The higher for longer narrative received more confirmation this week as key economic reports signaled an economy that continues to chug along and an inflation rate that stubbornly remains well above the Fed’s 2 percent target. Yet, the news could have been worse. At first blush, the headline GDP suggested that the economy’s growth engine downshifted in the first quarter even as inflation accelerated, a combination that evoked visions of nascent stagflation. A closer look under the GDP hood, however, revealed more underlying strength than suggested by the slowdown in headline growth. Importantly, a monthly breakdown of the quarterly roundup, released a day after the GDP report, indicated that inflation, while still stubbornly elevated, was at least not getting worse.

Thanks to the latter observation, the financial markets heaved a sigh of relief on Friday, as stock prices recovered all of Thursday’s knee-jerk downturn, and then some, and bond yields came off the boil. The Federal Reserve is not likely to view this week’s data as any reason to shift its policy strategy. The turn towards a more hawkish stance has evolved over the past several weeks as a procession of Fed officials acknowledged that conditions were not as conducive to a rate cut as thought a few months ago. While the bias is still for a cut at some point later this year, the upside surprises on the inflation front over the last few months have pushed back the launching date. And with the economy still riding a good deal of momentum, fears that retaining elevated rates were pushing the economy to the brink of a recession has faded into the background.

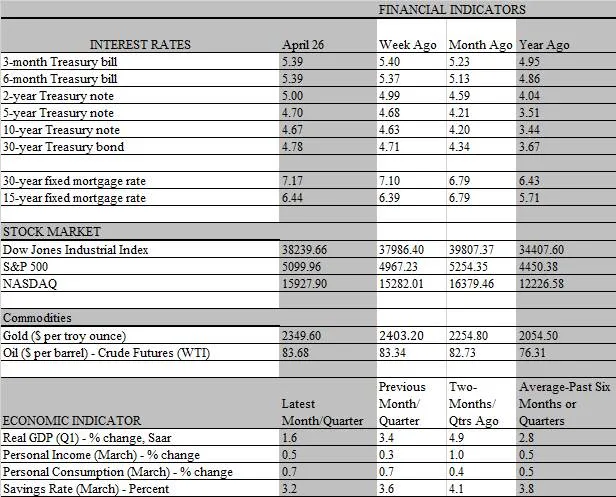

The latest batch of data supports that assessment and, importantly, dispatches unfounded concerns that the economy may be flirting with stagflation, i.e., below-trend growth accompanied by accelerating inflation. That notion emerged on Thursday when the GDP report revealed a marked slowdown in the economy’s overall growth rate to a weaker-than-expected 1.6 percent from 3.4 percent in the previous quarter and an average growth rate of 4.1 percent over the second half of last year. While the 1.6 percent reading was the weakest since the second quarter of 2022 the more concerning feature of the GDP report was that the slowdown on the real side of the ledger occurred alongside a pick-up in inflation. The big scare was the increase in the core personal consumption deflator (PCE), the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, which leaped to an annual rate of 3.7 percent in the first quarter from 2.0 percent in the previous quarter. That leap is what raised hackles in the financial markets, sending stock prices skidding and the 10-year Treasury yield up to a six-month high of 4.73 percent on Thursday.

But as the saying goes, the devil is in the details. A look under the hood shows that the economy did not stumble quite as badly as the headline GDP slowdown suggest. The setback mainly reflects the drag from surging imports and less inventory spending, both of which are highly volatile. Stripped of those components uncovers a good deal of underlying strength. Real final sales to domestic purchasers increased 2.8 percent, softer than the previous quarter’s 3.5 percent, but stronger than the 2.4 percent average over the 10 years prior to the pandemic. Take out the government and demand looks even firmer, as sales to domestic private customers increased 3.1 percent, just a tad below the previous quarter’s 3.3 percent. Consumer spending, the main growth driver, did pull back to a 2.5 percent increase from 3.3 percent, but that’s virtually spot on with the 2.4 percent, 10-year prepandemic average. Meanwhile, the import surge, while subtracting from GDP, is actually a sign of strength in domestic demand but for purchases from overseas rather than from domestic sellers.

