The notable baseball philosopher, Yogi Berra, purportedly said that’s making predictions is hard “especially about the future”. Federal Reserve officials, as well as investors, are learning that lesson the hard way. This week alone, a procession of policymakers admitted that they made a mistake about their inflation predictions, acknowledging more forcefully again that price increases are not slowing as quickly as expected a few months ago and, consequently, they probably won’t lower rates as early as planned. Investors are equally humbled by misplaced expectations of an even steeper round of rate cuts than the Fed had forecast last December and reaffirmed at the March policy meeting.

These mea culpas have wreaked havoc in the financial markets. Stock prices have plummeted in recent weeks and market yields have soared. The bellwether 10-year Treasury yield leaped by about half-percentage point to 4.70 percent by mid-week, which, except for a few days last October, is the highest since late 2007, setting the stage for the financial crisis. Escalating Middle East tensions buffeted the markets over the last two days of the week, but prices of stocks and bonds ended the period significantly lower than they were prior to the hawkish comments by Fed officials. With the broader economy and inflation consistently running hotter than expected, it’s highly likely that the data-dependent Fed will keep rates higher for longer. The prospect of a June rate cut has been taken off the boards, as the markets are currently pricing for the first rate cut to occur in November.

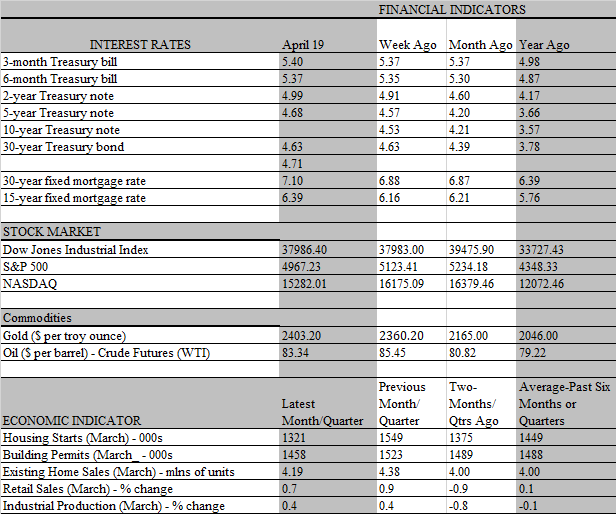

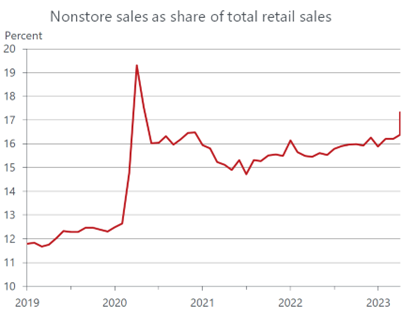

This week’s key economic indicator, retail sales, provided more evidence that the economy’s growth engine is still in high gear. Consumers, the main growth driver, continue to keep their wallets wide open, boosting spending at retailers by 0.7 percent in March, nearly double the consensus forecast. True, some extenuating circumstances contributed to the outsized increase. The Easter holiday fell earlier than usual this year, pulling some sales forward from April, spiking gasoline prices boosted sales at service stations and Amazon held a special prime-day sales event that stoked an eye-opening 2.7 percent surge in nonstore sales. Except for the height of the Covid lockdown in the spring of 2020, households are doing more of their shopping online than ever before. Nonstore sales accounted for 17.3 percent of total retail sales in March, almost 50 percent higher than the prepandemic share.

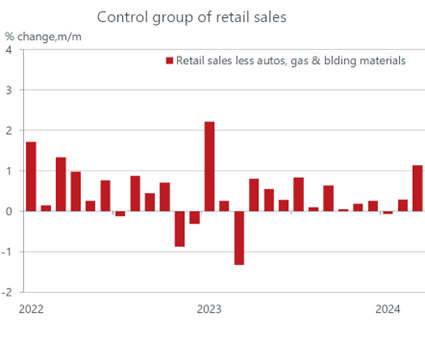

While the retail sales surge last month may overstate the strength in consumer spending, sales for the previous two months were also revised higher. Recall that the initial estimates for January and February indicated that consumers stumbled into the near year, pointing to sagging growth that would encourage the Fed to start cutting interest rates sooner rather than later. But the revised data now show that consumer spending had considerably more momentum heading into the spring, punctuated by the upside surprise in retail sales for March. Importantly, stripping out the more volatile components of retail sales ” gasoline, autos, building materials and food purchases” reveals a highly muscular trend, as this control group of sales increased by a sturdy 1.1 percent in March, the strongest monthly gain since January 2023.

