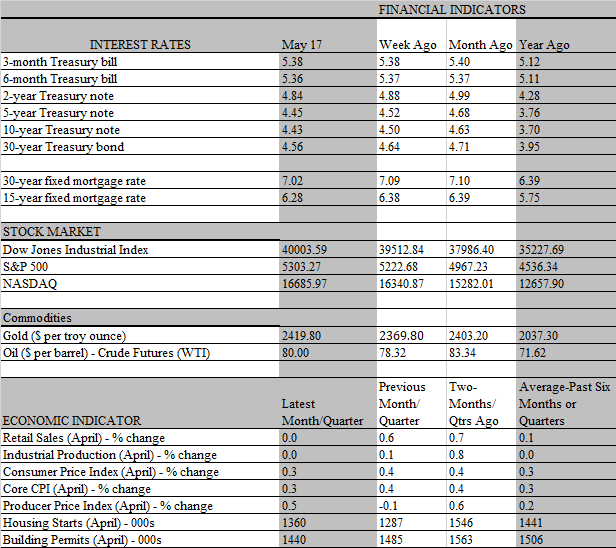

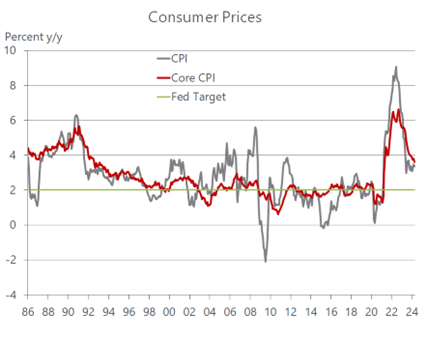

Three steps back, one step forward for disinflation. That’s clearly too much of a bumpy ride which, if sustained, would not lead to the Fed’s 2 percent destination. That said, a case can be made that an array of flukes skewed the hot inflation data over the first three months of the year whereas the tamer reading in April, revealed this week, is more reflective of underlying conditions. Whether or not that’s looking through rose-colored lenses, the Fed is not inclined to take the bait. It will take more than one-month of encouraging data to prompt Fed officials to move up the start of its rate-cutting plans. The financial markets, in contrast, are more inclined to see green shoots in the inflation battle; following this week’s encouraging consumer price report, traders now believe the worm has turned and are pricing in a cut sooner rather than later, pulling the initial cut forward to September from November. Still, an observer could get whiplash monitoring the repeated shift in market expectations as to when the rate-cutting campaign would begin.

To be sure, the market’s latest pivot towards an earlier move was not made in a vacuum. In addition to the tamer inflation readings, the latest batch of data also depicts an economy that is losing steam. It’s main growth driver, consumer spending, took a step back in April, and factories cut production. The combination of easing demand and the healing of pandemic-related supply disruptions sets the stage for a resumption of the disinflation trend that was rudely interrupted during the first three months of the year. Still, we have seen this movie before and the script needs more work before being accepted by its most important audience, the members of the Fed’s policy-setting committee. If the public comments by policymakers this week are any indication, they are giving at best, muted applause to the latest data.

For one, the week’s main inflation report, the consumer price index, is still running well above the Fed’s comfort level. The 0.3 percent increase from March to April in both the headline and core CPI was marginally softer than expected and lowered the year-over-year increase to 3.4 and 3.6 percent from 3.6 and 3.8 percent, respectively. Both measures are significantly off their peaks hit in 2022, and the core index increased at the slowest pace since April 2021. Indeed, the decline from a year ago in the core CPI was the first in six months. However, both are increasing much faster than they were prior to the pandemic and imply that the Fed’s preferred inflation measure, the personal consumption deflator that will be released later this month, remains well above the 2 percent target.

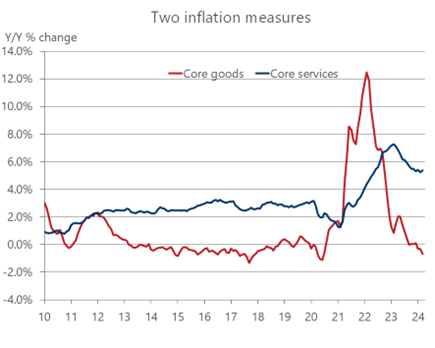

Of course, the Fed will not wait for inflation to retreat to 2 percent to start cutting rates. By then it would probably be too late to prevent the economy from descending into a recession. But it is taking longer than usual for the Fed’s rate hikes in 2022 and 2023 to bring inflation under control, and it will take several months of benign inflation reports to instill confidence that the trend towards 2 percent is firmly in place. Most of the improvement over the past year reflects the sharp slowdown in goods prices, as pandemic-fueled demand for goods has waned and supply shortages have eased. But that trend has just about run its course; if anything, goods prices have started to firm up in recent months as remote work has become more entrenched, putting a floor under demand for home-related products. Hence, further progress on the inflation front would need to come from slower increases in service prices, which is only grudgingly complying.

