The conversation about the Federal Reserve and the economy underwent a dramatic shift on Friday with the release of the all-important monthly jobs report. Traders and investors abruptly abandoned all skepticism as to whether the Fed will lower interest rates at its September meeting, The question now is not if, but by how much, and is it too late to keep the economy out of a recession? All eyes will be on Chairman Powell’s comments scheduled to be delivered at the annual Jackson Hole symposium on August 22-24. Many now think he will send a stronger signal that the rate-cutting trigger will be pulled for the first time in 4 1/2 years at the September 18 confab, abandoning the equivocating stance he conveyed at the press conference following this week’s FOMC meeting.

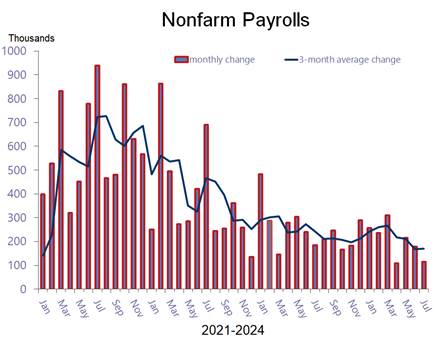

For sure, it would be premature to conclude that the economy is in dire straits, urgently in need of a resuscitating monetary boost to keep it out of recessionary waters. But the jobs report for July checked all the boxes the Fed needed to see for convincing evidence that the balance of risks facing the economy has shifted from too much inflation to too little employment. The downshift in job growth in July was as dramatic as it was surprising, even as most other details of the report portrayed more weakness than strength. The consensus expectation was that the economy generated around 175 thousand net new jobs in July and the unemployment rate would, at most, have crept up from 4.1 percent to 4.2 percent. Instead, job growth downshifted to 114 thousand from a downwardly revised 179 thousand increase in June and the jobless rate spiked from 4.1 percent to 4.3 percent, the highest since October 2021.

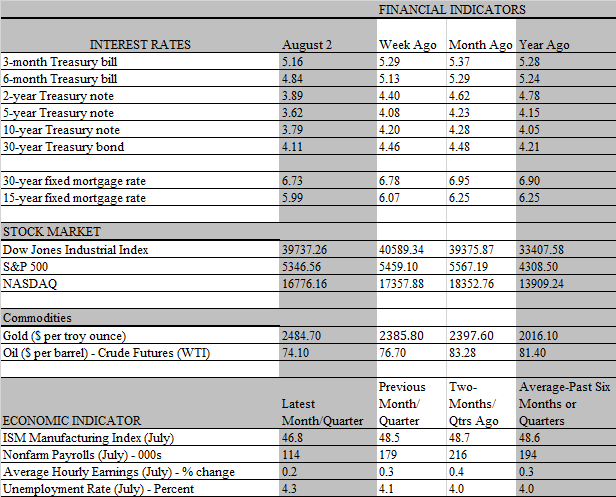

The gap between expectations and the actual data was exceptionally wide which, unsurprisingly, set off a violent reaction in the financial markets. Stocks tanked and market yields plunged, with the bellwether 10-year Treasury yield slipping below 4 percent, hitting the lowest level of the year. Indeed, the markets were already skeptical of the Fed’s indecision about cutting rates before the weak jobs report was released on Friday morning, as key reports released on Thursday provided a ominous portent of what’s in store. Weekly applications for unemployment benefits leaped to the highest level in more than a year, and an index of manufacturing activity sunk further into recession territory, with the employment subindex plunging to its lowest point since July 2020.

Perhaps the only upside surprise in the jobs report is that it did not confirm the drop in manufacturing employment, as factory jobs were virtually unchanged last month. But manufacturing only accounts for about 10 percent of all economic activity and jobs, so it is not a headline mover of conditions. On a broader scale, more than half of all private industries reduced staff, the first time the Labor Department’s diffusion index fell below 50 since the Pandemic recession. Before that, you would have to go back to the Great Recession to find another time that most industries were downsizing. Another ominous signal: the so-called Sahm Rule was triggered by the rise in the unemployment rate. This widely followed rule says that the economy is in a recession if the three-month average of the unemployment rate rises 0.5 percent or more above the prior 12-month low for that average. That threshold has now been met, as the three-month average through July equals 4.1 percent, up from a 3.6 percent average in August.

While the doom and gloom permeating the financial markets is understandable, such a knee-jerk reaction is not uncommon. Nor is it justified, in our view. True, some of the traditional markers of a recession have appeared, and a good case can be made that the Fed is falling behind in its efforts to stave off a recession. A vocal minority of commentators felt that the Fed should have cut rates at its meeting this week. Keep in mind that Fed policy works with a lag, so if the economy is already in, or on the cusp of a recession, it may be too late to rescue it. But despite triggering the Sahm rule, we do not believe the weak reports this week are enough to portray recessionary conditions.

