Like the Energizer Bunny, the US economy continues to forge ahead, expanding well beyond the expiration date that last year’s recession worriers thought would have arrived by now. Not only did a slew of incoming data this week depict more stamina in activity last month than expected, but the economy had more momentum at the end of last year than previously estimated. According to the third, and final, revision of fourth-quarter GDP, the economy grew at a 3.4 percent annual rate during the period, up from the previous tally of 3.2 percent. Stronger consumer spending accounted for much of the upward adjustment, but virtually all cylinders in the economy’s growth engine were humming towards the end of the year.

Importantly, growth on the income side of the economy’s ledger caught up with the spending side, narrowing an exceptionally wide gap that had underpinned GDP growth in recent years. In theory, income and spending should be moving at the same pace, as one person’s outlays is another’s income. However, the two sides can diverge for a period of time as the data are gathered from different sources and measurement issues create other statistical discrepancies. For the first time in five quarters, gross domestic income increased faster than gross domestic product, with the former leaping by 4.8 percent, the strongest gain since the fourth quarter of 2021.

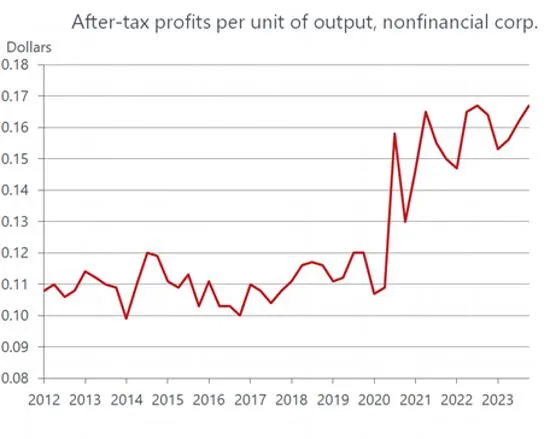

Significantly, the third revision of GDP includes corporate profits, which added considerable heft to the income side of the ledger in the fourth quarter. recording the strongest increase since the second quarter of 2022. What’s more, there were no signs of margin compression coming from rising labor costs, which were more than offset by productivity gains and price increases. Unit after-tax profits in the nonfinancial corporate sector equaled the record set in the third quarter of 2022, adding fuel to the stock market rally over the past six months. Indeed, the S&P 500 gained 10.2 percent in the first quarter of 2024, the strongest start to a year since 2019.

While the GDP report is backward looking, the economy is showing little sign of fatigue so far this year. True, consumers, the main growth driver, seemed to be cutting back, as retail sales sagged in both January and February. But Friday’s broader report on personal income and consumption revealed that households more than compensated for the setback in goods purchased at retailers by stepping up spending on services. In current dollars, personal consumption on goods and services jumped ty 0.8 percent, the strongest monthly gain in over a year. Adjusted for inflation, the increase was just as impressive. Real personal consumption rose by 0.4 percent, more than offsetting the 0.2 percent decline in January and lifting the year-over-year gain to 2.4 percent from 2.0 percent.

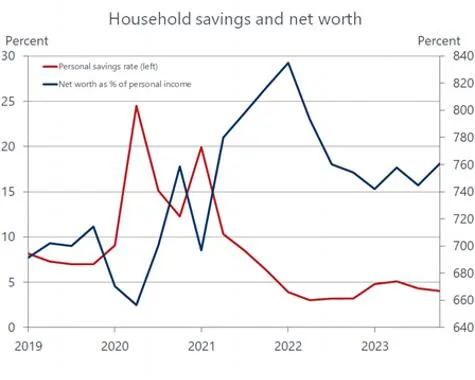

The bad news is that the income side seems to have relapsed, returning to the lagged response behind spending that prevailed over the previous two years. Personal income did increase by 0.3 percent in February, but that was more than eaten up by inflation and taxes, as real disposable income fell by 0.1 percent during the month. Hence, households relied more on savings to support spending, as the personal savings rate declined to 3.6 percent – the lowest since December 2022 – from 4.1 percent in January. Clearly, this is not a sustainable source of spending, but we are not overly concerned over a one-month outcome.

