The post-election tremors in the financial markets are gradually subsiding, as the calendar moves further away from November 5 and acceptance sets in. that said, policy uncertainty remains an albatross overhanging the markets, and some key cabinet positions, most notably the Treasury Department head, have yet to be filled. Hence, the full measure of President-elect Trumps position on tariffs, taxes and deregulation has yet to be fleshed out. The sudden, but not entirely unexpected, departure of Trumps nomination as head of the DOJ due to widespread opposition to his candidacy suggests that not all the presidents bold policy proposals will be rubber stamped by Congress.

As the final weeks of the Biden Administration winds down, the incoming regime will be inheriting an economy that is still firing on most cylinders. However, a number of pitfalls looms, which could make for a bumpy ride heading into the new year. The most disruptive is the geopolitical climate, which is turning ever-more treacherous with the escalation of the war in Ukraine and a Mideast conflict that shows only faint signs of closure. So far, these external tensions have had little effect on the financial markets, which may have become dangerously complacent to events that have been ongoing for some time. There may also be a growing sense that the Trump administration will have more success in cooling things down than was the Biden administration. Time will tell if this is the case, but the threat of a severe correction in the financial markets if these conflagrations get out of hand should not be dismissed lightly.

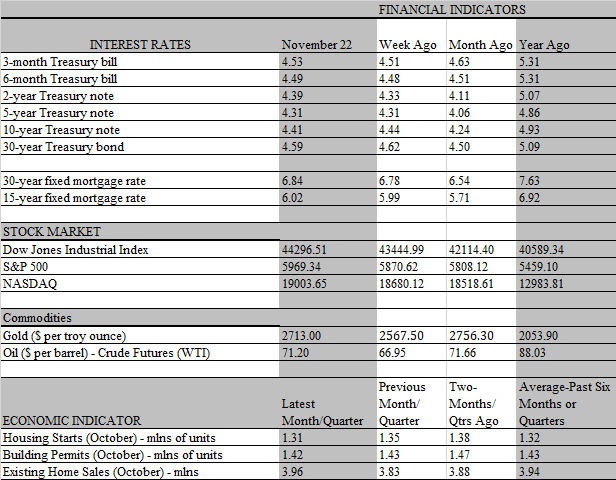

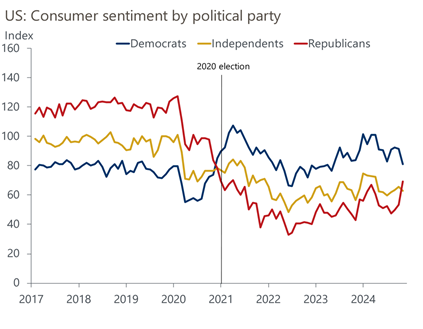

Following the Thanksgiving holiday, some key events and economic reports will hit the headlines that should provide a clearer picture of the economic landscape as well as the next move by the Federal Reserve. Keep in mind that recent data have been heavily distorted by inclement weather and strikes. Those disruptive influences should wash out in the next batch of data, which will provide the Fed with a cleaner sense of how the economy is faring. The need for less noisy hard data is becoming more apparent as the soft, or subjective, data, which many economists look to for guidance into the future has become less reliable. The reason: many of the surveys that underpin the soft data have become overly influenced by politics.

For example, consumer and business sentiment indicators are frequently used as a guide to potential spending and investment decisions by households and companies. That makes sense since the more optimistic people are about job, income, and growth prospects, the more likely are they to open their wallets and budgets for spending and investment purposes and vice versa. But in the highly polarized political climate that has evolved in recent years, the usefulness of these indicators has been greatly diminished.

A clear example of the divergent ways households with different political affiliations feel about the economy can be seen in the University of Michigan surveys of household sentiment. During the 2016-2020 Trump administrations, Republicans clearly had a much more upbeat view of the economy than Democrats. During the Biden administration, however, just the opposite perspective has emerged. Of course, during both administrations, except for the Covid-induced recession, the economy fared quite well. This week, the final survey for November was released and only weeks since the November 5 election, the mind-set of Republicans has turned sharply more upbeat, whereas just the opposite occurred for Democrat-leaning households. In November, the sentiment index for Republican households jumped by 15 points whereas for Democrats it fell by 10 points.

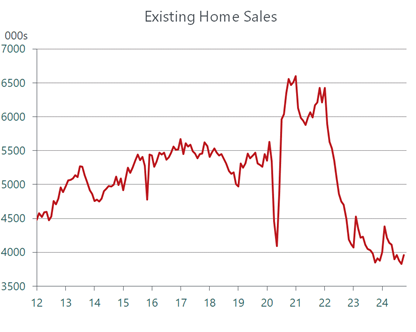

Yet, the fundamentals underpinning the economys performance have barely changed. As noted earlier, the growth engine is still powering forward, albeit admittedly in a modestly slower gear. That slowdown should not be surprising, given the lingering toll that three years of high interest rates and prices are having on budget-constrained consumers and some specific sectors of the economy. In time-honored fashion, the housing market continues to be the poster child of the damage inflicted by both influences elevated mortgage rates and spiraling home prices. That combination has damaged affordability and shoved a broad swath of households out of the market, sending sales tumbling. Thats particularly the case for existing homes as property owners are reluctant to give up the low rates on mortgages obtained years ago and are keeping their homes off the market. Hence, prospective home buyers, even those that can afford the purchase, are facing slim pickings. Many are forced into the rental market, which drives up rents and diverts builders from constructing new homes to multi-family developments, where profits are more lucrative.

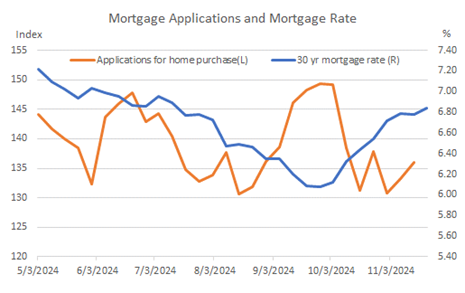

For a while, it appeared that home sales were poised to bounce off the bottom as mortgage rates fell by more than a full percentage point from the nosebleed level of over 7 percent during the spring. That decline tracked the fall in market yields, particularly on the bellwether 10-year Treasury issue, as traders anticipated steep rate cuts by the Federal Reserve in response to what appeared to be a marked weakening in economic activity and a steadily cooling inflation rate. However, following the second rate cut by the Fed, market yields have backed up sharply and so too have mortgage rates, which surged by more than three-quarters of a percent since hitting bottom in late September, and are now just a tad under 7 percent again.

That rebound will put the kibosh on a nascent recovery in home sales that occurred in October, when sales of existing homes rose by a modest 3.4 percent. Keep in mind that sales of existing homes reflect contracts signed two months earlier, when mortgage rates were much lower. Since then, mortgage applications have fallen sharply in response to the spike in mortgage rates and that will translate into weaker sales in coming months. It remains to be seen if the rebound in market interest rates continues and takes a toll not only on the housing market but the broader economy. Our sense is that the rebound is overdone, reflecting an overreaction to some fears that the prospect of higher tariffs, tax cuts and mass deportation will lead to more inflation and higher interest rates. On paper, that concern is understandable, but in reality bold campaign promises tend to get watered down before reaching fruition.