That significantly outpaced the inflation rate last month, indicating another strong increase in real purchases. And since the control group of sales feeds into the GDP calculation of consumer goods purchases, the economy’s growth rate for the first quarter is likely to come in stronger than expected as well. Granted, the retail sales report mainly includes purchases of goods whereas spending on services accounts for the lion’s share of personal consumption. The more comprehensive report on personal consumption that includes services will be released next Friday. It’s unlikely, however, that there was much, if any, pullback in spending on services last month. The one category in the retail sales report that covers services “spending at restaurants and bars” notched a decent 0.4 percent increase in March.

Looking ahead, there are impulses that will give a boost to spending in April as well, which would impart some momentum at the start of the second quarter. For one, after a slow start in January and February, tax refunds are piling up in household bank accounts. As of early April, the IRS refunded about $200 billion to individual taxpayers, with the average refund $3,011, up 4.6% from a year ago. Historically, people spend those funds quickly, boosting sales at department and general merchandise stores There is no reason to believe that won’t be the case this time. For another, April also saw a special event “the total eclipse” which, like major holidays, stimulates household purchases. According to AirDna over half of U.S. cities along the eclipse’s path were fully booked for the night of April 7th, the day of the event.

To be sure, it would be a mistake to conclude that consumers will maintain spending at the current torrid pace for the rest of the year. That would mean the Fed’s rapid rate hikes in 2022 and 2023 were having no effect, removing any possibility of a rate cut. In fact, such a scenario would imply the opposite, the prospect of the Fed resuming its rate-hiking campaign. One Fed official this week even commented that a rate increase should not be dismissed out of hand if upside surprises on the growth and inflation fronts continue to appear in coming months. Given how economists and policymakers have missed the mark so far this year, nothing should be ruled out. However, while the recession fears linked to elevated interest rates that widely prevailed late last year now appear overblown, the economy is not off to the races. The door is still wide open for the Fed to start easing up on the brakes later this year.

Granted, inflation remains far enough above the Fed’s 2 percent target to short-circuit a near-term relaxation of policy. But price increases are slowing, and we expect that before the end of the year the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge ” the core personal consumption deflator ” will have retreated to 2.5 percent from the current 2.8 percent. That’s still too high, but it represents enough progress to allow the Fed to launch its rate cuts, particularly if the economy shows tangible signs of cooling. Despite the hot start to the year, we do believe that a downshifting in growth is poised to get underway and underpin the Fed’s wish for a sustained easing of inflationary pressures.

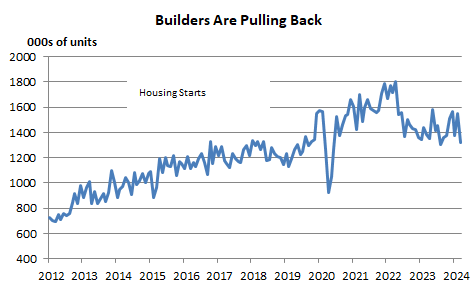

Keep in mind that while vibrant consumers continue to drive the growth engine, not all is coming up roses for the economy. Households have been able to withstand the Fed’s rate hikes for a variety of reasons, including a sizeable savings cushion, sturdy job growth and manageable debt-servicing charges due the low borrowing rates locked in before the Fed’s rate hiking campaign got underway in 2022. But those hikes are taking a toll on new borrowers, shutting many out of the housing market, those with short-term loans that need to be refinanced at the current high rate levels, and people with low credit scores that are being shunned by lenders adopting more stringent lending standards. Delinquencies are rising on subprime loans, particularly on autos and credit cards, reflecting mounting struggles of low-income households. And, not surprisingly, with mortgage rates topping 7 percent again, the housing market is taking a hit. Builders are sensing that housing affordability is getting out of reach for a broadening swath of potential homebuyers and are pulling in the reins, as signaled by the sharp drop in housing starts in March.