For one, the setback in income growth reflected lower receipts from dividends, which were uncommonly strong in previous months and some payback was to be expected. Wages and salaries, the biggest income component and most powerful driver of spending, advanced by a healthy 0.8 percent, the strongest gain in 18 months. As long as the job market generates sturdy increases in paychecks, households will keep their wallets and purses open. For another, the decline in the savings rate does not mean households are being drained of financial resources. If anything, just the opposite is the case as ballooning stock portfolios and rising home prices are driving up household net worth to record levels. There is a time-honored inverse correlation between household net worth and the savings rate. When people feel wealthier, they tend to save less. The 10 percent increase in stock prices in the first quarter added more than $3 trillion to the market value of directly held equities in household portfolios.

The ongoing strength in consumer spending should lead to another muscular performance for the economy in the first quarter, driving GDP growth north of 2 percent. While that would still be slower than the 3.4 percent and 4.9 percent growth rates logged in the previous two quarters, it would mark the seventh consecutive quarter of growth above 2 percent, which is considered to be the economy’s noninflationary growth rate. The question is, does the Fed need to see much slower growth to get inflation down to its 2 percent target? Or would it still cut rates, as planned, believing that inflation can continue to retreat amid supply and productivity-driven above-trend growth that prevailed last year.

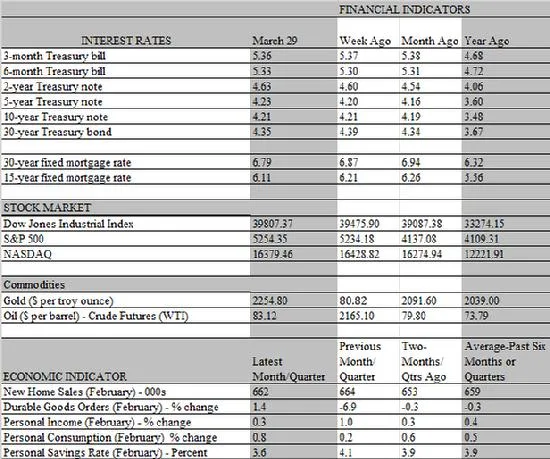

The current median forecast of Fed officials, revealed at last week’s FOMC meeting, is that three rate cuts are still in the cards for this year. However, policy makers are understandably coy about when the first rate cut will take place, reflecting the upside surprises in most incoming economic and inflation data. Fed chair Powell noted at the post-meeting press conference that he needs to see more evidence that inflation is moving sustainably towards 2 percent, and Fed Governor Waller was even more strident this week, saying that the Fed is in “no rush to cut interest rates”. The personal consumption deflators released on Friday did little to speed up that timetable. True, both the overall and core PCE deflators came in as expected in February, omitting another element of surprise on the upside. But neither moved decisively closer to the 2 percent target, increasing within the 2.5-3.0 percent range seen in recent months.

The good news is that the year-over-year increase in the core PCE deflator, which is the Fed’s preferred measure, ticked down to 2.8 percent from 2.9 percent in January, marking the slimmest increase since March 2021 and half the 5.8 percent inflation rate hit in February 2022. The bad news is that progress in recent months shows more signs of stalling out than improving. Over the past three months, the core PCE deflator increased at an annual rate of 4.5 percent; what’s more, the supercore rate – core service prices excluding housing – that the Fed is closely monitoring has also increased at an uncomfortable annual rate of 3.5 percent over the past three months. The supercore rate is linked to the trend in labor costs, which has been moderating but is still increasing at a faster pace than is consistent with the Fed’s 2 percent target. Clearly, a weaker job market would hasten the moderation in wage growth and encourage the Fed to start cutting rates sooner rather than later. The March jobs report, due next week, will no doubt affect the odds of when that first move will occur.

From our lens, the string of upside surprises combined with Fed messaging shifts the odds of the first rate cut from May to June. There is a growing sentiment in the market for a later start, but we believe that the inflation retreat will resume in coming months as there is a lot of disinflation in the pipeline and the slowdown in wage growth is poised to gain traction. The housing component of incoming inflation gauges, particularly the CPI, does not capture the slowdown in market rents that is underway and the steady decline in the voluntary quit rate among workers points to a further moderation in wages. There is still a lot of information for the Fed to digest before its June meeting, but we believe it will have enough evidence pointing to sustained lower inflation by then to pull the rate-cutting trigger.