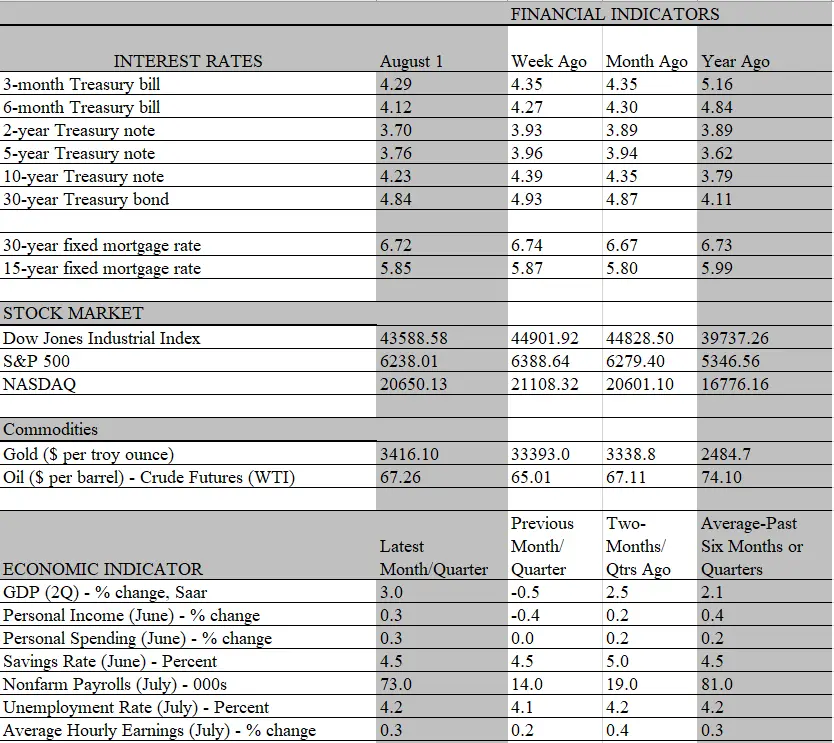

The debate over whether the economy is responding more to tariffs or interest rates will undoubtedly heat up, as the week’s busy calendar of data only added fuel to the fire. One thing is clear: following Friday’s jobs report, the financial markets dramatically repriced the odds of a rate cut in September, giving it more than an 80 percent shot now compared to about 30-40 percent immediately after the Fed policy meeting on Wednesday. Despite the dissent by two Fed governors – the most since 1993 – of the FOMC’s decision to keep rates unchanged at the meeting, market sentiment broadly coalesced around the view that the Fed would stick to its guns and not make a move until the risk of a weaker job market outweighed the risk of higher inflation. The balance of risks shifted markedly following the surprisingly weak jobs report on Friday.

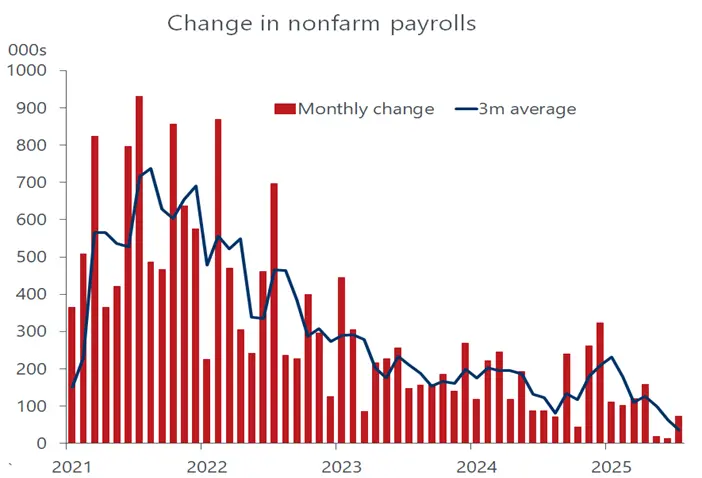

To be sure, it would be premature to say conclusively that the Fed is ready to throw in the towel. The biggest downside surprise in the report was the abrupt downshift in job creation over the past three months. The 73 thousand increase in payrolls in July was only slightly below expectations but the huge downward revisions for the previous two months – slicing 258 thousand from the original payroll estimate for May and June – is what caught the eye of rate-cutting advocates. The result is that the economy only generated 35 thousand jobs per month from May through July, the slowest three-month pace since June 2020, when the economy was just emerging from the pandemic recession. Before that, you would have to go back to 2010 to find a weaker stretch of job growth.

