The inflation dragon reared its head again, unsettling the financial markets and upending expectations of when, or even if, the Fed will lower interest rates this year. Clearly, Fed officials were not happy with the March consumer price report released on Wednesday, which came in hotter than expected for the third month in a row and may well have tipped the scales in favor of fewer rate cuts than the three projected at the March 20 FOMC meeting. Even before the CPI print, several policymakers were sounding a more hawkish tone, reacting to earlier reports depicting a steamier job market than expected. Unlike the second half of last year, sturdy job growth so far this year is not occurring alongside receding inflation.

No doubt, the odds that the Fed will keep rates higher for longer have increased. With the economy retaining momentum and the labor market still chugging along, there is little urgency to pull the rate-cutting trigger. Even accounting for the long and variable lags before the full impact of the rapid rate hikes in 2022 and 2023 are felt, the economy seems to have enough cushion of strength to withstand the current level of rates for a while longer. But while traders have pushed back the likely timing of the first reduction, it would be premature to take June as the starting date off the table.

True, the noisy narrative that threw the January/February inflation data into question has been diluted by another month of stronger than expected price gains. Three months are usually enough to smooth out the noise and reveal a trend. But for a trend to be sustained it needs corroboration from ancillary data, and that source of support pointing to stubbornly high inflation is lacking. Indeed, other price-related data suggest that the disinflation trend will resume over the second half of the year, reminiscent of the second half of 2023.

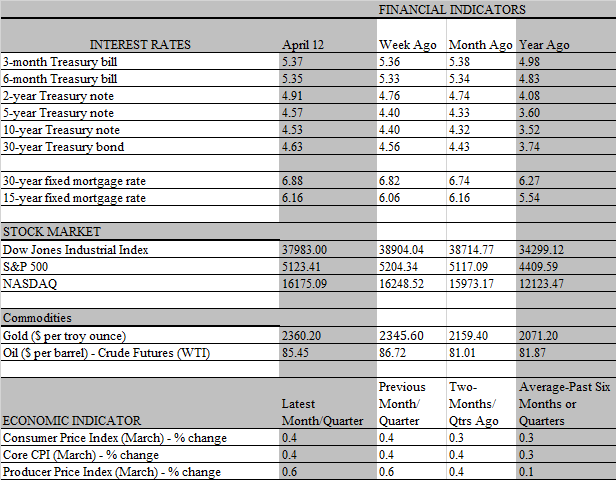

Still, Fed policy is guided by incoming data and the headline reading in the consumer price report stirred the inflation pot; it also generated enough anxiety to drive market yields sharply higher and stock prices sharply lower in the days following its release. Traders and investors do not like surprises, particularly when they conflict with positive expectations. The consensus forecast did not expect the CPI report to erase the upside surprise contained in the January and February data. But it did expect a relatively benign reading, one that at least suggested things were not getting worse. Unfortunately, the consensus was once again disappointed as both the headline and some critical details in the CPI report turned hotter. Overall consumer prices increased 3.5 percent from a year ago, up from 3.2 percent in February and the fastest increase in six months. Excluding volatile food and energy prices, the core CPI increased by the same 3.8 percent as the previous month, but expectations were for it to edge lower to 3.7 percent. The reason is didn�t is because the core index notched the same 0.4 percent monthly increase as the previous two months. That’s the strongest and longest stretch of consecutive monthly increases in over a year.

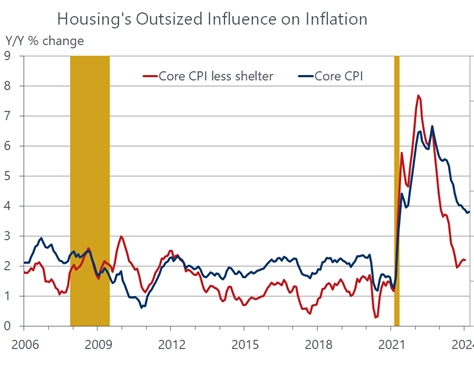

To be sure, some of the usual suspects inflamed the overall consumer price index last month. In a note accompanying the release, the Labor Department pointed out that “The index for shelter rose in March, as did the index for gasoline. Combined, these two indexes contributed over half of the monthly increase in the index for all items.” But as noted, the core CPI, which strips out volatile gas and food prices, provided no solace for inflation worriers last month. The sustained vigor in shelter prices is of particular concern as it has a one-third weighting in the overall CPI and an even larger 40 percent weight in the core CPI. If not for shelter prices, the core cpi would have increased by 2.4 percent over the past year instead of the more worrisome – and stickier – 3.8 percent.

