The aftershocks of Trump’s onslaught of tariff announcements are still reverberating through the financial markets, adding another layer of uncertainty that has buffeted households and businesses for months. At the end of trading on Friday, investor stock portfolios absorbed a collective hit of about $7 trillion since the bombshell Rose Garden theatrics took center stage. The math is admittedly back of the envelope, based on the Federal Reserves estimate of the total value of publicly held U.S. stocks, which stood at $70.3 trillion at the end of 2024 and we estimate declined to about $66 trillion on the day of the aggressive tariff announcements. The more than 10 percent plunge on Thursday and Friday translates into about a $7 trillion haircut to investor stock portfolios, give a take a few billion.

To paraphrase, Everett Dirksen, the venerable Senator of yore, a trillion here, a trillion there, and pretty soon it adds up to real money. True, the people getting hit the most are upper middle-and higher income Americans who enjoyed huge wealth gains in recent years, thanks to the strong appreciation in stock prices. But the gains amid cooling wage growth contributed meaningfully to consumption last year, as beefed-up portfolios encouraged households to live with a lower savings rate than otherwise. A sustained wealth destruction would have the opposite effect, posing a meaningful drag on consumption and, in turn, on overall economic activity. To be sure, a two-day rout in stock prices, however painful, is too short a period to qualify as a sustained erosion in wealth so it is premature to make judgements on its real-world impact.

But while the wealth effect may still be waiting offstage, the shock effect from the barrage of announced and proposed tariffs is front and center. Indeed, the anticipation of what they might mean for the pocketbooks of households has been building for months, and some effects on behavior are already evident. Big-ticket purchases, most notably autos, have been pulled forward and businesses have been stockpiling inventories in advance to avoid supply bottlenecks as well as to beat higher prices. What’s more, given the global ramifications of the unfolding trade war, it’s worth noting that foreigners hold an ever-larger share of U.S. stocks and, hence, are not immune to the negative wealth effects. As of the fourth quarter, foreign holdings accounted for a record 18 percent of all U.S. stocks, up from 7 percent in 1990. To the extent that the wealth destruction of overseas investors curtails purchases of U.S. products it would impair the very rebalancing of trade flows that President Trump is trying to accomplish.

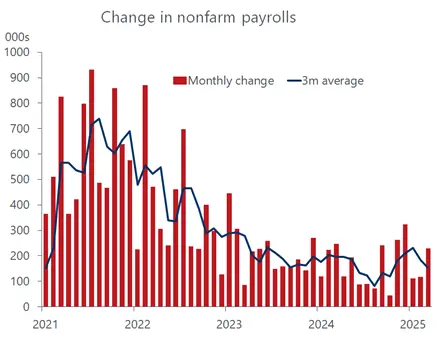

The media blitz covering the tariff bruhaha is swamping incoming data on the U.S. economy, including the key monthly employment report that would otherwise garner most of the headlines on Friday. Unsurprisingly, the report did little to short-circuit the downbeat mood on Wall Street despite the much stronger data on the jobs front than expected. Instead of the 140 thousand increase expected by the consensus for March, the economy generated a muscular 228 thousand increase in nonfarm jobs during the month. The overshoot more than offset the 48 thousand downward revisions in payrolls over the previous two months, yielding a solid average monthly increase of 152 thousand during the first quarter, only a tad softer than the 161 average for all of 2024. But it would be a mistake to conclude that the labor market ended the period with good deal of forward momentum.

For one, the Labor Department conducted its data-gathering surveys during the week spanning the 12th of the month, which is well before Liberation Day on April 2. Not only is the report backward looking, but its contents reflect employer perceptions that prevailed amid spiraling policy uncertainty. Almost to the day of the tariff announcements this week, the ill he or won’t he speculation dominated the headlines. Under such a cloud of uncertainty, it is not surprising that employers would be struck with a severe case of inertia, waiting to see what substance would emerge from the tariff threats. The details have now been revealed, but it’s unlikely that uncertainty has been dampened as we await the retaliatory measures from our trading partners. The opening salvo appeared on Friday morning with China striking back by slapping 34 percent tariffs on the U.S.

Unsurprisingly, the China rebuttal intensified the sense of anxiety in the financial markets, sending stock prices even deeper into negative territory. Also unsurprisingly, the kerfuffle sucked the Federal Reserve into the fray, with President Trump calling for immediate rate cuts just as Chair Powell in a conference with journalists was hinting at the opposite, noting that the barrage of tariffs ups the odds of higher inflation. If there is a Fed put in the offing, it will take more hard evidence of economic pain than is now evident for the Fed to act. Still, it would not be the first time that policymakers have followed the lead of the markets, and if the swoon in the bond sector continues much further, the Fed could react. The 10-year Treasury yield broke under 4 percent on Friday for the first time since last October echoing a similar downward move in the policy-sensitive 2-year yield. Both steadied and moved up later in the day following Powell’s expressed resistance to a rate cut.

It remains to be seen if the dramatic plunge in consumer and business confidence along with escalating turmoil in the financial markets will sink the $30 trillion economic juggernaut that is the U.S. economy. Like most others, we too acknowledge that the recession odds have increased due to the disruptive effects of the unfolding trade war. But as the admittedly backward-looking hard data reveal, there is still a formidable amount of firepower driving the growth engine. Indeed, there is very little in the key jobs report to suggest the economy is about to keel over. The unemployment rate did inch up, from 4.1 percent to 4.2 percent. But the rise occurred for the right reasons: the labor force grew faster than employment, resulting in a slight increase in the number of unemployed workers seeking jobs. The increase in the overall labor force participation rate is more a sign of strength than weakness in the job market. While the participation rate did slip for prime age workers, that could reflect the curtailment of immigrants, as this cohort falls mostly into the prime age group.

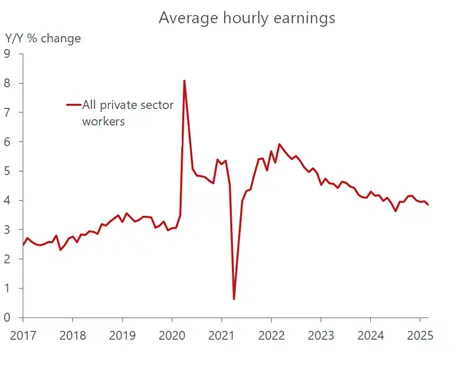

Importantly, the sturdy increase in payrolls last month also generated more purchasing power for workers. Average hourly earnings increased 0.3 percent, equaling the average gain over the previous four months. That is a slight cooling from the pace seen over the first six months of 2024, so the year-over-year increase slipped to 3.8 percent from 4.0 percent in February. But the annual increase is still outpacing inflation, providing workers with more purchasing power to sustain consumption. It also gives the Fed flexibility to stand pat while the crosscurrents buffeting growth and inflation play out and a clearer picture of the balance of risks it faces comes into focus. The betting odds of a recession this year has just risen to over 50 percent, according to Poly market, the widely watched prediction market, and traders are pricing in at least four rate cuts this year, twice as many as the Fed planned at its last meeting. At this juncture, we don’t see the hard data lining up with bleak outlook signaled by the soft data; but forecasting amid such fast-moving and tumultuous events requires a nimble response to rapidly changing facts.