Forget for the moment that the Fed correctly does not respond to one month of data, which can be volatile, impacted by special factors, and give a misleading read on emerging trends. For example, the Labor Department said that Hurricane Beryl did not have a discernable impact on last month’s employment. But that’s hard to believe, as the same report showed that the number of people who did not show up for work hit a record high during the month. What’s more, of the eye-opening 353 thousand increase in unemployed individuals in July, fully 249 thousand were on temporary layoffs, and it’s more than likely that at least some of that increase was related to the Hurricane. That may also have accounted for the drop in the workweek, which slipped from 34.3 to 34.2 hours.

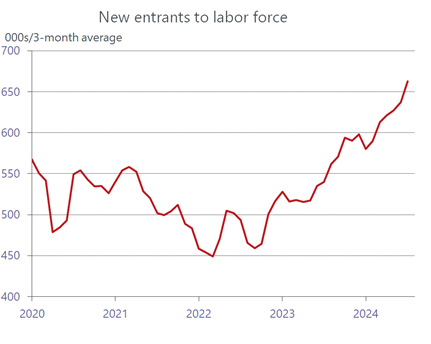

Moreover, don’t disregard the fact that more than 100 thousand jobs were created last month, which historically is a solid increase. The major reason the unemployment rate increased during the month is because the supply of workers increased faster, with the labor force increasing by 420 thousand workers, paced by a surge of new entrants to the labor market. With the job market softening from the white-hot days of 2022- 2023, many of those jobseekers did not land positions right away. While disconcerting for those looking, it would be worse if the rise in unemployment reflected large-scale layoffs by companies. That’s not happening yet. Instead, employers are cutting back hiring and laying off temporary workers.

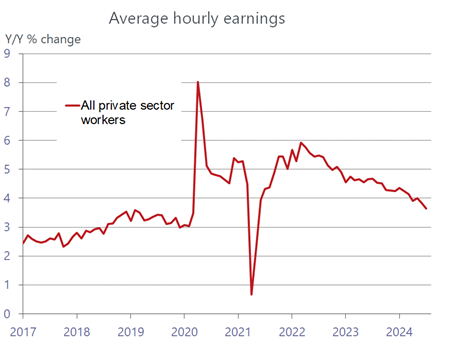

This, in fact, is the pathway to a soft landing that the Fed wants the economy to travel. The key to reining in inflation, which, until now has been the Fed’s top priority, has been to curb the rise in labor costs. Massive layoffs would, of course, do that. But it would also send the economy into a recession. The more benign path to disinflation is for the supply of workers to increase faster than demand, as more competition for jobs would translate into softer wage increases. That pattern is clearly underway, as average hourly earnings slowed to 3.6 percent over the past year from 3.8 percent in June and 4.0 percent in May. The annual increase is the slowest since the worst of the Pandemic recession in March 2020.

The Fed has persistently noted that it would like to see wage growth slow to 3.5 percent, which after accounting for normal productivity growth of 1.5 percent, would be consistent with its 2 percent inflation target. Not only has that inflection point been reached, but productivity is coming in far stronger than expected, surging by 2.3 percent in the second quarter and by 2.7 percent over the past year. To be sure, the hourly earnings data in the monthly report is not the most reliable measure of labor costs, as it is influenced by the composition of job changes from month to month. Other measures are more influential on the Fed, but the most important one, the quarterly Employment Cost Index, is also slowing considerably. The year-over-year increase in the wage and salary component of the ECI fell to 4.0 percent in the second quarter from its 5.6 percent peak in 2022.

In sum, the July employment report showed considerable softening in the labor market, but we think the data, particularly the rise in the unemployment rate, is overstating emerging weakness. Still, the Fed needs to guard against a scenario where the rise in the unemployment rate triggers a reinforcing cycle of reduced incomes and spending and more job losses. Fed Chair Powell said he didn’t want to see any “material cooling in labor market” conditions, and the July data probably rises to that standard, making a quarter-percent rate cut in September all but certain. The markets are pricing in a larger cut of half-percent and there is a growing consensus that another half point cut will be taken in December. We are not there yet, as such aggressive moves would indicate the Fed sees the economy already in a recession. That prospect would become more of a reality if recession expectations gained more traction, as people would spend less if they feared a layoff. However, such an increase in job insecurity is not supported by recent surveys, which generally report confidence in labor market conditions among households.