employment report. The reversal of the spike in jobless claims confirms that layoffs are not driving the increase in the unemployment rate. Instead, labor supply is growing faster than the demand for workers, but employers are still hiring, albeit less aggressively, and holding on to staff. The sustained cooling of inflation allows the Fed to focus more on sustaining job growth and keeping its quest for a soft landing alive, pointing to successive rate cuts in coming months.