The much-anticipated jobs report for November should not deter the Fed from cutting its benchmark rate by another quarter-point at its upcoming December 17-18 meeting. For sure, a case can be made for staying put. The economy generated a tad more jobs during the month than expected and the previous estimates of job gains for September and October were revised upward by a modest amount. A solid gain in payrolls last month was widely expected, as a big chunk of the 227 thousand increase reflected the recovery of jobs lost due to hurricanes and strikes in October. Still, even after adjusting for these temporary shocks, the job market is looking stronger than it did back in September when the Fed, in response to a weak August jobs report, slashed rates by an outsize half-point. Then, as now, job growth bounced back the following month and, as is likely again in mid-December, the Fed cut rates a second time at its subsequent meeting, albeit by a smaller quarter-point.

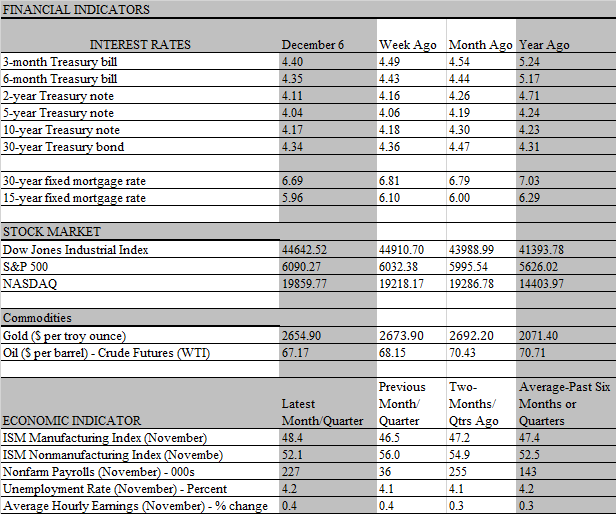

The markets had priced in a high probability of a rate cut at the December policy meeting before the jobs report, and those odds increased after the reports release of Friday morning. Unless there is a compelling reason to buck expectations, the Fed is likely to follow through so as not to stoke market volatility. Aside from the expected solid increase in payrolls last month there is little in the jobs report to justify a pause. Looking past the monthly gyrations, there is a decidedly cooling trend in job growth, as the three-month average of payroll increases has slowed to 173 thousand from 251 thousand in 2023. As recently as the first quarter of this year, the monthly gain averaged 267 thousand.

True, worker earnings staged another solid gain, rising 0.4 percent over October and 4.0 percent over the past year for the second consecutive month. Both the monthly and annual increases are stronger than the pace seen over the spring and summer months. But its doubtful that this reflects an improvement in worker bargaining power, which would send a stronger inflationary signal to the Fed. More likely is that the upward tick, particularly last month, was an anomaly linked to the timing of the payroll survey as well as some distortions caused by the composition of job changes. Note, for example, that there was a big swing in professional and business service jobs, where wages are above average, from a 23 thousand reduction in October to a 26 thousand gain in November. Meanwhile, workers in retail, where wages are below average, saw their jobs cut by 28 thousand last month, about 24 thousand more than in October.

Hence, the payroll gain in November was more heavily driven by high-wage workers, skewing the average wage higher. Even so, a 4 percent increase in wages would not be inconsistent with the Feds 2 percent inflation target, as productivity growth has accelerated over the past two years, averaging almost 2.5 percent compared to a longer-term trend of 1.5 percent. That, together with a 2 percent inflation rate could support a wage growth of 4.5 percent. And while the pickup in productivity growth may not be sustained, nor should high-wage workers continue to drive the increase in jobs. In recent months announced job cuts have been more prevalent among white-collar than blue-collar workers.

Indeed, while the survey of companies which provides the payroll count was slightly stronger than expected, the companion survey of households portrayed less favorable labor conditions. For one, the unemployment rate edged up to 4.2 percent from 4.1 percent in October. Unrounded, the rate actually stands at 4.246 percent, just a touch below the three-year high of 4.253 percent high in July. To be sure, this is still a historically low unemployment rate. However, it is up from a cycle low of 3.5 percent in July of last year and a rise of that magnitude has been a reliable portent of past recessions.

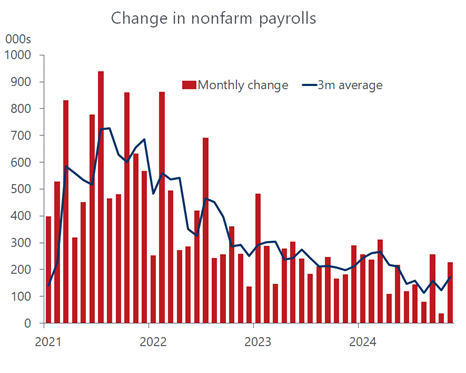

Of some concern is the rise in the number of permanent job losers, which climbed to a three-year high in November. The increase has been accompanied by a longer duration of unemployment; median weeks of unemployment rose from 10 in October to 10.5 in November, the longest since December 2021. The data on permanent job losers and the duration of unemployment are consistent with a labor market where those who have jobs are relatively secure because layoffs have not been broad-based, but those who do lose their jobs struggle to find new work as hiring has been curbed.

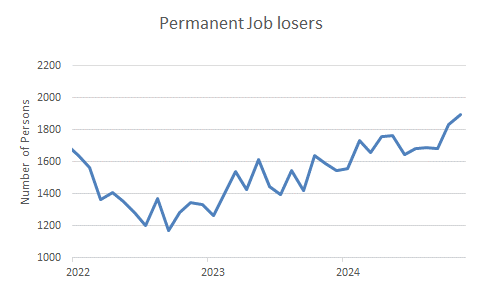

One striking trend echoing that struggle can be seen in the sharp drop in the job-finding rate i.e., the percent of unemployed workers in any given month that landed a job the following month. That rate plunged to the lowest level since the Covid recession in November. Odds are, some quirks contributed to the outsized drop, but there is little question that jobless workers are having trouble finding a new position. That is consistent with the growing trend of workers deciding to hold on to their existing jobs rather than voluntarily quit for a position elsewhere. Not only are workers less confident of securing another job, but the incentive to do so has diminished as the pay gap between job switchers and job stayers has virtually vanished.

Simply put, there is nothing in the November employment report to change our view that the Fed will lower rates by a quarter point at its December 18 meeting. The payroll data from the company survey, which the Fed probably gives more weight to, was a touch stronger than expected, but we don’t think the Fed will disregard the softness in the household data, particularly the upward drift in the number of permanent job losers.

Looking ahead to 2025, we think the Fed will take a more cautious approach to lowering rates as inflation continues its bumpy path back to 2%. We don’t expect the Fed to lower rates at the January meeting and do see a growing risk that the Fed cuts rates in 2025 fewer than the four times it projected in September. Also, President-elect Donald Trump could implement aggressive tariffs that would push up inflation, potentially giving the Fed reason to lower rates more gradually than we currently anticipate. However, the Fed isn’t going to make decisions about monetary policy based on possible changes in fiscal policy or tariffs but will wait until those policies are implemented and it can assess their impact on the labor market and inflation.