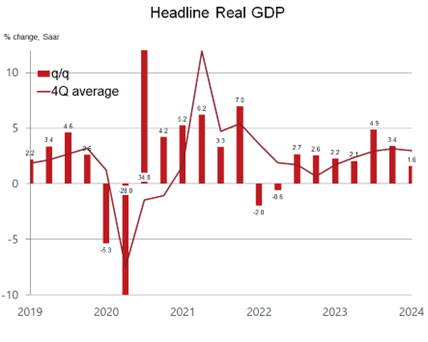

Importantly, the pullback in in personal consumption would be worrying if it reflected a declining trend throughout the quarter, suggesting consumers are running out of fuel and poised to close their wallets in the second quarter. However, the monthly income and spending report released on Friday shows that just the opposite is the case. After limping into the year with a meek 0.1 percent increase in January, personal consumption jumped by an outsized 0.8 percent in each of the following two months, the strongest monthly readings since January 2023. Only part of the increase was due to higher prices, as real consumption notched a solid 0.5 percent increase, which also matched the strongest monthly gain in over a year. The only cautionary note is that spending increased faster than disposable income, forcing households to dip into savings, lowering the savings rate to 3.2 percent. That’s the lowest rate since October 2022, and well below the 5.2 percent reached in May of last year.

However, households may feel better equipped to live with a lower savings rate, thanks to the substantial appreciation in home prices and stock values that greatly bolstered their net worth over the past year. But those gains, particularly in stock portfolios, have mainly benefited upper income individuals, whereas those down the income ladder are likely to have depleted the savings cushion built up during and immediately after the pandemic, fed by copious government transfer payments. For them, spending will rely more heavily on income growth. The good news is that wages and salaries rose by a sturdy 0.7 percent for the second consecutive month in March, the strongest since January 2023. And unlike the skewed distribution of wealth gains, lower income workers are matching, if not exceeding, the pay increases obtained by higher wage earners.

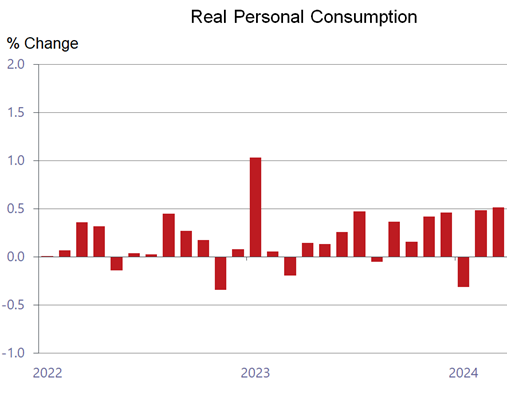

Simply put, there is no sign that consumers are running out of fuel as long as the job market continues to generate healthy paychecks, which are not eaten up by inflation. However, the jump in the core PCE deflator during the first quarter, not only threatens to rob workers of all pay gains, but it also increases the odds the Fed will keep interest rates elevated for longer, threatening to rob workers of their jobs. The quarterly jump in the inflation rate sent shock waves through the financial markets in part because it was unclear if inflation was getting hotter during the period. But like the consumer spending trend, the quarterly inflation rate looks less ominous when the monthly pattern is tracked. In a mirror image of spending, which started the year limping in, the PCE deflator came in like a lion, roaring ahead by 0.5 percent. That was more than double the 0.2 percent increase notched the previous month and matched the strongest monthly advance since June 2022.

As it turns out, that was the peak increase for the quarter, as the PCE deflator slowed to 0.3 percent in February and March. Hence, the weakness in growth and strength in inflation contained in the first-quarter’s GDP report were both front-loaded. As the period drew to a close, growth picked up and inflation eased, leaving stagflation fears in the dust and stoking a major rally in the financial markets on Friday. While that takes the sting out of the inflation scare, the Fed is likely to stay on the sidelines until at least the fall before cutting rates. Inflation may have ended the quarter on a tamer note, but the stickier components show little sign of improvement. The Fed is closely monitoring the so-called super core inflation rate, core service prices excluding housing, and its trend is anything but encouraging, increasing at an annual rate of 5.5 percent over the last three months.