The picture looks a bit less dire when government workers are excluded, as private payrolls increased by 85 thousand in July and 52 thousand on average over the past three months. But the slowdown is just as dramatic and would be considerably deeper if not for another sturdy 73 thousand gain in health and social services payrolls, which accounted for all the increase in the private sector and then some. Indeed, take out the job gains in this mostly noncyclical sector that reflects an aging population, and private sector job growth would show a decline over the past three months. We note, moreover, that manufacturing jobs, which tariffs are designed to bolster, fell for the third consecutive month in July, a stretch of losses not seen since the pandemic.

One reason Powell may not be ready to surrender to the rate-cutting crowd is that he views the slowdown in payrolls as being heavily influenced by the sharp drop in immigration. That, in turn, is reducing the supply of labor and, hence, the number of new jobs needed to keep the unemployment rate from increasing. That rate did edge up from 4.1 percent to 4.2 percent in July but remains historically low. By this measure, the labor market is still holding up, reflecting a rough balance between the demand for and supply of workers. That perception is supported by the more detailed breakdown of labor conditions provided in the JOLTs report. The latest report for June shows that hiring is sluggish but so too are layoffs, and there are as many job openings as unemployed workers.

However, viewed as a static metric, the equilibrium indicated by both the JOLTs data and the unemployment rate overstates the positive implications for the economy. While the demand and supply of workers may be declining at the same pace, keeping the unemployment rate steady, the shrinkage is also removing purchasing power from the economy that would have been generated by a faster growth in balanced employment. Simply put, a low unemployment rate forged by a lowered breakeven rate of job growth points to weaker growth in aggregate income and spending.

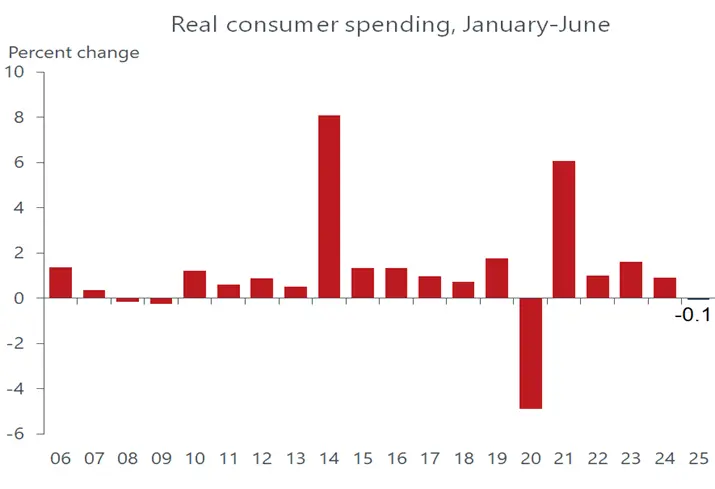

That, together with the downward revisions to payrolls in previous months may explain the sluggishness in consumer spending over the first half of the year. The tariff-induced gyrations in monthly consumer spending data have obscured a trend that strongly reflects that behavior. From the beginning of the year through June, real personal consumption has been virtually flat, notching a small 0.1 percent decline. Such a lengthy period of stagnant spending is rare outside of a recession and has not occurred since the six-month span encompassing the 2020 pandemic. Unsurprisingly, the previous episode took place during the tail-end of the 2007-2009 Great Recession.

That said, there are reasons to believe that consumers are not about to zip up their wallets going forward. For one, workers are getting decent wage increases for staying on the job. Average hourly earnings increased by a steady-as-you go 0.3 percent in July, nudging the increase over the past year up to 3.9 percent from 3.8 percent in June. That’s comfortably outpacing the increase in inflation, supporting the purchasing power of job holders. For another, households will be getting tax breaks and refunds in 2026 that should pad their bank accounts, even as other fiscal measures will incentivize employers to keep hiring and spending.

No doubt, following the latest jobs report, the Fed will be coming under more pressure to cut rates sooner rather than later. The odds of a move in September have increased but is far from a slam dunk in our view. As noted, the unemployment rate, which Powell deems important, remains low, wages are rising at a healthy clip and inflation is still stubbornly above the 2 percent target. There is another employment report scheduled before the September FOMC meeting, which may see a bounce back in payrolls. Conversely, if that report features downward revisions like the latest one, the Fed may well capitulate and pull the rate-cutting trigger.