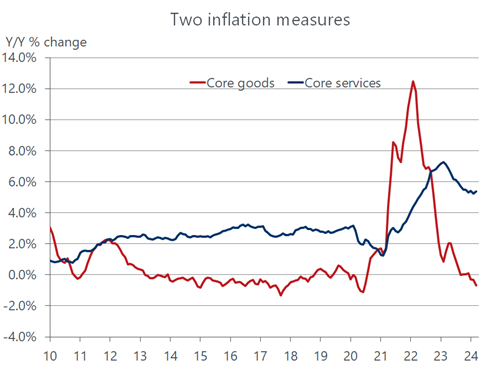

The good news is that the shelter component is poised to ease later this year when the weaker increases in market rents now underway filters through into the official measure. The bad news is that even stripping out shelter, the core CPI is ticking up as the 2.4 percent increase over the past year is visibly higher than the 1.9 percent reached last September. The culprit here is service prices that are closely monitored by the Fed and are heavily influenced by labor costs, particularly those grouped into what it known as the super-core index. In March, the super-core index increased by an outsized 0.7 percent, punctuating a string of increases averaging 8.2 percent at an annual rate over the last three months. That�s a pace not seen since June 2022, and represents an impossible hurdle to overcome for inflation to retreat anywhere close to the Fed’s 2 percent target.

As much as anything, the resilience of service prices makes the “last mile” on on the road to 2 percent as difficult to navigate as advertised. But while it is no longer a sprint like in 2023, we doubt that the remaining journey will turn into a marathon. It’s important to remember that the Fed�s preferred inflation yardstick is the broader personal consumption deflator, which is running about 1 percentage point under the consumer price index. There is a good chance that the deflator, particularly the core PCE, will provide a better reading for March when it is released later this month than the consumer price index. For one, the housing component has a smaller influence on the deflator. For another, the producer price index for March that was also released this week came in weaker than expected, as did the components that feed into the PCE deflator. The core PCE deflator increased 2.8 percent in February from a year ago, and we estimate that it slipped to 2.7 percent in March. That’s still too high for the Fed’s comfort, but not as alarming as the recent CPI trend.

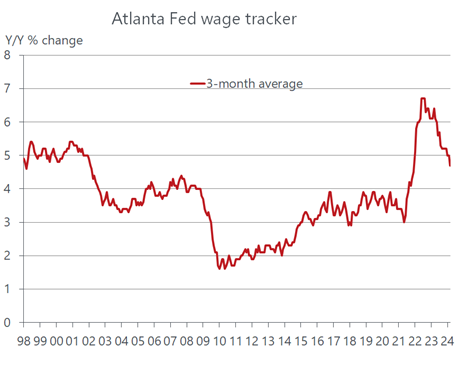

Moreover, the critical influence behind service prices, wages, is flashing positive signs. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s wage tracker fell from 5.0 percent to 4.7 percent in March, the lowest annual increase since December 2021. Importantly, small businesses, where wages are by far the biggest expense item, are turning less aggressive to retain workers. According to the March survey by the National Federation of Independent Businesses, just 21 percent of firms are planning to raise wages over the next three months, down from 30 percent last November. We suspect that easing wage pressures will continue over coming months as the job market softens, worker bargaining position weakens, and employers redouble efforts to protect margins from rising costs.

The process will take time to play out, which heightens the odds that the Fed will stay on the sidelines for a while longer than thought a few months ago. That may cause further consternation among investors, but a continuation of tighter financial conditions currently unfolding may serve the Fed’s purpose by curbing demand and taking steam out of the economy’s growth engine, something that aids in the inflation-fighting effort. The risk, of course, is that conditions could deteriorate too quickly, and the Fed falls behind the recession curve. It is not unusual for the economy to appear as vigorous as it is now for a quarter or two before a downturn sets in.