In fact, core service inflation has been stuck at 5.3 percent over the past five months after falling from a peak of 7.3 percent in February 2023. These prices have been buoyed by a rotating list services over the period, most recently by the cost of auto insurance and repair, medical care, and financial services. These increases have mostly peaked and are poised to slow in coming months. The rising cost of auto insurance and maintenance is a lagged response to the earlier surge in new and used car prices when parts shortages curtailed supply. That impact has mostly dissipated as inventory on dealer lots have been rebuilt to normal levels. Likewise, financial service prices are linked to the performance of financial markets, and it’s unlikely that the 25 percent spike in the S&P 500 last year will be replicated this year. Meanwhile, some of the acceleration in medical care prices reflects a one-time catch-up of wage increases associated with union activity, highlighted by the settlement with 75 thousand Kaiser Permanente strikers last October.

However, a main driver of service prices, housing costs, has been far more stubborn and has an outsize influence on consumer prices, accounting for about one-third of the overall CPI and 40 percent of the core Index. Shelter costs have increased by 0.4 percent in each of the last three months and 5 of the last six months and are up 5.5 percent from a year ago. The good news is that the trend is turning lower, as the 5.5 percent increase in April is the slowest since May 2022 and is markedly below the 8.2 percent reached in March of last year. What’s more, the rental component of housing costs does not yet capture the much smaller rent increases that are currently being signed on new leases. This trend should gradually wend its way into the housing component and contribute to slower inflation readings going forward.

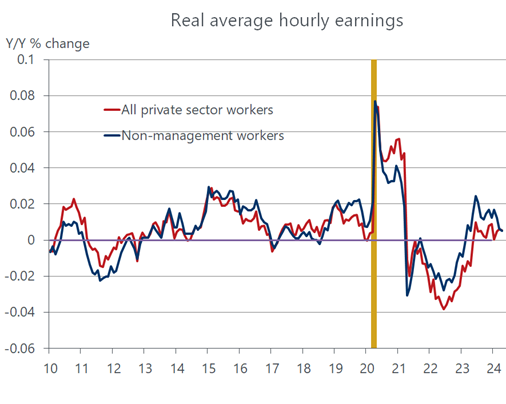

That said, the Fed has little direct influence over housing costs and is focusing on other service prices that are proving harder to wrestle under control. The so-called supercore inflation rate ” core service prices excluding housing” has increased by an outsize 6.3 percent annual rate over the past three months. Importantly, these services are highly labor intensive and, hence, their prices are more directly influenced by wage trends than is the case in other sectors of the economy. In a recent study by former Fed chief Ben Bernanke and IMF economist Oliver Blanchard, it was observed that wage trends had little to do with the surge in inflation in 2022 and 2023 but could be a major factor preventing inflation from falling further. That notion aligns with the current Fed thinking that continued progress on the inflation front will require more cooling in labor conditions.

No doubt, the job market is cooling off from the torrid pace last year that strengthened the bargaining position of workers. Job openings have declined, fewer workers are voluntarily quitting their jobs and payroll growth is slowing. Importantly, so too is wage growth, which has recently been slowing faster than inflation. With prices taking a bigger bite out of income, the risk is that the combination of sustained high interest rates and declining real wages will take the steam out of consumer spending, the economy’s main growth driver. The setback in retail sales last month reported this week may be an early sign that consumers are pulling back, although its more likely that the strong sales increase in March — stoked by an early Easter holiday and an Amazon Prime Day sales event, pulled forward sales that would otherwise have occurred in April. That said, we expect that consumers will be turning more frugal in coming months as job gains and wage growth continue to cool and low and middle-income households feel the impact of elevated interest rates more deeply. Simply put, conditions for the Fed to cut rates should be in place by September.